Prince told her she was “too funky” and Bruno Mars sent her one of his signature Strats: Ella Feingold weaves magic with her funky playing, and this lesson in her style will sharpen up your rhythm work in no time

Feingold has played with Bruno Mars, Queen Latifah, Erykah Badu, Alicia Keys, and Jay-Z, and was taught directly by the legendary Chalmers “Spanky” Alford. This guided tour of her approach is a funk guitar one-stop shop

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Prince slyly told her she was “too funky.” Bruno Mars sent her one of his signature Fender Strats, and Bootsy Collins and Ray Parker Jr. left glowing comments on her Instagram posts.

Guitarists are usually lauded for their soloing prowess, but Ella Feingold doesn’t solo – she doesn’t feel the need. Instead, she weaves magic with her rhythm playing, creating a unique and soulful blend of classic and forward-looking funk guitar that’s fueled by her uncanny sense of time.

In 2022, Feingold received a Grammy participation certificate for her playing on the Record of the Year winner, Leave the Door Open, by Silk Sonic, the R&B duo featuring Mars and singer/rapper Anderson .Paak.

At the time that Mars invited her to perform on their album, An Evening With Silk Sonic (which won four Grammys that year), Feingold had already made a name for herself playing with artists such as Queen Latifah and Erykah Badu. But participating in the project was key to her making it through a challenging period of her life, during which she hadn’t touched her guitar in five years. As we’ll see, there’s more to the story. But first, let’s check out some of Ella’s playing.

For this lesson, we’ll be selecting from Feingold’s funky trove of Instagram reels.

