How Modes Work – and How to Use Them

Learn the construction, function, and application of the modal system.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

If you're like most guitarists, you cringe when you hear the word "mode."

But there’s really nothing to fear. A mode is just a series of musical tones arranged in a stepwise fashion.

Today the term refers to the scales used in Western music from 400–1500 A.D. Commonly associated with Gregorian chants, these “church modes” – the names and origins of which were derived from Greek cities – also appeared in folk music throughout Europe and the Middle East.

Each mode was said to convey a particular emotion or effect, but their exact meanings were lost due to philosopher Manlius Boenthius’ mistranslation of an important text circa 510. Consequently, the names of the modes were reassigned to the seven degrees of the major scale, and most of their history and original function disregarded.

But rather than focus on such arcane elements, we’ll concentrate here on the construction, function, and application of the modal system we use today.

It’s All The Same Scale

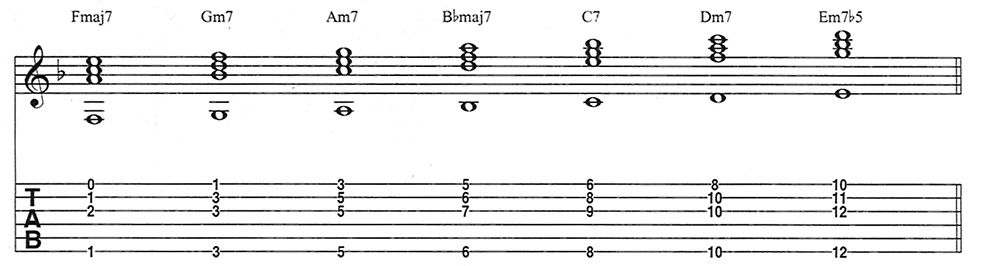

To begin, let’s examine the modal system through the lens of a single scale – the F major scale. By writing it out and stacking 3rds atop each of its notes, we arrive at the F major diatonic system. An analysis of the chords in this system yields the basic harmonic framework (Figure 1) for the Western musical language.

The chords occur as follows:

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

- I major 7th (1, 3, 5, 7)

ii minor 7th (1, b3, 5, b7)

iii minor 7th (1, b3, 5, b7)

IV major 7th (1, 3, 5, 7)

V dominant 7th (1, 3, 5, b7)

vi minor 7th (1, b3, 5, b7)

vii half-diminished 7th, or m7b5 (1, b3, b5, b7)

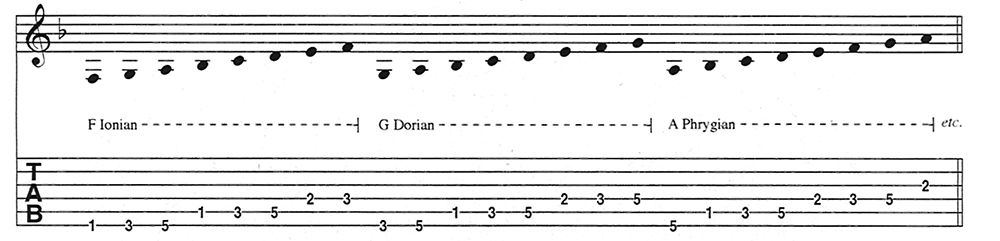

Similarly, playing this seven-note sequence (F, G, A, Bb, C, D, E) starting on each individual scale degree (Figure 2) yields seven different modes within the F major scale.

Here are the names of the major modes in order corresponding to the seven scale degrees:

- Ionian (I)

Dorian (ii)

Phrygian (iii)

Lydian (IV)

Mixolydian (V)

Aeolian (vi)

Locrian (vii)

In the key of F major, then, they are named F Ionian, G Dorian, A Phrygian, Bb Lydian, C Mixolydian, D Aeolian, and E Locrian.

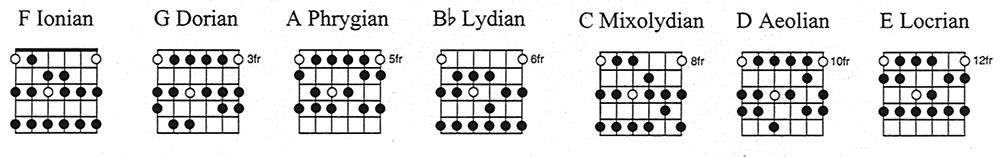

By elaborating on this principle, we arrive at the seven modal patterns. Notice the fret numbers for each one – by placing them in this sequence, we get a series of seven in the same key (Figure 3). Play through this series for a few minutes to get each pattern under your fingers.

