All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Recently, a proliferation of clips has appeared on YouTube in which young music fans document their reactions to hearing the music of Grand Funk Railroad for the first time.

Their faces are braced with stunned, slack-jawed amazement as they listen. When the music stops and the talking begins, their assessments of the band are typically along the lines of, “Damn, those guys can really jam!” and “What did I just hear?!” Asked if he’s familiar with the videos, Mark Farner lets out a robust laugh. “Hell yeah, I’ve seen them!” the former Grand Funk Railroad guitarist exclaims.

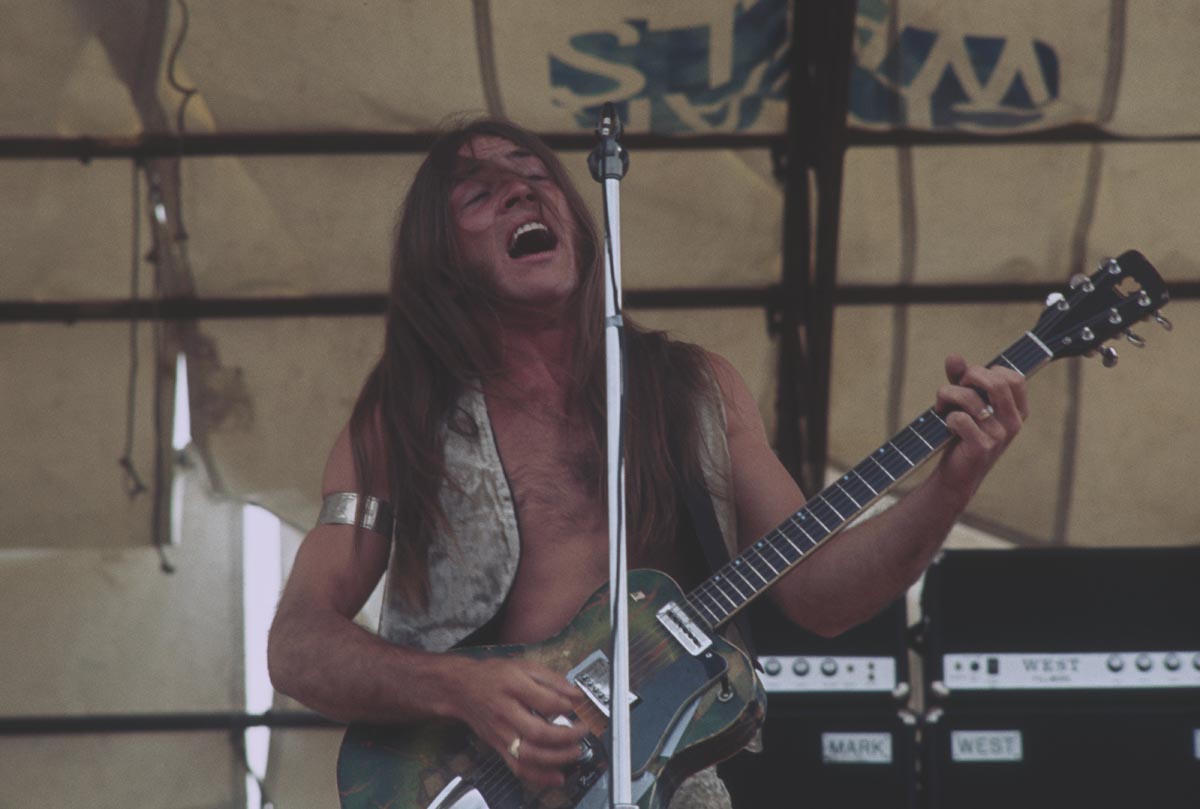

“My friends send me those clips, and I just love watching them. I think it’s so cool seeing these young guys getting off to the music we made 50 years ago. What touched people’s hearts back then still moves them today. We were fierce. We were big and loud, like we were busting out of the chute. And I was riding the bull, man. You can’t fake that kind of excitement. It’s either real or it’s not.”

We were the people’s band. We sold out Shea Stadium faster than the Beatles, and that was before we had Number One singles on AM radio

He chuckles, then adds nostalgically, “It sure was a fun time.” For the better part of their career, which lasted from 1969 to 1976, the Flint, Michigan–based Grand Funk Railroad specialized in high-energy, meat-and-potatoes, blues-based hard rock.