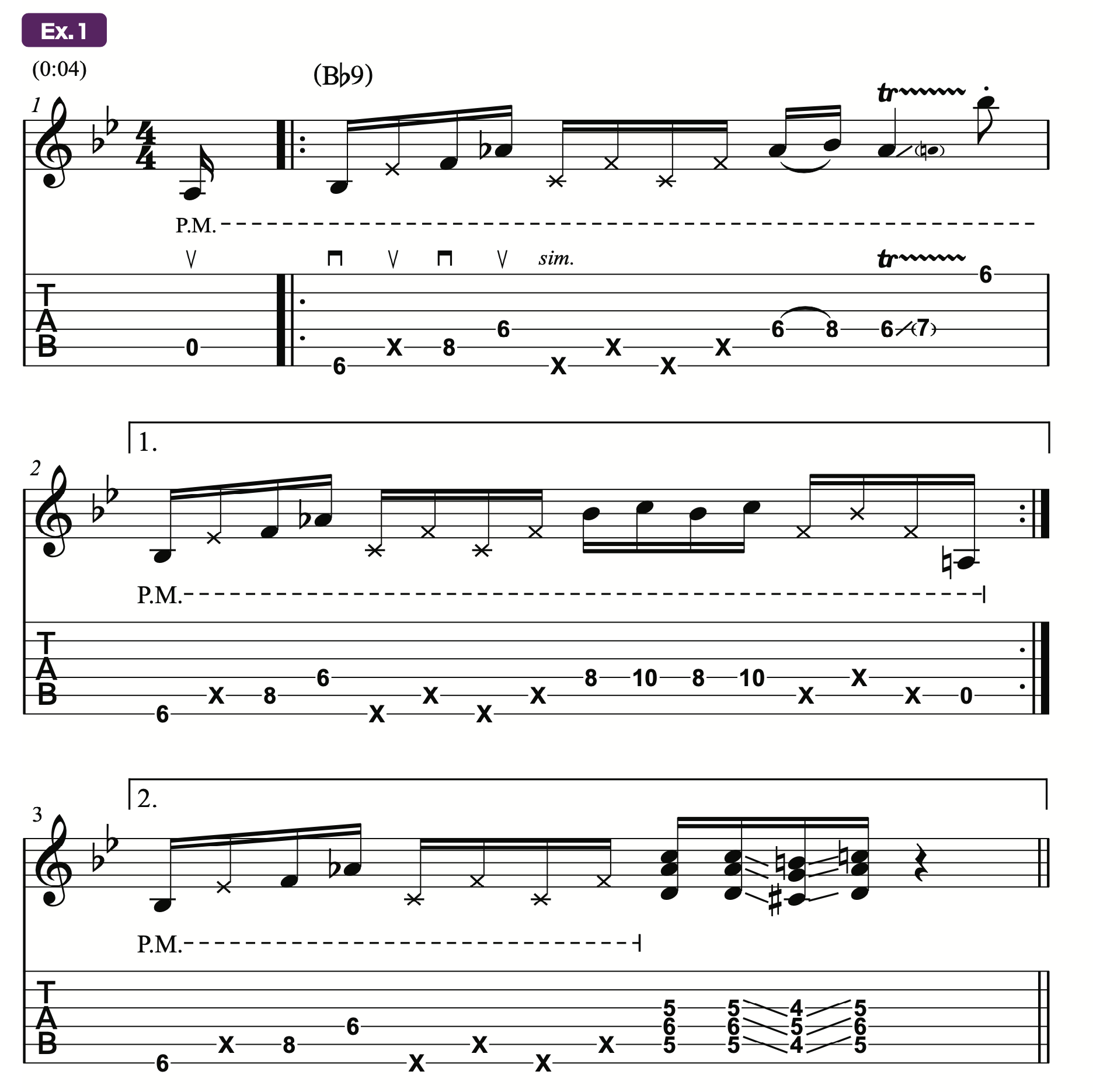

Ex. 1 is one of her chill single-note grooves. Note how she creates many interesting musical twists and turns while using just one chord, Bb9.

The Godfather of Soul, James Brown, was a master of conceiving one-chord grooves and was a major influence on Feingold’s playing. Her use of deadened notes (indicated with Xs) is elemental to funk playing, as they percussively propel the music along, much as a drummer would.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

As it happens, this line of thinking is essential to Feingold’s overall approach.

“I don’t look at my instrument as a guitar; I look at it as pitched percussion or a drum,” she explains. To deaden notes, simply lift your finger so that it lightly rests on the string, creating a percussive sound when picked. Also contributing to this effect is the guitarist’s use of palm-muting (P.M.), which is performed by lightly resting the pick hand on the bridge, lending an additional muffle to the note attack.

The sliding trill in bar 1 is really meant to function more as a vibrato; quickly shimmy your fret-hand index finger back and forth between the 6th and 7th frets. You can substitute a traditional vibrato if you’d like, but the “trill vibrato” adds a unique spice here. To seamlessly play the high Bb note that follows, fret it with the base of your index finger, as if creating a barre. Note that Feingold demonstrates the example slowly at 0:35 in the video.

Now 43, Feingold began her career as a working guitarist while a high school sophomore in Swampscott, Massachusetts in the late ’90s.

“It’d be a Monday night, and I’m supposed to be doing homework, but I’m out playing a club gig,” she recalls. In 2002, after finishing high school, she started her first year at Berklee College of Music, before dropping out during finals week to take advantage of a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to study privately with Chalmers “Spanky” Alford, the enormously influential jazz, gospel, and neo-soul guitarist, whom she calls “my favorite musician in the world.”

Feingold discovered he was teaching at a music store in Alabama, and they would play guitar for each other over the phone. After a few conversations, Alford invited her to his home to spend the week hanging out and playing guitar together.

“He had a very unique way of playing the instrument,” she recalls. “So I just practiced the things that he showed me, and when I got home to Boston, I was a completely different musician.”

Feingold’s love for Alford’s style is a major contributor to her sound. During our conversation, she demonstrated one of his unique contributions, which was to incorporate Joe Pass–style jazz voicings with gospel and neo-soul guitar playing.

