Jerry Garcia: "There’s a thing about playing stoned without having pressure to play competently... People pay a lot of money to see us, so it becomes a matter of professionalism. You don’t want to deliver somebody a clunker just because you’re too high”

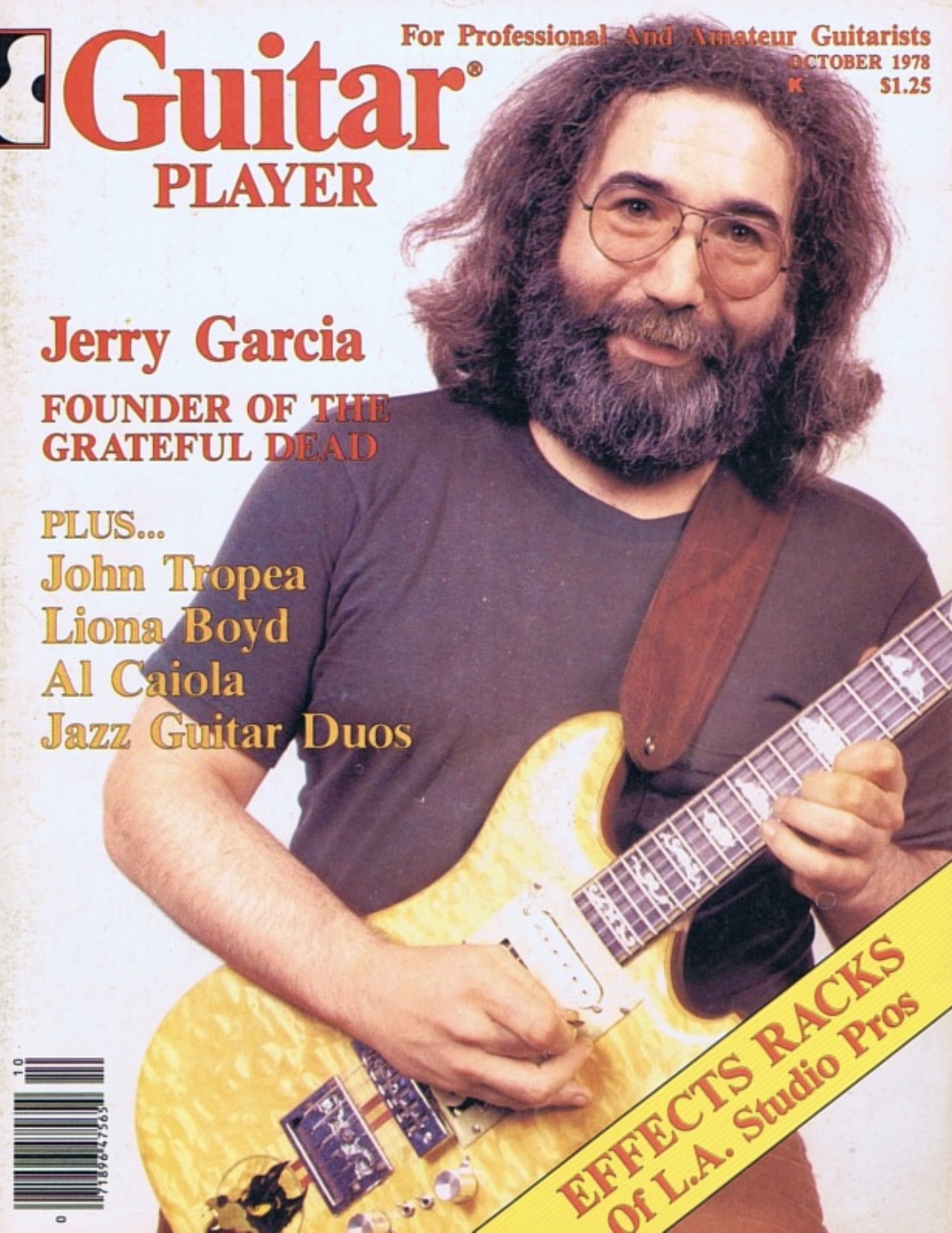

In this 1978 chat with GP, the late Grateful Dead legend discusses why he chose to not include anything shorter than a half-note in a solo for a year, and reveals how the five-string banjo informed his unique six-string approach

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The following interview originally appeared in the October 1978 issue of Guitar Player.