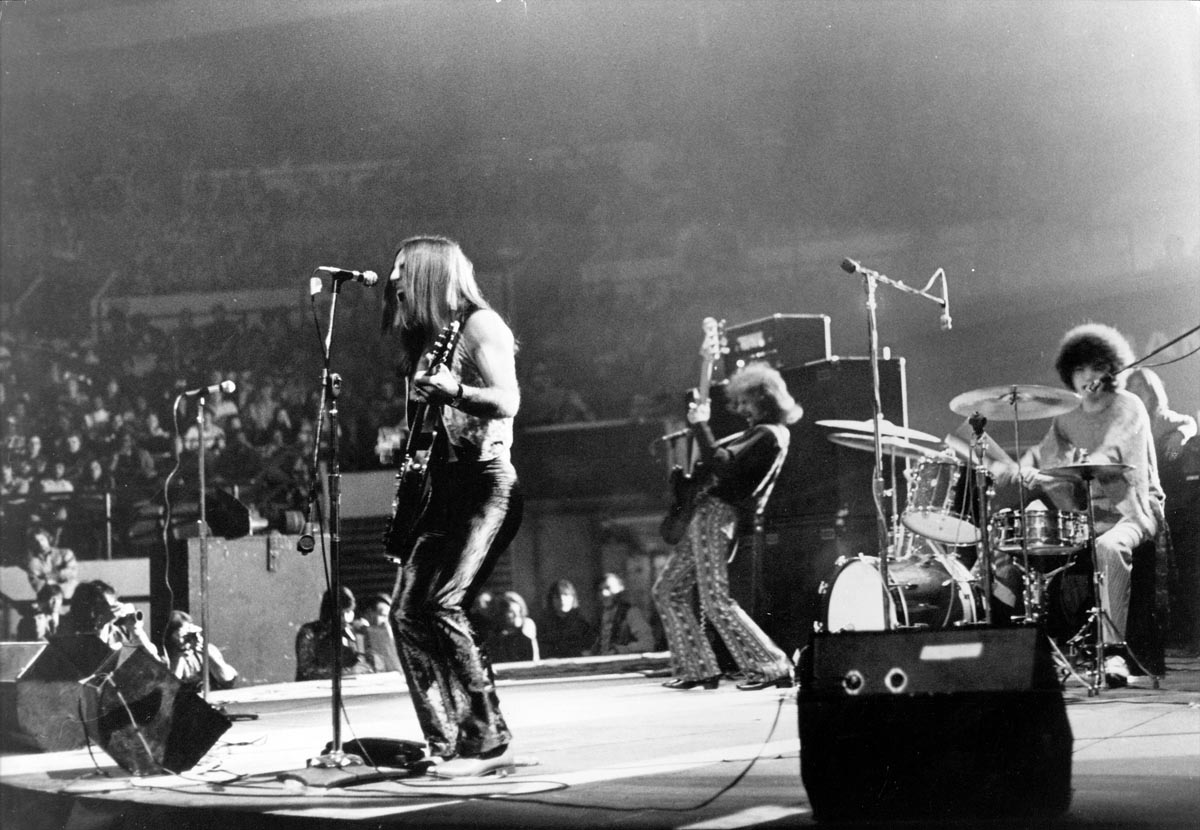

Consisting originally of guitarist and lead vocalist Farner, drummer and occasional lead singer Don Brewer, and bassist Mel Schacher, Grand Funk Railroad formed after the breakup of a local outfit called Terry Knight & the Pack. The trio barnstormed its way through Michigan, performing on bills with fellow Midwestern acts like the Stooges, the MC5, and the Amboy Dukes.

Guided by Terry Knight, who retired from the stage to act as the band’s manager, Grand Funk Railroad soon exploded nationally, issuing a string of Platinum albums that included FM radio hits like “Mr. Limousine Driver,” “Inside Looking Out,” and “Mean Mistreater.” With the release of 1970’s Closer to Home, which included the epic hit song “I’m Your Captain/Closer to Home,” the group was all but unstoppable.

“We were the people’s band,” Farner says. “We sold out Shea Stadium faster than the Beatles, and that was before we had Number One singles on AM radio. We were honest in how we played, and we were honest in what we sang about. It was the Vietnam era, and I was writing songs like ‘People, Let’s Stop the War.’ That song is as relevant today as it was back then. That kind of message resounds with people.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