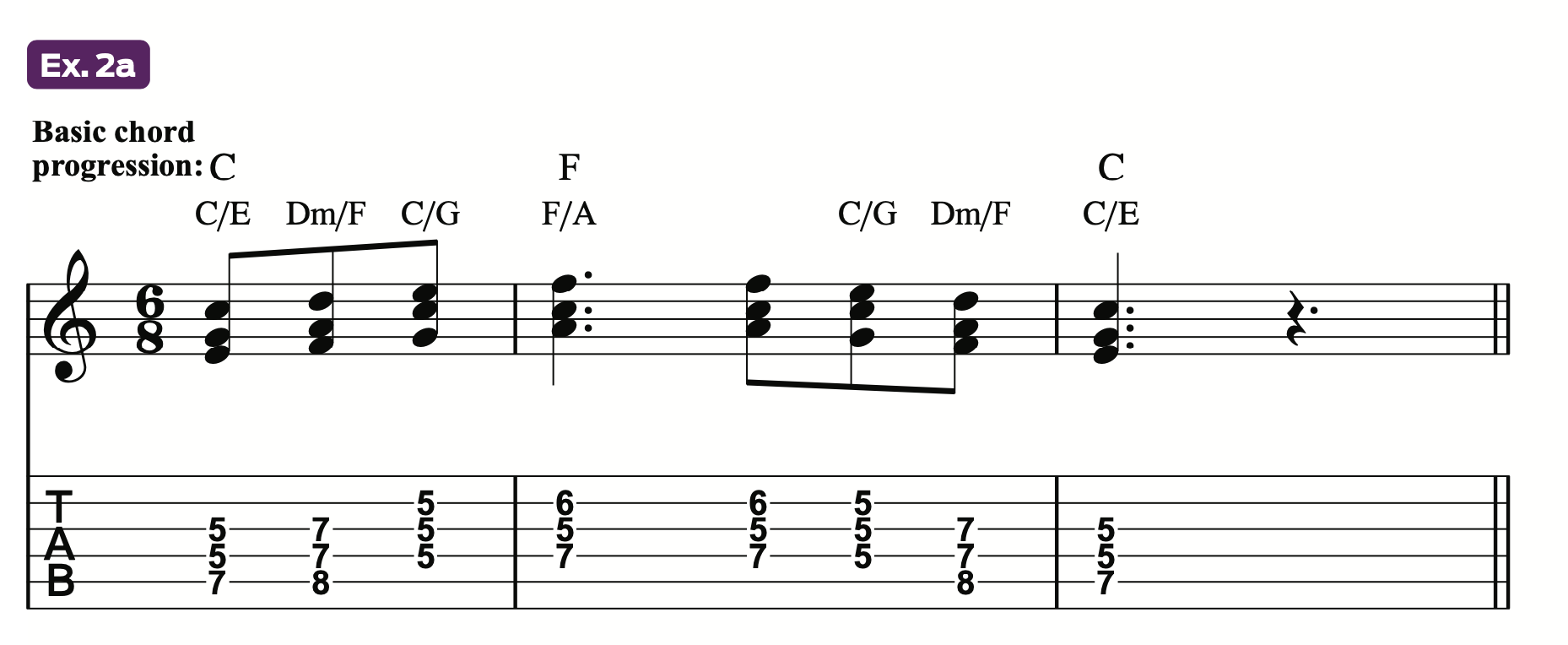

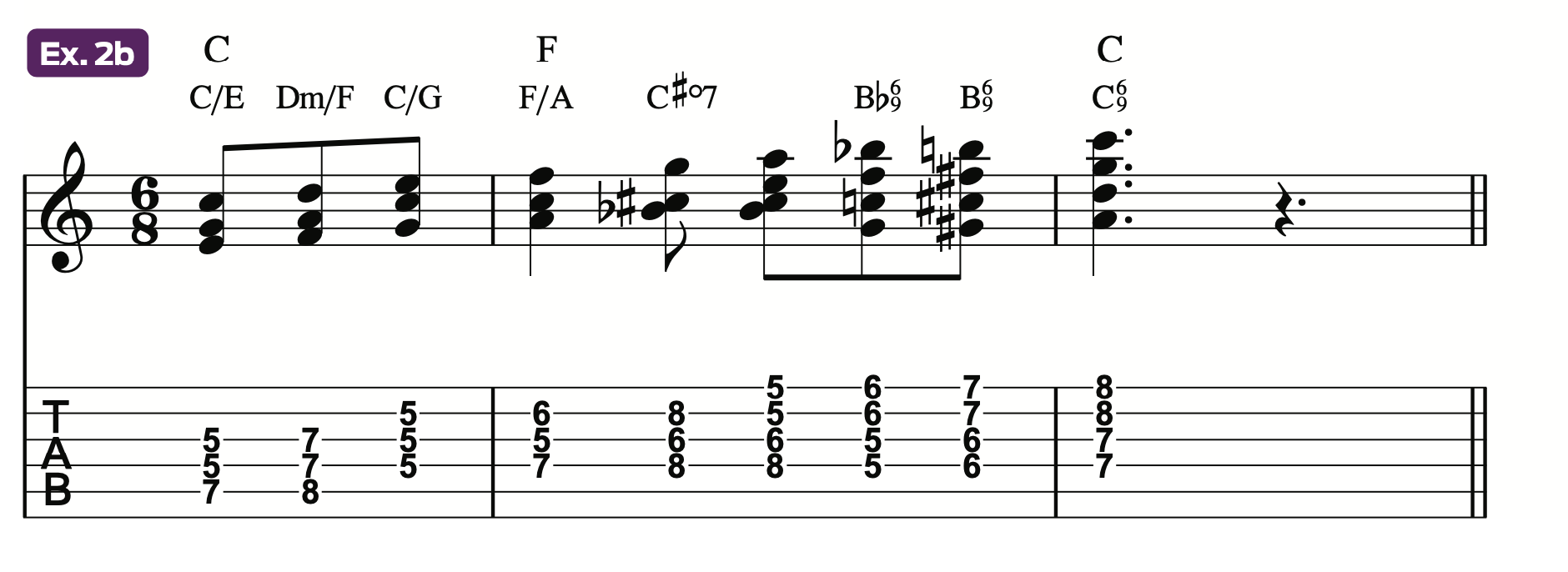

Ex. 2a demonstrates a standard gospel-style approach using a simple progression in the key of C major, moving from the I (one) chord, C, to the IV (four), F, and back.

Ex. 2b, however, presents a more colorful path that “Spanky” might have taken, employing jazz voice leading by adding diminished 7 and major 6/9 chords. Feingold’s deep chordal knowledge and ability to draw from a plethora of different voicings is one hallmark of her playing.

Feingold believes Alford is part of the reason she shares so much about herself and her music online. “He taught me so much about musical generosity and generosity as a person,” she says.

Just about every day on her Instagram, Feingold presents bite-sized musical concepts that guitarists can quickly incorporate into their own playing, all while demonstrating a wide variety of approaches to rhythm guitar.

