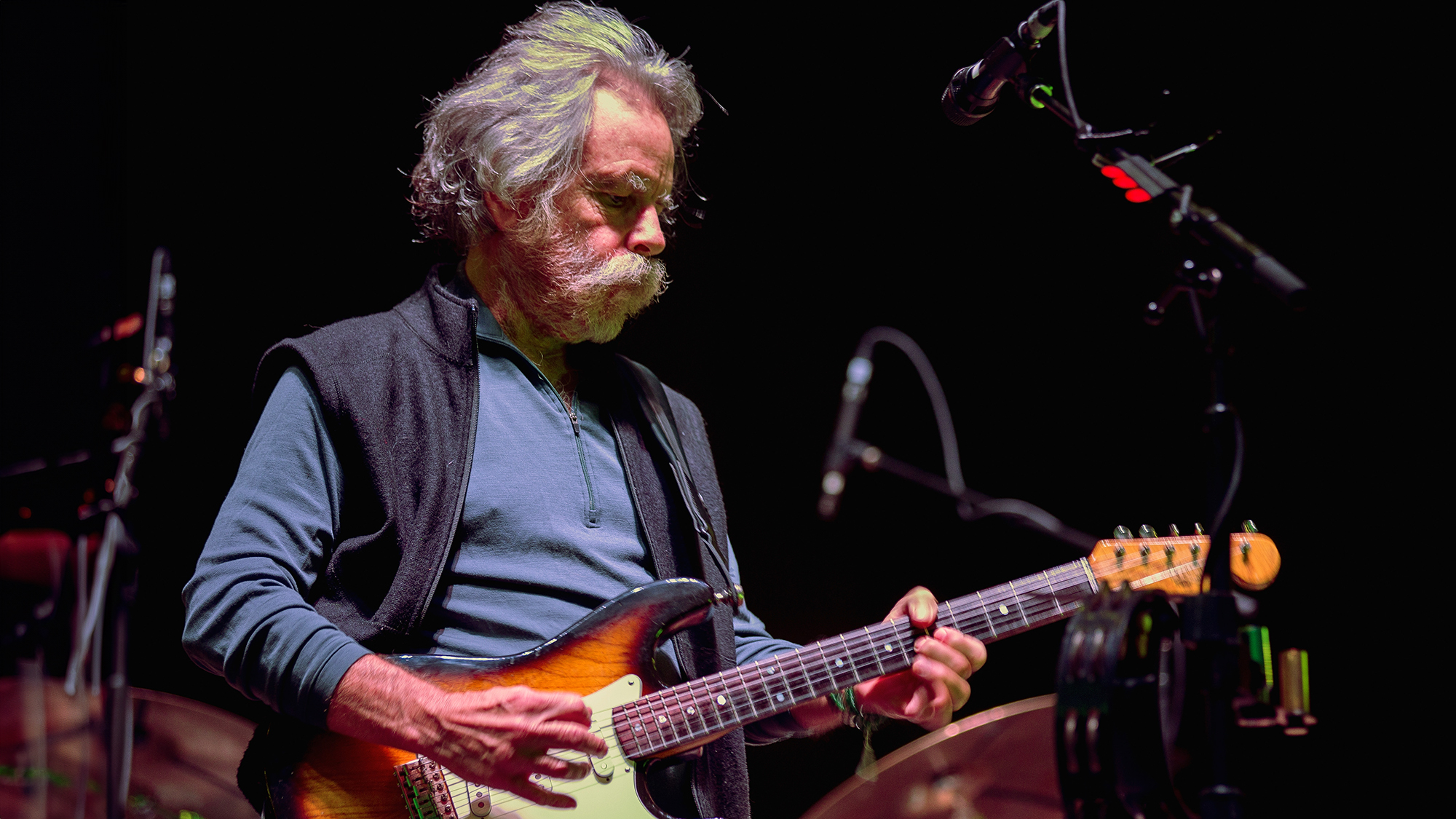

“I told them, ‘You can call the police or do whatever you're going to do to me, but I'm taking it.’” How the Grateful Dead's Bob Weir stole one of his favorite guitars from George Benson

Weir, who died on January 10, had about 100 guitars, but Benson‘s was special

Bob Weir rarely parted ways with his guitars. Over the years he spent as a founding member of the Grateful Dead — and afterward with groups like his jam band Ratdog and Dead & Company — Weir acquired about 100 electric and acoustic models he said in the 2015 documentary, The Other One.