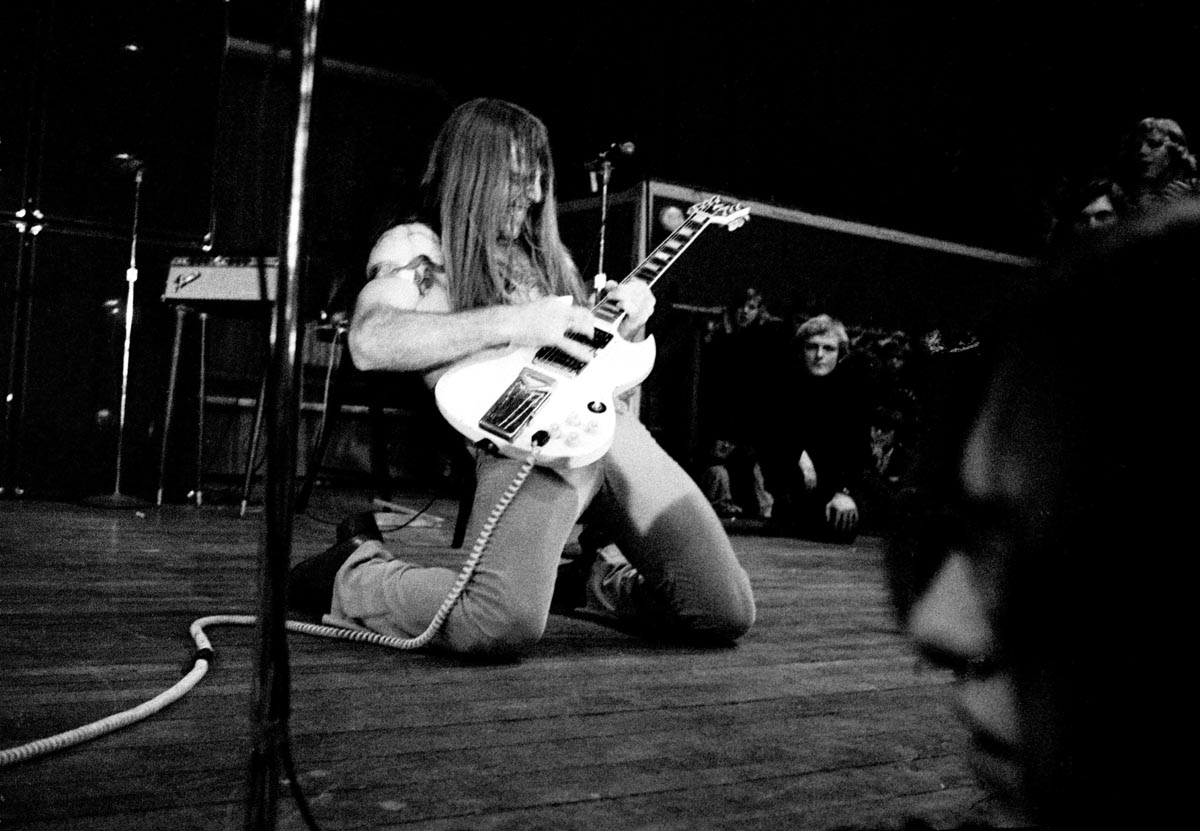

Much of Grand Funk Railroad’s raucous sound was driven by Farner’s unbridled guitar playing, an exuberant mix of tight, power-chord rhythms and fuzzed-out, throat-grabbing leads.

“I didn’t play nearly as fast as the other guitarists back then,” he says. “My whole approach was, How can I reach the people in the back row with my guitar? I wanted to accentuate the visual image of me onstage with what I played. So if it was simple, but it got the point across, that’s what I did.” He thinks, then adds, “That’s what I still try to do now, though I think I’m a little more mature with the notes I pick.”

I didn’t play nearly as fast as the other guitarists back then. My whole approach was, How can I reach the people in the back row with my guitar?

During the last few years of their ’70s run, Grand Funk Railroad (later known simply as Grand Funk) became a quartet with the addition of keyboardist Craig Frost and defanged their sledgehammer sound, resulting in AM-friendly smashes like “We’re an American Band” and a cover of Little Eva’s “The Loco-Motion,” both produced by Todd Rundgren.

While such moves attracted a new legion of fans, the band’s original admirers grew disgruntled. When the group couldn’t replicate its chart success, it flamed out following the release of 1976’s Frank Zappa–produced Good Singin’, Good Playin’.

“A lot of people didn’t like us being so poppy,” says Farner, who these days performs with Mark Farner’s American Band. “And I was right there, too. I voted against getting a keyboard player. I wanted to keep the emphasis on being a guitar band. It’s sad how things went down, but I’m thankful for all we achieved. We hit heights nobody could have imagined. How many people get to say that?”

You’ve said the original trio was patterned after Cream. How did you distill that sound into something of your own?

We took that British influence, but we weren’t literally trying to be Cream. Our main influence was R&B. It’s what brought us to the dance floor. That’s what we wanted to do; that’s what I wanted to do as a guitarist. It wasn’t about playing long solos; it was about getting people to dance.