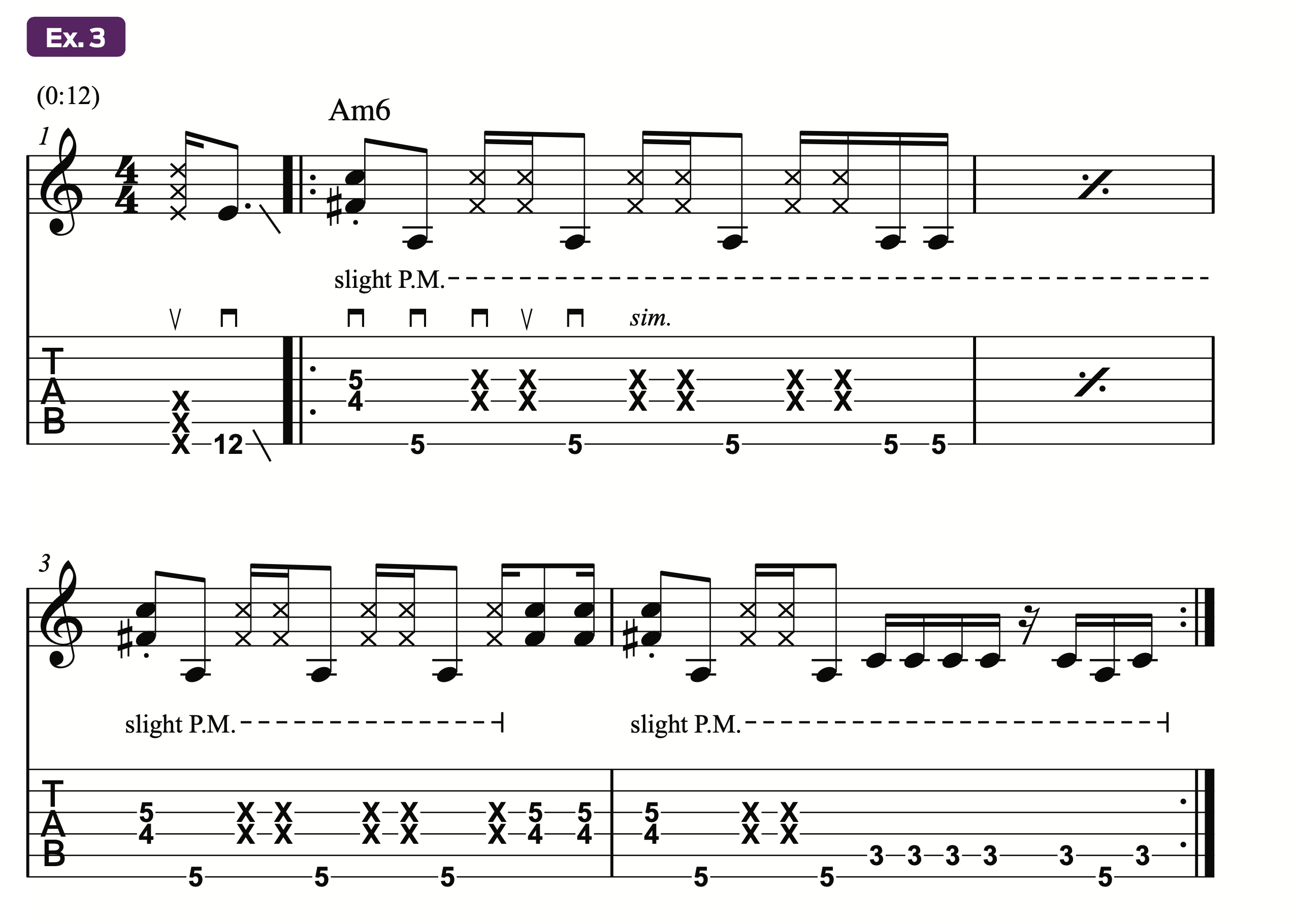

Ex. 3 is a James Brown–esque groove featuring some “chicken scratch,” the rhythmic strumming of deadened strings associated with another of Feingold’s idols, guitarist Jimmy “Chank” Nolen, who was a mainstay of James Brown’s band in the ’60s and ’70s.

The dyad (two-note chord) on the downbeat of bar 1 illustrates the old adage “Little things mean a lot.” The small black dot under the note heads here indicates staccato articulation – technically 50 percent of the note’s normal duration. Feingold employs a light palm mute with her pick hand, which shortens the chord’s duration, but here it’s not quite enough.

After sounding the notes, quickly loosen your fret hand’s grip on the strings so that they break contact with the frets, but without letting go of the strings. If you were to play the example tenuto – that is, with normal, non-staccato note durations – it would lack the desired funkiness and wouldn’t groove with the same oomph.