But Weir, who died January 10 at age 78, told Guitar Player in 1998 that he had two favorite guitars in his collection: a Gibson ES-335 from the early '70s (“an old sweetheart”) and an Ibanez George Benson model with an interesting back story.

“I was working with Ibanez on some designs in the mid '70s,” Weir confessed, “and they showed me a new guitar that had just come in from Japan. I played it a bit, and they told me they had made it for George Benson. I told them, ‘No, you didn't. You can call the police or do whatever you're going to do to me, but I'm taking it.’

“It still has Benson's name on it, and I've written so many songs on that guitar. I don't know if George knows that ever happened, and I'd like to apologize to him.”

Weir’s death comes months after he was diagnosed with cancer in the summer of 2025. Although he beat the cancer, he succumbed to underlying lung issues, according to a post on his Instagram page.

A post shared by Bobby Weir (@bobweir)

A photo posted by on

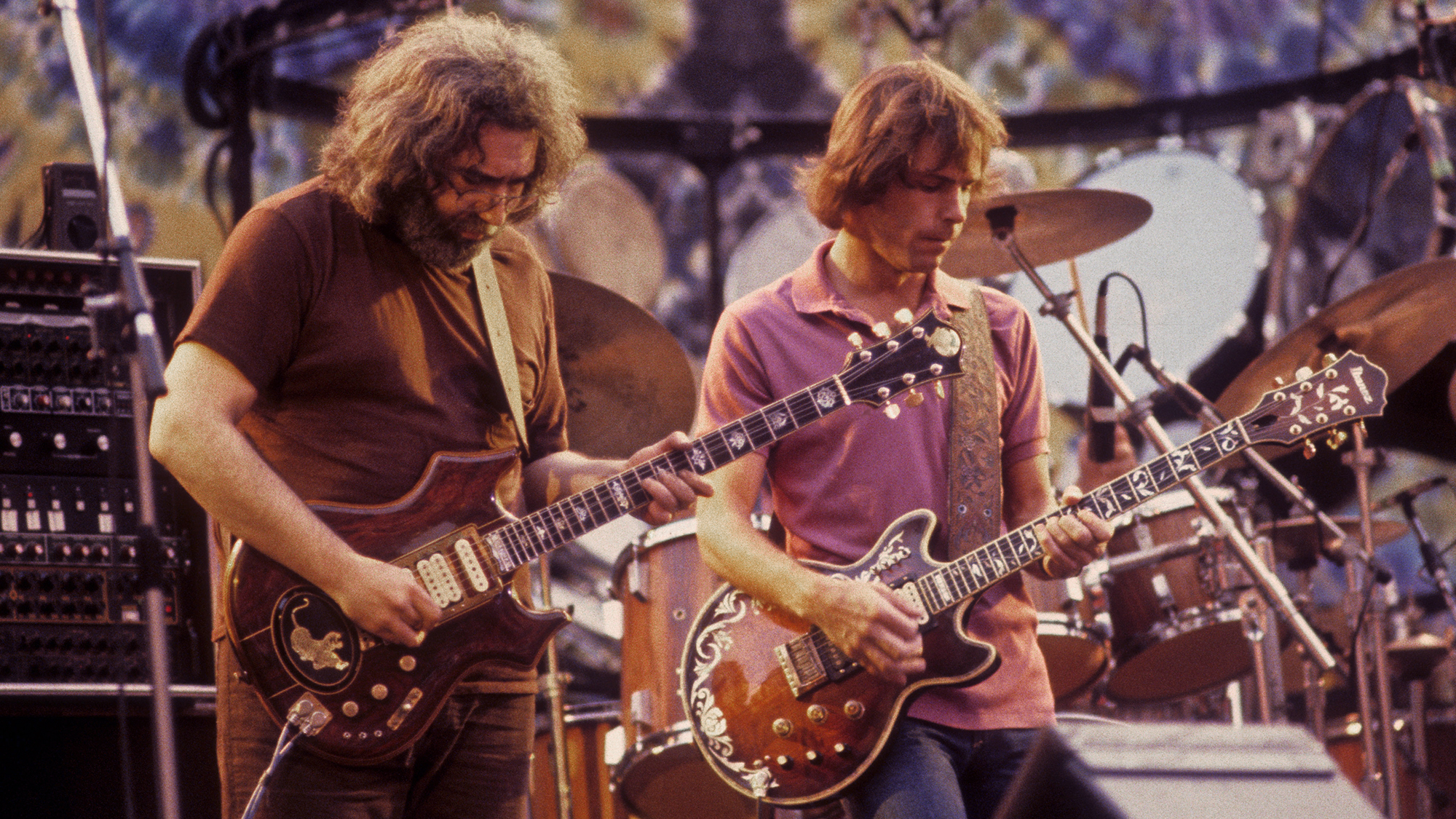

Over his years with the Grateful Dead, Weir established himself as a vital member of the group. No one better articulated Weir’s contributions to the band than Jerry Garcia, who relied on Weir’s innovative chording and steady rhythms as a support for his own virtuoso lead work.

“He's like my left hand,” Garcia told Guitar Player’s Jon Sievert in the October 1978 issue. “We have a long, serious conversation going on musically, and the whole thing is of a complementary nature. We have fun, and we've designed our playing to work against and with each other.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“We have a long, serious conversation going on musically, and the whole thing is of a complementary nature.”

— Jerry Garcia

“His playing, in a way, really puts my playing in the only kind of meaningful context it could enjoy. That's a hard idea to communicate, but any serious analysis of the Dead's music would make it apparent that things are designed really appropriately. There are some passages, some kinds of ideas, that would really throw me if I had to create a harmonic bridge between all the things going on rhythmically with two drums and Phil [Lesh]’s innovative bass style. To solve that kind of problem as he does is extraordinary.”