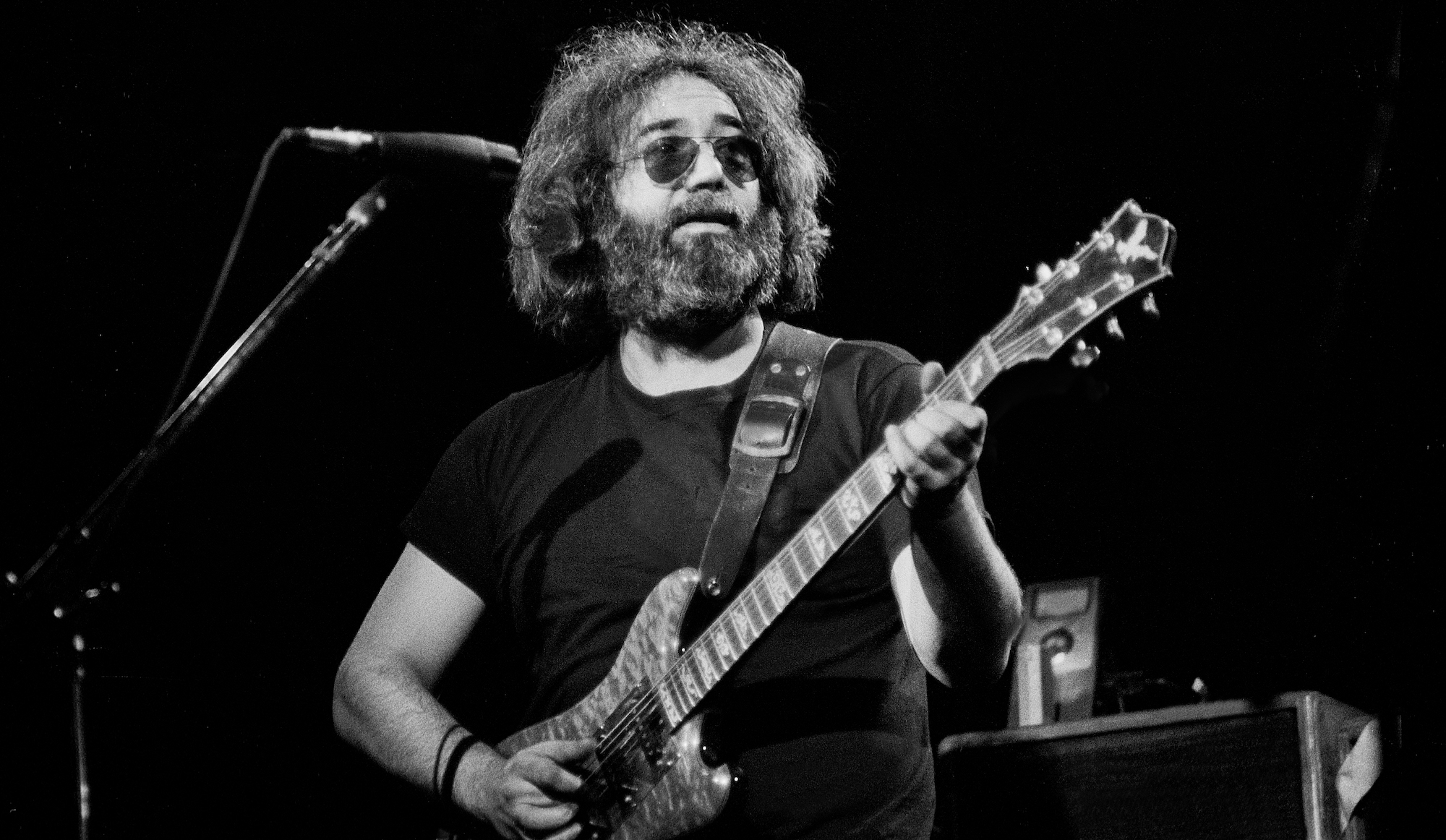

Jerry Garcia and the Grateful Dead have become cultural institutions, though they never planned it that way. Other bands have achieved a similar status, but for different reasons – unlike the major rock attractions who are idolized from afar, the Dead are seen up close, enjoyed, and respected. They were patriarchs of San Francisco’s psychedelic colony of the 1960s, city fathers in a community of crazies.

As perceived in the general press, Garcia and company were the hippie band, playing music for getting stoned, seeing God, dancing, singing, blowing bubbles, mellowing out, or whatever – good-time music without rock-star pretensions. But the Grateful Dead were more than that, and they have produced an extensive catalog of music that transcends the experiences of late-'60s San Francisco.

Today, without hit singles, they remain heroes to their confederacy of loyal fans, or Deadheads.

Looking back, the Dead’s popularity marked a change in popular music. By mainstream commercial criteria, they should have failed. They lacked a charismatic central figure, did not pursue any of the tried and true Top 40 formulas, and did not wear spiffy outfits. They weren’t cute. They didn’t aspire to be chart busters or darlings of the mass media, and they weren’t – they couldn’t have been.

To most promoters, producers, and disc jockeys, the aggregation of San Francisco musicians were nothing more than the noisiest cage in a menagerie of freaks.

The Dead were and are a part of their brotherhood of fans. More than a decade ago, instead of seeking the isolation and celebrity of big-bucks show biz, they gave free concerts. Their go-with-the-flow approach to live performing involved half-hour tuneups, long breaks between songs, marathon concerts, an eventual 23 tons of privately owned equipment, and a lesser amount of drugs.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

These sometimes-impromptu events were promoted by word of mouth or by flower children with rainbow clothes and pinwheel eyes, passing out handbills, perhaps balloons, and sometimes LSD – which was legal until August 1966. Concert posters with kaleidoscopic, highly stylized artwork were tacked up in head shops and on telephone poles.

