Extended & Altered Chords: Expand Your Vocabulary with Advanced Chord Voicings

Explore the construction and applications of extended and altered chords, and learn more about advanced voicings.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Ever crack open an intermediate-to-advanced chord book only to be overwhelmed by the multitude of ambitious voicings?

Sure, those chords have cool names, but what do they mean? Some sound great, others not so much. And how the heck do you use them? What styles of music do they fit in, and how do they work with progressions?

But don’t fear! In this lesson, we’ll explore the construction and applications of extended and altered chords and clear up some of the confusion that surrounds these advanced voicings.

EXTENDED CHORDS

An extended chord is simply a 7th chord (maj7, m7, dom7, etc.) with an added:

• 9th (an octave plus a 2nd)

• 11th (an octave plus a perfect 4th)

• 13th (an octave plus a major 6th)

or any combination thereof. Extended chords are generally used when a richer harmonic “color” is desired. Since 9th chords are among the most popular extended chords, let’s begin with them.

NINTH CHORDS

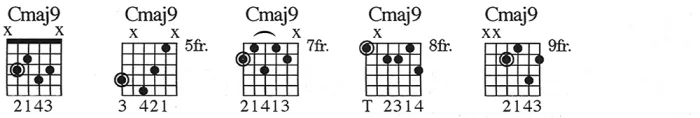

If you were to take a Cmaj7 chord (C-E-G-B) and add a D note to the voicing, you would be creating a Cmaj9 (R[oot]-3–5-7-9; C-E-G-B-D). Some feel that the inclusion of the 9th adds a bittersweet quality to the simple beauty of a maj7 chord. You be the judge as you play through the Cmaj9 voicings in FIGURE 1.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

FIGURE 1

Notice that some of the voicings omit the 5th degree (G). This is a common and acceptable procedure when dealing with extended chord voicings. Remember, all of these voicing are movable, so practice them in a variety of keys.

FIGURE 2 offers a musical example that teams up two voicings of a Cmaj9 chord with an Fmaj9 chord in an arpeggiated I-IV progression in the key of C. Repeating the first two measures is a great exercise, both for memorizing the fingerings and for frethand coordination.

FIGURE 2

Bear in mind, you don’t have to wait until you see a maj9 chord symbol on a chart to play one. For example, a Cmaj9 chord can be used as a “substitution” for a Cmaj7 chord in most situations. Cmaj9 can sometimes serve as a replacement for the closely related Cadd9 (C-E-G-D) as well.

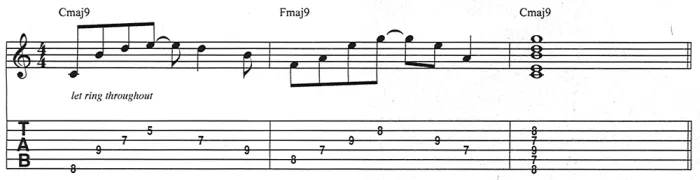

Take a C7 chord (C-E-G-Bb) and add the 9th degree (D) and you have a C9—or C dominant 9th chord (R-3-5-b7-9; C-E-G-Bb-D). When learning new voicings, always try to relate them to those that you already know, and it will eliminate the hard labor of starting from scratch with every new voicing.

With that in mind, if you were to lower the 7th degree of a Cmaj9 chord by a half step, you would create a C9 chord (and vice versa).

For example, take a look at the C9 voicings in FIGURE 3.

FIGURE 3

Upon close inspection, you’ll discover that they are the exact dominant counterparts to the major voicings found in FIGURE 1. You’ll have to change your fret-hand fingering for some, but otherwise the only difference lies in the 7th degrees (B for the Cmaj9, Bb for the C9).

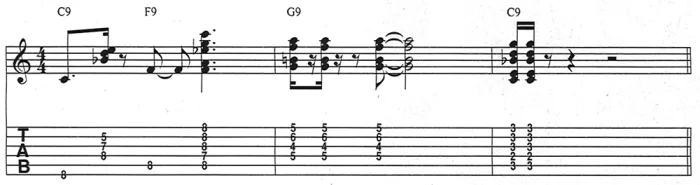

Particularly conspicuous in blues, jazz and funk, dominant 9th voicings are a popular, colorful substitute for the often overworked dominant 7th chord. FIGURE 4 sets C9, F9 and G9 voicings in motion over a funk I7-IV7-V7 progression. As in FIGURE 2, this is a good one to loop as a two-measure jam for learning purposes.