I was attracted to rhythm, and I think the guys in Cream were too. They were soulful. We were soulful. When we first started playing gigs, I’d look out and see that half the audience was African-American.

Pete Townshend took it way outside the norm, and that really rubbed off on me. I always liked messing around with volume.

You’ve cited Hendrix, Clapton, and Beck as your biggest guitar influences. Was there anybody before those guys who made a strong impression on you?

You can put Rick Derringer in there, too. I’ve always admired his style. Before him, there was James Burton, who played for Ricky Nelson and Elvis. I would listen to those leads and think, How does he do that?

I was just a young guitar player with my Kay acoustic, and I could barely play that thing. The strings were so far off the neck, you could use them to shoot an arrow. And, of course, I dug the early rock and roll – Bill Haley and “Rock Around the Clock.” That was the stuff that got me going.

What about Pete Townshend? I have to think that he rubbed off on you a little.

Oh, sure. He was a very solid player; lots of energy and well-crafted parts. I especially liked what he did by cranking up the volume. He took it way outside the norm, and that really rubbed off on me. I always liked messing around with volume.

Were you a natural on the guitar, or did you really have to woodshed and work at it to become good?

I had three lessons, and in the first lesson I was taught to keep my fingernails trimmed so they didn’t touch the fingerboard. I would’ve had more lessons, but my teacher shot himself in the foot with a 12-gauge while he was hunting. He was all right, but he couldn’t teach guitar anymore.

After that, I taught myself. I watched guys in high school bands and picked up the chords they were using. Once I got enough chords down, I was off doing it on my own. I loved playing guitar. I’d go to sleep with it on top of me. When I woke up, I’d think, Well, I’d better put it back in the case, but I never did. I always wanted the guitar around.

The Kingsmen were using Sunn amps, and they sounded so badass. So we went, 'Wow, man, we need some Sunn amps!'

When Grand Funk were just starting out, how did you go about putting together your sound with respect to your guitar and gear?

We had gone to see the Kingsmen – they had that song “Louie Louie.” They were using Sunn amps, and they sounded so badass. So we went, “Wow, man, we need some Sunn amps!”

But in our quest for them, we found Dave West from Flint, Michigan, and he was building his own amps that were just as big and loud as Sunn amps. They had big tubes and big cabinets.

I actually worked in his factory for a time, soldering circuit boards and putting things together. So when Grand Funk took off, I said, “We’ve got to use West amps. He’s from Flint, and we’re taking him with us.”

Aside from their power and size, was there something in particular about the tone of West amps that worked for you?

As I came to discover, Dave West had inadvertently wired something backward in his circuitry. He was doing mods to make his 60-watt amps 100 watts, and then he went to 200 watts by accident. Something was all backward, and when he went to change it, I said, “No way, dude! You’re going to screw it up. Just leave it the way it is.” I really loved the sound of it with my Messenger guitar.

That would be your ’67 Musicraft Messenger. Where did you get that?

One of the reps for Sunn said, “You’ve got to try one of these new guitars. They’ve got aluminum necks, and you can play up to the last fret without running into the body.” I tried one and liked it. The neck dimension was the same from one end to the other. I paid the guitar off for $25 per week.

The thing was heavy to hold. Because the neck was aluminum and the body was hollow, it was off balance. If you took your hands off the guitar, the neck sank to the floor. I remember I stuffed the f-holes with foam and put masking tape on them. Then I did a psychedelic paint job on the guitar so it would glow in the dark.

You also used Micro-Frets guitars: a Signature and a Spacetone. Where did those come from?

I was playing [Ernie Ball] Slinky strings, but I noticed that I had a tendency to go sharp, even just playing an E chord. The Micro-Frets guitars stayed in tune. I played one and said, “These are gonna work!” I went to their factory in Nashville and struck up a deal with them, and they gave me some guitars to play. You had to work the truss rod a bit to straighten out their necks, but other than that they were great.

Around this time, you also used a ’61 Les Paul SG Custom.

I got that from Stevie Marriott. He sold it to me for $200. We had played with Humble Pie in the U.K., and we told them, “You guys need to come to America. You can open for us and we’ll give you a big audience.”

Steve told me, “I’ve got this SG that I think you’ll really like. I’ll bring it with me when we come to the States.” And he did. It had been epoxied, because the headstock had snapped on it. But I loved that thing. It was so easy to play and had a nice sound. I ended up giving it to my brother, and I don’t know what he did with it.

Were these guitars and the West amps as good in the studio as onstage?