The do-your-own-thing philosophy of the Grateful Dead should not be mistaken for a lack of seriousness – the Dead were simply serious about doing their own thing. The commitment to their own codes, sometimes interpreted as anarchy by straight record industry execs, provided the band with enormous staying power.

By succeeding on their own terms, Jerry Garcia’s band helped change the 1960s fan/artist relationship and perception from a hopelessly distant, sometimes hysterical worship identification to something born of shared experience.

Previously you’ve said that you seem to go through cyclic learning stages. What causes that to happen?

“I think it’s something that happens to every guitar player as he keeps on playing through the years. You’re struggling to learn a whole body of material, and you finally learn it and can play it expertly, and then you get bored. It becomes a 'now what?' situation. You’re struggling to obtain ground and you reach a plateau, and then your boredom finally drives you to develop to new levels.

“I think that’s a healthy and normal thing. I seem to go through it about once every year and a half or two years pretty regularly. That’s pretty much how my metabolism seems to work. I think of myself really as a guitar student as much as a player or performer, because there’s so much being developed and so much that’s already been done that I’ll never learn it all.”

What kind of things do you do during these stages?

“First, I go out and buy all the new guitar method books that have come out since the last time and read through them and try out ideas and exercises. I find it really helpful to see somebody else’s handle on it, because it’s possible they can show me new ways of looking at the instrument or music that I hadn’t considered before. The state of guitar education today is incredible compared to just 15 years ago. You can learn an astounding amount from just reading books that are available today.