FIGURE 4

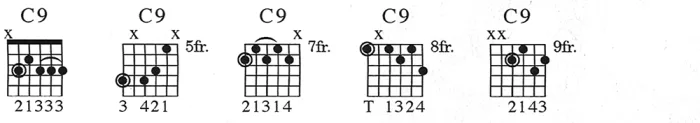

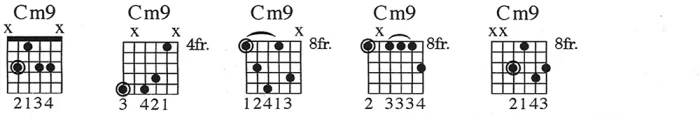

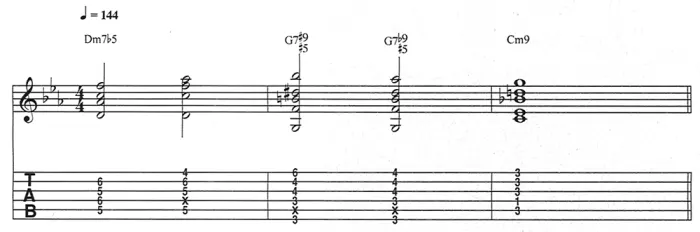

A common misconception is that minor 9th chords contain a minor 9th (b9th) extension. Not so! Like maj9 and dome9 chords, m9 chords contain a natural, or major 9th degree. For example, a Cm9 chord is spelled C-Eb-G-Bb-D (R-b3-5-b7-9) as in FIGURE 5.

FIGURE 5

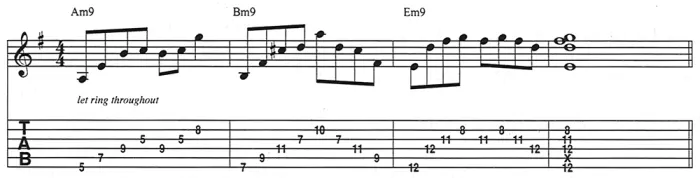

Equally at home in rock, blues, jazz, funk and pop, dark and moody minor 9th chords are commonly used in place of minor 7th (R-b3-5-b7) and minor add9 (R-b3-5-9) chords. Listen to the atmosphere they generate are you play through the example in FIGURE 6.

FIGURE 6

ELEVENTH CHORDS

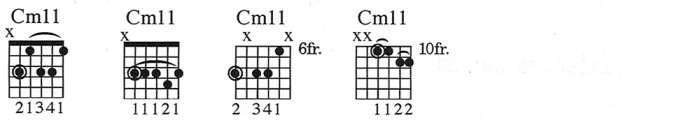

Eleventh chords are 7th or 9th chords with an added 11th degree. The most common 11th chords are minor 11ths (e.g., Cm11: C-Eb-G-Bb-D-F).

FIGURE 7 shows four Cm11 voicings.

FIGURE 7

You’ll notice that only the first voicing includes the 9th (D). This brings up an important point regarding extensions. A chord gets its name from its highest extension, whether or not the lower ones are included in the voicing. Useful for voice leading and chord melody purposes, minor 11th chords are often used for the ii chord in major keys (Am11 in the key of G. FIGURE 8), and the iv chord in minor keys (Fm11 in the key of C minor).

FIGURE 8

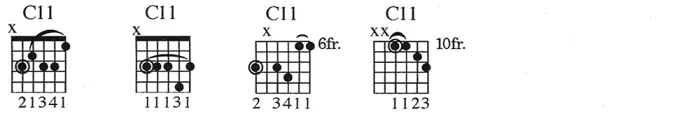

FIGURE 9 shows four voicings of a C11 (C dominant 11th) chord. Dominant 11th chords are particularly useful in V chord applications in major keys (C11 in the key of F; Bb11 in the key of Eb, etc.).