The Alterations

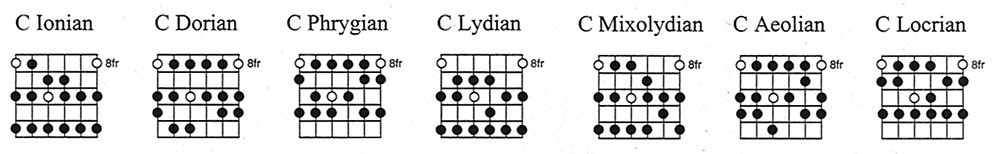

Now let’s free each pattern from any predetermined fret or key, which will allow us to examine each primary position independently. By relating each mode to its root note, we arrive at the follow formulas:

- Ionian: no alterations (same as the major scale)

- Dorian: b3, b7 (any minor scale has a b3)

- Phrygian: b2, b3, b6, b7

- Lydian: #4

- Mixolydian: b7

- Aeolian: b3, b6, b7 (same as the natural-minor scale)

- Locrian: b2, b3, b5, b6, b7

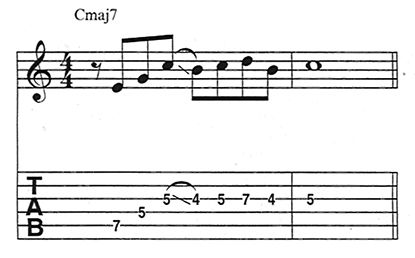

Figure 4 demonstrates this approach by using the 6th string’s 8th-fret C as the root of each mode. For each pattern, first play the mode’s corresponding chord (i.e. Cmaj7 for C Ionian, Cm7 for C Dorian, etc.), and then play the single notes.

How To Apply The Modes

Every mode is built to work with a specific harmony. Below is a list of the most common uses for each mode:

- Ionian: Major triads, major 6th, and major 7th chords

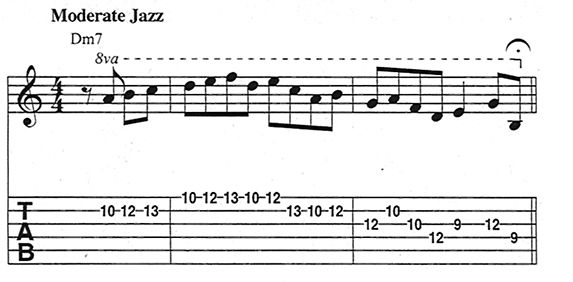

- Dorian: Minor 7th chords (iim7 of ii–V in jazz styles), minor 6th chords (1-b3-5-6)

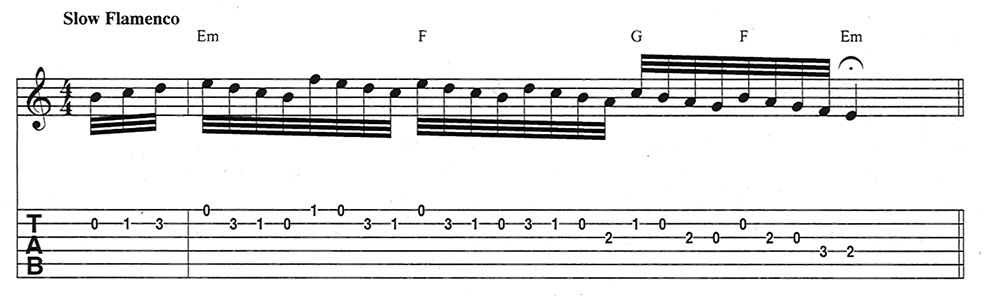

- Phrygian: Spanish progressions (Em–F–G), metal riffs with a b2nd (E5–F5)

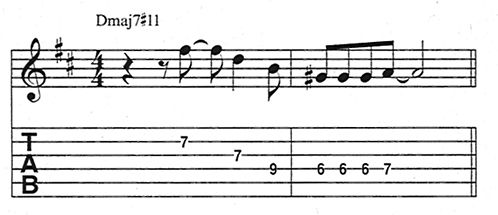

- Lydian: Major 7#11 chords

- Mixolydian: Dominant 7th chords (V7 of ii–V in jazz styles)

- Aeolian: Minor triads, minor 6th, and minor 7th chords

- Locrian: Minor 7b5 chords, viim7b5 chords, (iim7b5 chords in jazz), vii˚ triads

The best way to create a working knowledge of the modes is to play through each one in relation to its harmonic options. Try recording a chord or a bass line that reflects the harmony of the mode you’re practicing, and then play the mode over it. You’ll discover that each mode has a unique emotional or tonal quality.