“I’m working very hard now. I’m working hard on things that I haven’t worked hard on before. I have certain exercises that I do, but it’s more like working out little bits and pieces of unfinished ideas.

“A lot of it is just free playing, exploring for places where all of a sudden something is vague or awkward like suddenly finding yourself in a position that’s odd in relation to the key you’re playing in. Or, for example, you’re doing a run that’s going down scale intervals, and you’re on, like, the top E string, and you’re ending on one part of the passage on your first finger and then jumping a position and starting the next part with your little finger and moving down. That’s a difficult thing to do on the guitar.”

How do you learn to master that kind of passage?

“I’ll just keep going over it until it’s smooth, and then it starts to turn up in other places. Anything you work at technically always turns out to have unexpected rewards. You realize later, not only is this convenient for me to make a very full, long run, but it also gets me conveniently from position A to B to C. You start to really see interconnections.”

How is your picture of the fingerboard developing?

“Finally the complete pattern of the fingerboard is becoming more apparent. I’m forcing it into shape in my own psyche, in my own way of seeing and feeling. I’m spending seven or eight hours a day with it. I’m trying to rebuild myself, I feel like it’s time for me to do that in my playing. I don’t know whether it will amount to anything, but in six months I’ll know. I’m sort of in a two-year plan right now – the first pause of the next level.”

The more you play, the more you notice it if you miss a day. But then there’s also the thing that, if you’re away from the guitar for two or three days, sometimes you can come back with something else

When you’re not going through these intense learning periods, how much time do you usually spend with a guitar?

“It depends on the schedule. When I’m on the road it’s a lot more, but when I’m home I’d say I spend no less than an average of two hours a day at the absolute worst. That’s, like, really screwing around.

“I think four hours is more normal for me. on the road it goes up to about six, including the show. I lose my edge in a day if I don’t stay on top of it constantly. Anything more than two days and it’s like being a cripple. And the more you play, the more you notice it if you miss a day. But then there’s also the thing that, if you’re away from the guitar for two or three days, sometimes you can come back with something else.

“Now, that’s not one of those things you can depend on, but sometimes it does happen just in the flow. You come back and you have a little more of something. I don’t know what – confidence, new ideas, or something.”

What do you see as your major limitation?

“A lack of an early musical education. I’ve been able to compensate for it some, but having an early education means that a lot of things become reflexive, automatic. Now, sometimes that can perpetuate bad habits on a technical level, but in terms of sight-reading and the like, I wish I had started earlier.

“I’m not unhappy with my progress, but that’s the one thing. As it is, I’m glad to have been able to develop an intuitive approach to music, and I can see that there could be disadvantages to having a completely schooled approach. Sometimes that blocks out the intuition; there are people with great technique who have nothing to say.”

Most guitar players I’ve noticed seem to use a flat fingering. I’ve somehow trained myself to come straight down on top of the string

How did your early process of music education work?

“My first orientation was learning from my ear. So I learned mostly from records – Freddie King and B.B. King extensively – and, you know, everybody else. That was my first exposure, mostly because the Bay Area didn’t have that many guitar players back when I started playing, and there really wasn’t a lot of local information, or at least I wasn’t able to uncover it.

“For me, I would describe my own learning process as wasting a lot of time. I did it the hardest way possible, or it seems that way now. I had to spend a lot of time unlearning things – bad habits and so forth. I think I went through as many of these unlearning cycles as I could. It was around 1972 or ‘73 when I finally unlearned all the things that had hung me up to that point.”

Like what, specifically?

“Oh, like playing out of preference to certain positions – like tending to think along certain positions because they were more available to my hand, rather than for musical reasons.

“It became a serious problem for me to correct onstage. I think that’s an easy trap to fall into – doing things that are merely easiest for you and are within your immediate grasp with the excitement of playing on stage. And other things I would describe as rhythmic and idea habits in addition to technical habits – having a more or less limited kind of vocabulary and tending to depend on my ability to exploit it rather than developing a greater vocabulary.