FIGURE 9

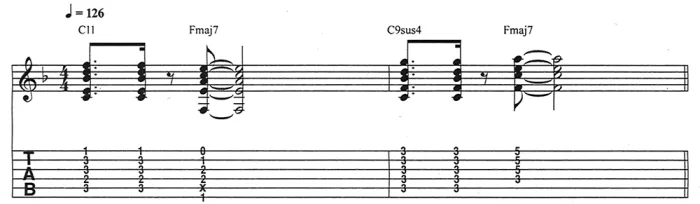

Many guitarists dislike the minor 9th (inverted minor 2nd) “rub” of the 3rd against the 11th in dominant 11th chords and substitute dom9sus4 (R-4-5-b7-9) voicings in their place (FIGURE 10.)

FIGURE 10

It is because of this same dissonance that major 11th chords are rarely if ever encountered, so we’ll pass on them for the moment. When such a sound is desired, the chords maj7add4 or maj9add4 are generally used.

THIRTEENTH CHORDS

The 13th is the highest possible chord extension. While 13th chords can contain a 9th or an 11th, those extensions aren’t necessary and are often dropped from guitar voicings.

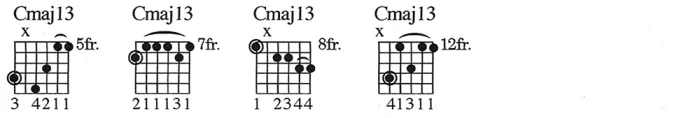

For example, to convert a Cmaj7 into a Cmaj13 chord, you only need to add the 13th (A). Although each of the Cmaj13 chords found in FIGURE 11 includes a 9th (D) in the voicing, that 9th could be omitted without having to rename the chord. Again, due to the dissonance factor, the 11th is routinely omitted from maj13th chords.

FIGURE 11

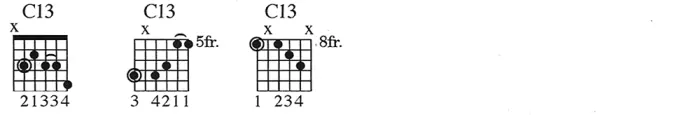

Add an A note to a C7 or C9 chord and you have a C13 voicing (FIGURE 12).

FIGURE 12

As with major 13th chords, the presence of a 9th isn’t required in a dominant 13th voicing, and the 11th is routinely omitted.

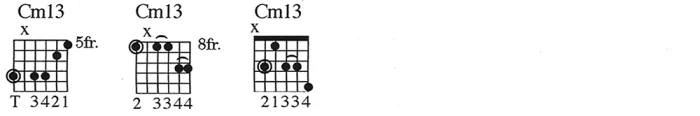

Minor 13th chords (R-b3-5-b7-9-11-13) are the exception to the “omitted 11th rule.” For instance, in a Cm13 chord, the 11th (F) is a relatively consonant major 9th (inverted major 2nd) away from the b3rd (Eb), making it an acceptable extension for minor 13th voicings (witness the first Cm13 voicing in FIGURE 13).

FIGURE 13

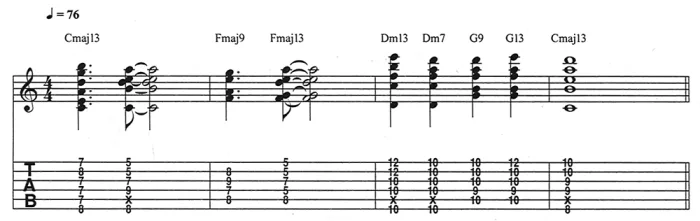

For an example of the luscious sound of 13th chords in action, check out the I-IV-ii-V-I, C major progression in FIGURE 14.

FIGURE 14

ALTERED CHORDS

Generally speaking, an altered chord is a chord with either a b5th, b9th, #9th or any combination thereof. As with extended chords, altered chords can be grouped into three categories: major, minor and dominant. Since the latter category is by far the most common of the three, we’ll begin there.

ALTERED DOMINANT CHORDS

The voicing possibilities in the altered dominant chord department are so vast that they can quickly boggle the mind. One way to guard against brain overload is to place them into subcategories: those containing a single alteration, and those with two or more alterations.