In 2005, musical director Rickey Minor (The Tonight Show, American Idol) tapped Feingold to play guitar in Queen Latifah’s band for that year’s Sugar Water Festival tour, which featured a host of major artists, including Erykah Badu and Jill Scott. The guitarist made valuable connections that summer and later worked extensively with Badu. It also led to her auditioning for Prince at his home over two nights, when he gave her the aforementioned kudos.

But later, in 2014, Feingold had what she calls “a falling out with the guitar.” Feeling unhappy and lost while living in Los Angeles, she left her main gig in Badu’s band after eight years for a quieter life in western Massachusetts’ Berkshire mountains. For the next five years, she set guitar aside while making a living as a professional orchestrator and arranger for film and video games, including Destiny (a soundtrack of her orchestrations for the game will be released this summer).

As Feingold explains, her emotional turmoil stemmed from the fact that she had always known she was a trans woman, but “I didn’t live like that because I didn’t think the world would accept me.”

Toward the end of her five-year disconnect from guitar, she met Bruno Mars through a mutual friend, and he subsequently asked her to play on the Silk Sonic record. Despite not having played guitar for years, she couldn’t say no to such an opportunity. Throughout the making of the album, she transitioned, and both events contributed to the blossoming of her personal life as well as her relationship with her guitar.

“I studied a lot of different styles and guitar players, but I never really felt like I had a sound until I transitioned,” she says.”I feel like I just emerged through my instrument by simply being authentic.”