“I’ve been through a lot of things like, for example, deciding never to play anything shorter than a half-note during a solo for a year in order to cut down the busy-ness. I get tired of busy stuff, and I decide that I want to exploit the single-note capability and the tone of the guitar, so for a period I play really slow leads regardless of the rhythmic path. After awhile I get tired of doing that and start working on developing speed.”

Could you discuss your approach to fingering?

“I think it has something to do with my early five-string banjo playing. Most guitar players I’ve noticed seem to use a flat fingering. I’ve somehow trained myself to come straight down on top of the string. I play mostly on the tips of my fingers, so the high action doesn’t get in my way at all. I’m not pulling other strings along with it and so forth.”

Do you use the little finger on your left hand much?

“Yes. Early on, I was lucky enough to have someone point out the usefulness of that finger. As a result it is one of my stronger fingers, and I prefer to use it even more than my ring finger.

“That’s always made me different from most rock guitarists that I know – even the really good ones. I think in rock and roll a lot of guitar players favor something that lets them use the ring finger for greater articulation and vibrato effects. For me, I’ve got to be able to do it with every finger. I find it ridiculous to have to close all my ideas on my ring finger just so I can get a vibrato. That eliminates a lot of possibilities automatically.”

How do you achieve your vibrato?

“Well, I have about four or five different families of vibrato. Some of them are unsupported; that is to say, nothing is touching the guitar but my finger on the string. Other methods are supported, and I just move the finger for the sound. Sometimes I also use wrist motion, and other times I’ll move my whole arm. I also use horizontal and lateral motion for different sounds and speed.

“Each has its own separate sound, and it depends on what I’m going after and which finger I’m leading with. For example, if you’re playing the blues, it’s generally appropriate to use a slow vibrato. Generally speaking, I tend to be style-conscious in terms of wanting a song to sound like the world it comes from.”

If the band is playing in 7/4 time, I might play in 4/4. When you do that sort of thing, you begin to notice certain ways in which the two rhythms synchronize over a long period of time

Do you play many notes by hammering-on and pulling-off?

“Generally, I like to pick every note, but I do tend to pull-off, say, a real fast triplet on things that are closing up-intervals that are heading up the scale. I do it almost without thinking about it. I almost never pull off just one note. I seldom hammer on, because it seems to have a certain inexactitude for me. I think that was a decision I made while playing the banjo.

“My preference is for the well-spoken tone, and I think coming straight down on the strings with high knuckles makes it. So my little groups of pull-offs are really well-articulated; it’s something I worked on a lot.”

How do you approach right-hand technique?

“Generally I use a Fender extra heavy flatpick, which I sometimes palm when using my fingers. The way I hold the pick is a bit strange, I guess. I don’t hold it in the standard way but more like you hold a pencil. I think Howard Roberts describes it as the scalpel technique. The motion is basically generated from the thumb and first finger rather than say, the wrist or elbow. But I use all different kinds of motion, depending on whether I am doing single-string stuff or chords.”

Could you discuss your distinctive approach to accenting?

“Again, a certain amount of it is related to banjo playing, where you have problem-solving continually going on. There are three fingers moving more or less constantly, and you have to change the melodic weight from any one finger to any other finger. What that really involves is rhythmic changes. So, for me, it’s always been interesting to have little surprises like, for instance, accenting all the off-beats for a bar.

“There’s also the constant playing in odd times with the Grateful Dead that contributes to that. For instance, if the band is playing in 7/4 time, I might play in 4/4. When you do that sort of thing, you begin to notice certain ways in which the two rhythms synchronize over a long period of time.

“Thinking in these long lengths, you automatically start to develop rhythmic ideas that have a way of interconnecting. If you’re in the right kind of rhythmic context, then you have the option of being able to continually reevaluate your position in time. For me, it then becomes a thing of syncopations based on other syncopations.