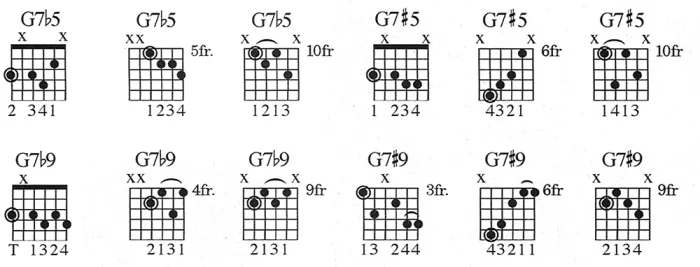

The voicings in FIGURE 15 represent the former category: dominant 7th chords with a single alteration.

FIGURE 15

The first three lower the 5th (D) of a G7 chord a half step, to Db, to create a G7b5, an intrinsic chord in big band swing and jazz music. The next three raise the 5th a half step, to D#, resulting in a G7#5 (or G augmented 7th, written Gaug7 or G+7). This is a popular altered V chord choice in the major and minor progressions of jazz and blues music.

Our next trio of voicings lower the 9th (A) of a G9 chord a half step, to Ab, to create a G7b9 chord, one of the most popular altered V chords in jazz. The final three raise the 9th a half step to form the mighty dom7#9 chord—the mother of all altered chords in the rock world. In addition to being the most commonly used altered V chord, it often functions as the i chord in minor keys (FIGURE 16).

FIGURE 16

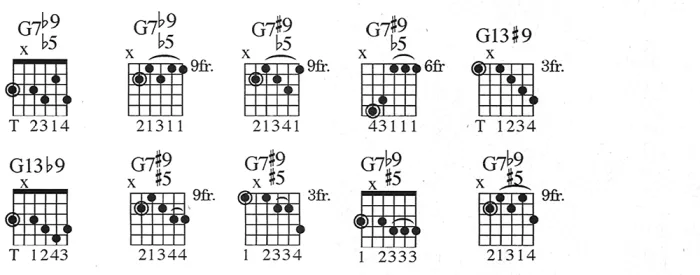

For you high-strung guitarists who thrive on tension, there is the second category of altered dominant chords—those with two or more alterations. Again, using a basic G7 for the foundation, FIGURE 17 offers a variety of super-altered dominant chords. These are the chords which, when played alone, can sound downright ornery, but when put in the right place at the tight time, can generate smooth resolutions.

FIGURE 17

For example, the G7b5(b9) works particularly well resolving to a dominant chord such as C9; the G7b5(#9) sounds great as a set-up chord for a Cm13; and both the G13#9 and G13b9 function well in a V chord setting in the key of C major.

Finally, the G7#5(#9) and G7#5(b9) voicings fit neatly into the V chord slot of a C minor progression. (FIGURE 18).

FIGURE 18

OTHER ALTERED CHORDS

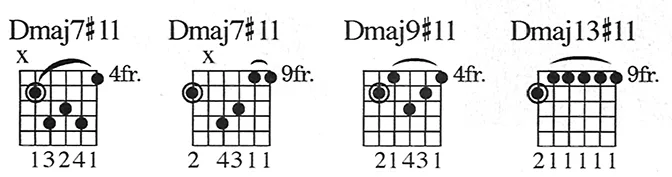

Contrary to popular belief, altered chords are not exclusively dominant in quality, as the major #11 voicings found in FIGURE 19 attest.

FIGURE 19

Native to jazz/fusion and progressive instrumental rock, these chords commonly function as the IV chord in major keys and as the I chord in Lydian (1 2 3 #4 5 6 7) progressions.

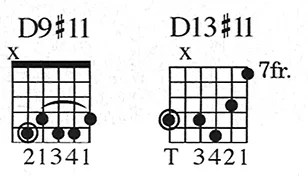

FIGURE 20 offers two examples of dominant #11 voicings.

FIGURE 20

These colorful chords can shine in secondary dominant situations—for example, when the IV chord in a major key is dominant in quality instead of major (D9#11 in the key of A major, FIGURE 21).