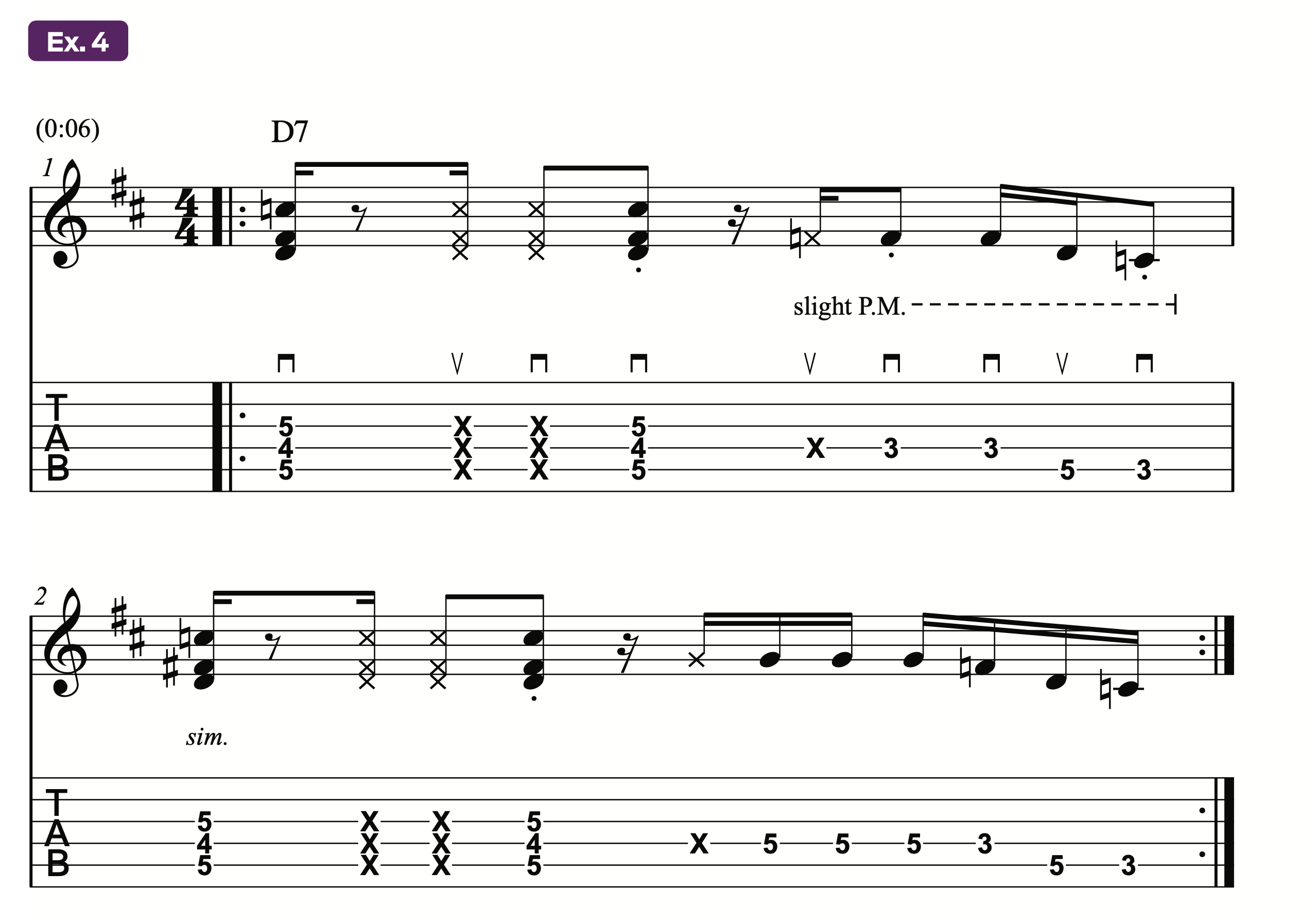

Ex. 4 is another window into Feingold’s expressive style, in which she enjoys seamlessly combining multiple guitar parts into one playable groove. Incorporating a bit more chicken scratching, she creates a chordal rhythmic figure offset by a single-note riff. Note in bar 1 how she uses both deadened and staccato notes on beat 3, demonstrating just how essential these nuances are if you want to play funk guitar authentically.

Her time with Alford convinced Feingold that she wanted to fully understand the essence of how he played. At his recommendation, upon returning to Boston, she joined a Black Pentecostal church, where she immersed herself in gospel music for a full year.

There were no rehearsals or discussions about the songs with regard to key or form, and no one told her what the chord changes were. Unacquainted with gospel’s rapid-fire chord changes, she had to quickly learn how to “get in where I fit in,” she says. The experience strengthened her intuition.

“I’m not going to hit every chord that they’re playing,” she explains, “so how do I get inside of this music and contribute something? Some of it was guide tones, sound effects, octaves. It taught me a lot about how to just listen and respond.”

At the same time, she was playing instrumental jazz/funk music at Boston clubs like Wally’s Jazz Café. Once again, there were no rehearsals, and since there was usually no keyboard player present, she would play rhythm all night.