“For example, I like to start an idea when the music is in flow on a sixteenth-note triplet off of four. So that’s, like, intensely syncopated on its own, and if I start my phrase there, it’s like constructing one sentence off of another one before the first sentence is completed. That sort of linguistic analogy is something I’m very attracted to.”

Could you talk about your process of composition?

“I usually compose on the piano. The melody usually comes first, and then the accompaniment. Most often I’ll record it on a cassette, though there are certain things that I feel must be written out, or I’ll definitely lose them.

“I can play things on a piano and have no idea what they really are unless I analyze them. I don’t play piano that well, but it’s possible to come up with a six-note chord that could be anything when I hear it on a tape. So sometimes I find it helpful to keep track of how I arrive at an idea, though I do find that if the idea has enough weight it sticks with me, and I rediscover it again later. I’m a lazy writer, not at all diligent.”

How do you and Robert Hunter work together on songs?

“It works just about every way. Sometimes I have a melody that must have a certain kind of phrasing, and it becomes a matter of discipline for him. I get down to very specific terms in telling him what musical qualities a lyric must have – at this point I want a vowel, at this point a percussive sound. Then other times he gives me a sheaf of lyrics, and I’ll go through them and find ones that appeal to me and start to work on them. Then sometimes when we’re working together to polish things up, a whole new idea will emerge, and we’ll go with that.

“We trust each other. He trusts my ability as an editor; and I edit extensively – sometimes it drives him nuts – but we work together pretty well. It’s been a long working relationship.”

People have to pay a lot of money to see us, so it becomes a matter of professionalism. You don’t want to deliver somebody a clunker just because you’re too high

What process do you go through for building solos?

“The way I start is to learn the literal melody of the tune. Then I construct solos as though I’m either playing with it or against it. That’s a pretty loose description, obviously, because there are a lot of other factors involved. Later on, I start to see other kinds of connections, but one of my first processes is to learn the literal melody in any position.

“I am very attracted to melody. A song with a beautiful melody can just knock me off my feet, but the greatest changes on Earth don’t mean anything to me if they don’t have a great melody tying them together in some sense.”

Have you noticed any particular logic to the way the Dead have progressed through the years?

“No, and that’s one of the things that I constantly find interesting about the band. Each one develops in a different way and with a different sense of his own development. All of a sudden there’s somebody with a whole bunch of ideas that you haven’t stumbled on and might never have. That’s the fun part of playing with other people and exposing yourself to different musicians. You find all these possible ways to grow.

“The Grateful Dead have never developed as a group. I mean, we’ve developed as a group in a certain kind of large sense, but everybody’s individual development has that thing of being surprising, interesting, and entertaining. That’s one of the things that keeps the Dead interesting to be involved in.”