FIGURE 21

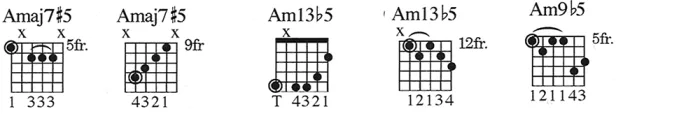

The Amaj7#5 chords (bIII chord of F# harmonic and F# melodic minor) found in FIGURE 22 offer yet another example of altered-major-type chords, while the Am13b5 and the Am9b5 voicings represent the less widespread altered minor chord variety.

FIGURE 22

INVERSIONS

All of the chords we’ve discussed so far have been root-position chords (where the lowest note is the root of the chord). But when any other chord tone is placed at the bottom of a voicing, it becomes an inverted chord, or inversion. Although there are other possibilities, the most common inversions are “3rd in the bass” (first inversion) and “5th in the bass” (second inversion).

Not only is the use of inversions a good way to stay out of the bass player’s frequency space—it’s also a handy method for including more extensions and alterations in your chords and for gaining easier access to some of those merciless, joint-stretching voicings.

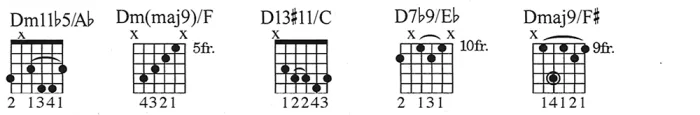

The inverted chords in FIGURE 23 offer several examples of “easy-reach” extended and altered voicings. Note that the root has been deleted in all of these chords except for the last.

FIGURE 23

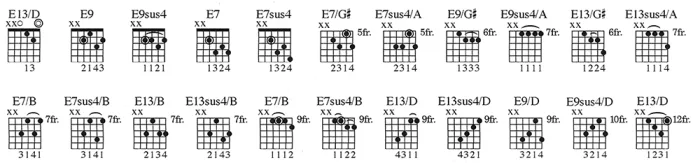

FIGURE 24 is an inversion exercise guaranteed to turn you into an E dominant funk monster. These are all E dominant chord types located exclusively on the top four strings—perfect for an E9 chord vamp, a staple of the funk genre.

FIGURE 24

OPEN-STRING VOICINGS

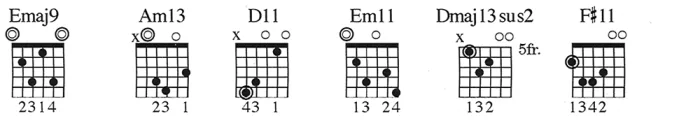

Like inversions, open-string voicings (chords involving one or more open strings) can come in handy for creating extended voicings. In addition, they furnish a rich, ringing timbre ideal for small-group and solo settings. Check out FIGURE 25 for some big, “phat” examples.

FIGURE 25

Think of these as “gateway” chords and use them as guides for creating some open-string voicings of your own.

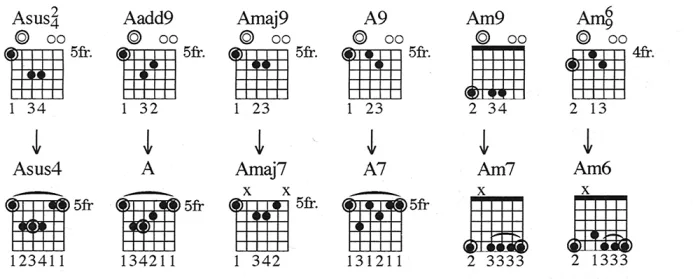

FIGURE 26 represents another approach to creating open-string voicings.

FIGURE 26

This one involves taking a common barre-chord shape and “opening up” the voicing to allow selected strings to ring open. The chords in the top row are the open-string voicings, of course, while the ones in the bottom row represent the basic barre-chord voicings they are derived from. Apply this method to other barre-chord shapes to see what you can come up with.

Happy hunting.

Guitar Player is the world’s most comprehensive, trusted and insightful guitar publication for passionate guitarists and active musicians of all ages. Guitar Player magazine is published 13 times a year in print and digital formats. The magazine was established in 1967 and is the world's oldest guitar magazine. When "Guitar Player Staff" is credited as the author, it's usually because more than one author on the team has created the story.