Definitely. Everything we had onstage was what we used to record with. Of course, I wouldn’t bring all the cabinets into the studio. Half of what I had on stage wasn’t even wired up. I had four cabinets per side that were active, and the others were just for show.

For the first half of the band’s career, you were the main songwriter. Did you feel a lot of pressure?

I didn’t feel any pressure whatsoever. It was flowing, man. The songs happened so fast, I couldn’t stop ’em!

“I’m Your Captain (Closer to Home)” might be your signature song. Did you have any idea when you wrote it that it would be your breakthrough to radio?

I did. I prayed for that song. I remember saying a P.S. in a prayer: “God, would you give me a song that can reach people and touch their hearts?” And I got up in the middle of the night, picked up a legal pad, and, in a half-conscious state, I wrote it down.

When I woke up, I poured my coffee and picked up a Washburn acoustic, and I just started playing that opening lick. I thought, Wow, that’s pretty cool! I remember looking down at this C inversion I was playing, and I thought, Man, I can’t forget this C. I kept playing it till I knew I’d remember it.

Then I grabbed my legal pad and sang the rest of it. It felt good to me, so I took it to rehearsal, and Don and Mel said, “Hey, Farner, that song is a hit, dude!” Because it was way different than anything else we had done. It was there lyrically, and it had that refrain – “I’m getting closer to my home” – going out. [Arranger and trumpet player] Tommy Baker did the orchestrations when we recorded it.

He said to me, “Mark, man, I want that refrain to go on forever. Give me some room for the orchestration.” We must have played it so many times. I remember looking at him like, Should we stop now? And he was just going, “Not yet. Keep playing!”

The story goes that at one point you guys made an overture to Peter Frampton to join the band.

The band discussed it, but we never actually spoke to Peter about it. This was around the time that Craig Frost came into the group as a keyboardist. Don wanted a keyboard player who he could write with. He wanted some of that “mailbox money.” Peter Frampton’s a great player, but we never got past the idea stage with that.

And, of course, you weren’t into the idea of a keyboardist.

I wasn’t. Keyboards are good as long as they’re edgy and fit in a rock-and-roll song. If they’re not edgy, I don’t like ’em. We never got into the progressive thing that was happening back then. We just wanted to stay in the groove.

Rundgren was great – very laid back most of the time. He’d have his feet up on the console, reading a book. He was just kind of a “go for it” guy

Did you plan your solos out, or were they improvised in the studio? Your solo to the song “We’re an American Band” sounds perfectly composed.

They were pretty much spontaneous in the studio. I would have to listen back to them to replicate them onstage. Most of the leads for “We’re an American Band” were improvised.

The only part that wasn’t was when I overdubbed the harmony part in the solo. We were listening back to it in the studio, and I just started singing a harmony line. Todd Rundgren looked at me and said, “You want to put that on there?” So I did.

What was it like working with Rundgren? He’s a pretty capable guitarist himself.

He was great – very laid back most of the time. He’d have his feet up on the console, reading a book. He was just kind of a “go for it” guy. But I remember once when he got really excited. It was on the second record we did with him [Shinin’ On, 1974], when we cut “The Loco-Motion.”

We started playing, and when I did my guitar solo, he came out into the studio, grabbed the tape head of the Echoplex and moved it back and forth. It sounded like the guitar was eating itself. We had a lot of fun with that.

Let’s talk about how the band broke up. Was there a particular day when you realized it was all over?

Sure. It was one day in 1976, when Brewer came into rehearsal late – and he was never late for anything. He walked in and said, “Guys, that’s it. I’m over it. I’ve got to find something more stable to do with my life.” I said, “You’re shitting me.” And he looked at me and said, “No, it’s over, Farner. I’m done.” So I knew it was over then. That was it.

You and Don reunited briefly as Grand Funk Railroad in the early ’80s, after which you went solo again. Nowadays, Don and Mel are leading their own version of the band. Is there any communication between you?

No. I haven’t seen them play, and I’m not interested. They’re a sham band. What they’re doing isn’t Grand Funk, but they don’t tell the unsuspecting fans. They don’t let them know that the original lead singer and the guy that wrote 92 percent of the music isn’t going to be onstage. It’s underhanded.

But me, when I play, I’m taking it to the people. I have it in my mind that these people are here because they like me. They’re on my side to start with, so I try to give them the nostalgia that they’re looking for. I play the songs like they heard them on record.

That’s what I concentrate on. Even with solos, I don’t give ’em any impromptu lead guitar or something that goes on. I’ve seen bands that do that, and it just sucks, man. I give the people what they want.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.