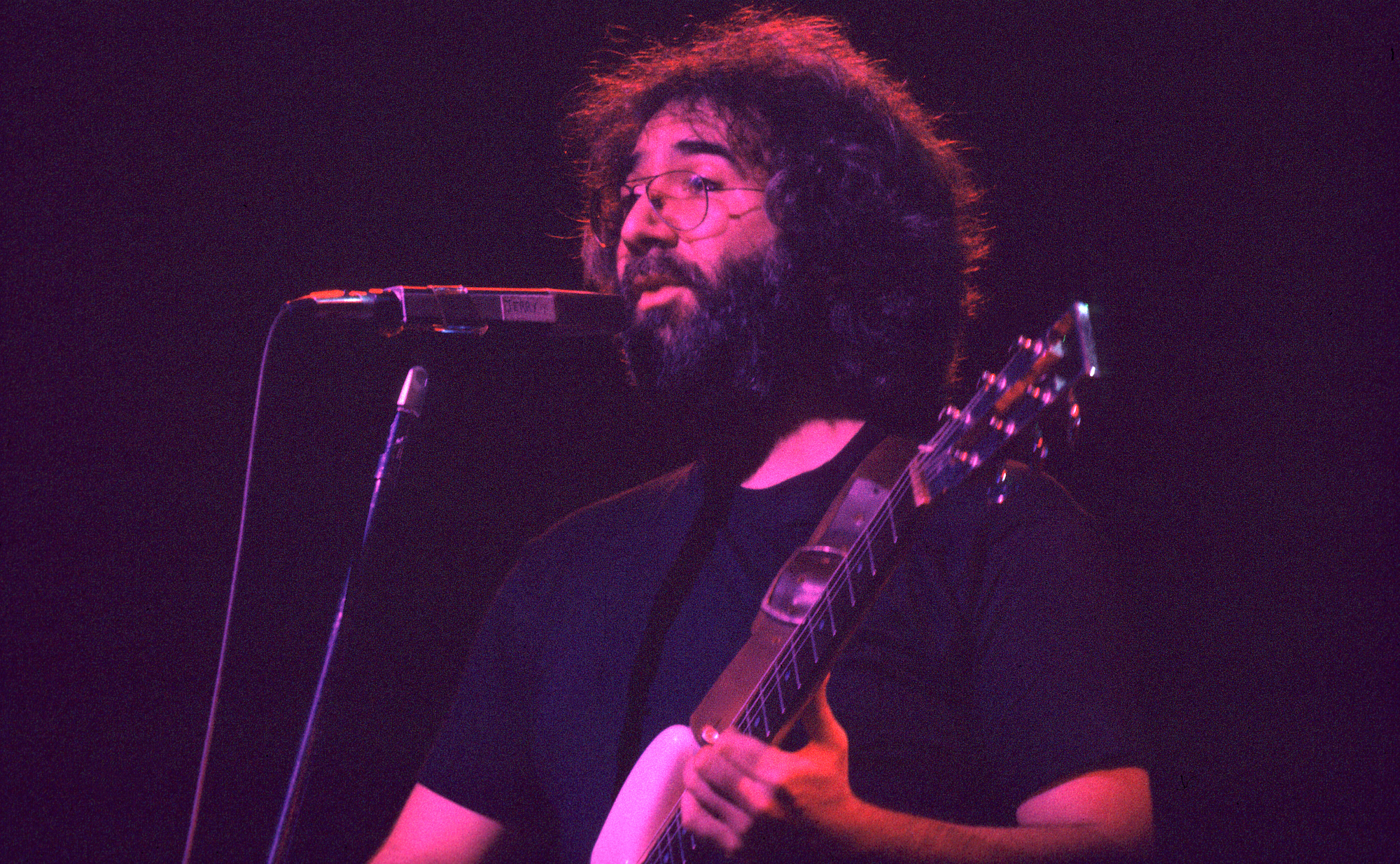

Could you say a few words about any merits or disadvantages of playing stoned?

“There’s a thing about playing stoned without having pressure on you to play competently. If you have the space in your life where you can be high and play and not be in a critical situation, you can learn a lot of interesting things about yourself and your relation to the instrument and music. We were lucky enough to have an uncritical situation, so it wasn’t like a test of how stoned we could be and still be competent – we weren’t concerned with being competent. We were more concerned with being high at the time.

“The biggest single problem from a practical point of view is that, obviously, your perception of time gets all weird. Now, that can be interesting, but I try to avoid extremes of any sort, because you have the fundamental problems of playing in tune and playing with everybody else. People have to pay a lot of money to see us, so it becomes a matter of professionalism. You don’t want to deliver somebody a clunker just because you’re too high.”

What do you have to say about the state of guitar playing in general?

“There are more good guitar players alive today than have ever existed. I welcome it. It’s been a long time getting here, the legitimizing of the electric guitar. Everybody has something to say. I really feel that you can’t avoid finding your own voice if you keep playing. You have a voice, whether you recognize it or not.”