A deeper exploration will reveal that each mode has what is known as a character pitch – the singular scale degree within each mode that denotes its function in relation to the chord:

- Ionian: 7th

- Dorian: 6th

- Phrygian: b2nd

- Lydian: #4th

- Mixolydian: b7th

- Aeolian: b6th

- Locrian: b5th

The difference between the #4th in Lydian and the b5th in Locrian is the trajectory. Here’s a simple rule: Flats descend, sharps rise. In the example here, we use a sharp (#) or a flat (b) to indicate the raising and lowering of scale degrees to avoid the confusion of flats and sharps in regard to key signatures.

Figure 5 shows the tendency of the Ionian mode’s 7th to act as a leading tone resolving to the tonic.

Figure 6 illustrates a Dorian idea similar to those that trumpeter Miles Davis played on his classic “So What” recording. Notice the strong presence of the 6th scale degree, which has an unusual balance of tension and stability.

Figure 7 is an example of an old Phrygian flamenco idea. The lowered 2nd of the mode – sort of a leading tone in reverse – creates a tension that must be resolved down to the tonic.

A famous Lydian motif is found in Figure 8. Notice how the raised 4th has the effect of making the 5th a temporary tonic.

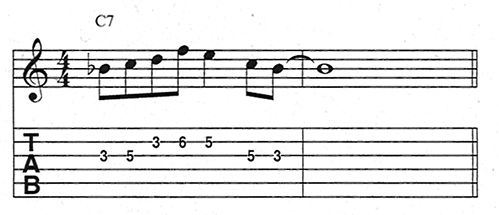

Mixolydian’s b7th creates the sound of a dominant 7th chord. This mode often colors the blues, where there is a tendency to stay on the b7th rather than indulge the dominant’s tendency to resolve up a 4th or down a 5th (Figure 9).

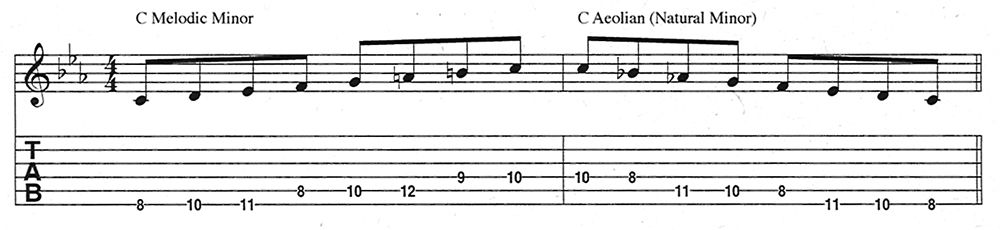

The Aeolian mode appears frequently in Baroque and late Romantic music as a descending scale (Figure 10).

The melodic-minor scale (1, 2, b3, 4, 5, 6, 7), meanwhile, is often used on ascending phrases to effect a lean in the direction of the line. Without the melodic-minor concept, the b6th of the Aeolian mode leads us into the 5th scale degree, just as a bVI chord leads in the V7 of a minor-blues turnaround (Figure 11).

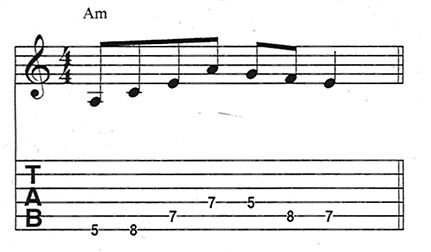

The Locrian mode is also called the half-diminished scale, as it fits perfectly over that chord. Figure 12 contains a dark Locrian blues lick.

On your own, practice all seven patterns in each mode. Work on one mode at a time until you can sing it.

Lastly, since music is a paradoxical language, try this: when playing scales, think vertically, and when playing chord, think horizontally.

Guitar Player is the world’s most comprehensive, trusted and insightful guitar publication for passionate guitarists and active musicians of all ages. Guitar Player magazine is published 13 times a year in print and digital formats. The magazine was established in 1967 and is the world's oldest guitar magazine. When "Guitar Player Staff" is credited as the author, it's usually because more than one author on the team has created the story.