Jefferson Airplane and Hot Tuna guitarist Jorma Kaukonen spoke glowingly of Weir’s talents in an interview with Guitar Player late last year. He noted how Weir studied with blues guitarist Reverend Gary Davis and came back with an arsenal of remarkable chord shapes.

“Bobby’s a freaking genius on a lot of levels,” Kaukonen said. "He went and studied with Reverend Davis, and the chord shapes Bob used were Reverend Davis’s chord shapes, and these were not typical kinds of things most fingerstyle guitar players use. It was interesting, really interesting, ‘cause he was playing with a pick, not his fingers. It was really cool, actually.”

Years after Garcia’s death, in 1995, Weir quickly escalated his involvement with Ratdog, his blues-rock-experimental jam band with bassist Rob Wasserman, keyboardist Jeff Chimenti, saxophonist Dave Ellis, drummer Jay Lane, and Matthew Kelly on harmonica and guitar.

He also went on to form the group Further with Lesh as well as Dead & Company alongside former Grateful Dead members that included drummers Mickey Hart and Bill Kreutzmann, guitarist John Mayer, bassist Oteil Burbridge and keyboardist Chimenti.

“Not everybody gets a chance in midlife to reinvent himself,” Weir told us in 1998, “and I'd be remiss to overlook that opportunity and challenge.”

Christopher Scapelliti is editor-in-chief of GuitarPlayer.com and the former editor of Guitar Player, the world’s longest-running guitar magazine, founded in 1967. In his extensive career, he has authored in-depth interviews with such guitarists as Pete Townshend, Slash, Billy Corgan, Jack White, Elvis Costello and Todd Rundgren, and audio professionals including Beatles engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Scott. He is the co-author of Guitar Aficionado: The Collections: The Most Famous, Rare, and Valuable Guitars in the World, a founding editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine, and a former editor with Guitar World, Guitar for the Practicing Musician and Maximum Guitar. Apart from guitars, he maintains a collection of more than 30 vintage analog synthesizers.