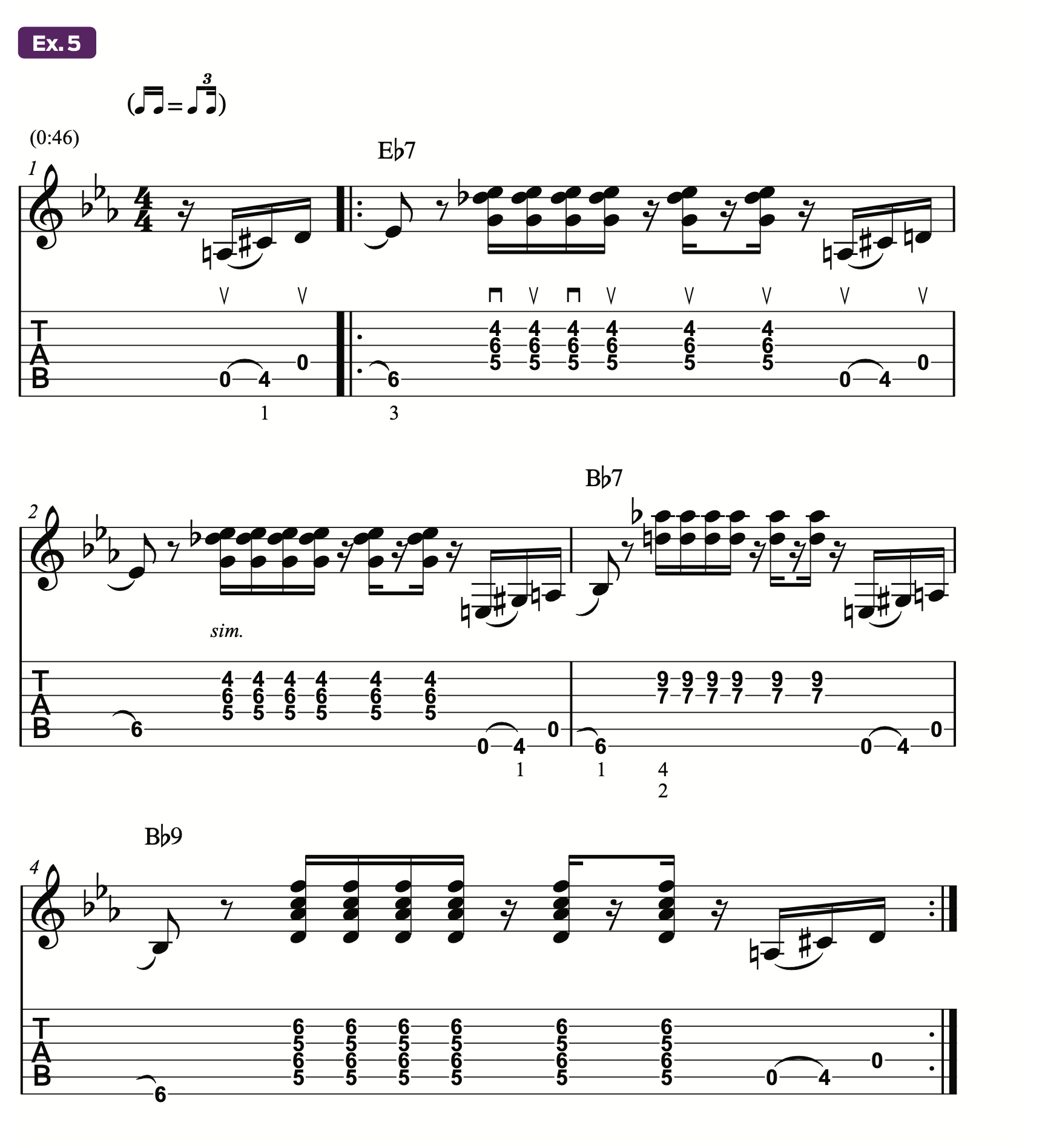

Feingold incorporates all sorts of ingenious techniques borrowed from different instruments, like the one she picked up from hearing the legendary bassist James Jamerson on classic Motown records, as shown in Ex. 5.

As she explains in the corresponding video, the example uses open strings as passing tones, which are especially useful in flat keys, where they’re often non-diatonic (out of key). Playing in the key of Eb major here and with a swing-16ths feel, Feingold starts with a non-diatonic open A note hammered-on to the C# on the 4th fret.

She then strikes a (diatonic) open D string, followed by a “hammer-on from nowhere” to the Eb on the 5th string. If you replace the open D with the same pitch on the 5th string (5th fret), it would just be a rather conventional-sounding passage, but playing it like this lends the phrase a quirky charm. In this way, Feingold expresses her personality through her rhythm playing in much the same way lead guitar players do when soloing.

Another key element of Feingold’s style is her uncanny ability to create different feels by playing either slightly “ahead of” or “behind” the beat (the latter is often referred to as playing “in the pocket”).

When asked how to begin working on this, Feingold pointed to one of her posts explaining how the late Detroit record producer J Dilla would create a behind-the-beat feel with his drum programming.

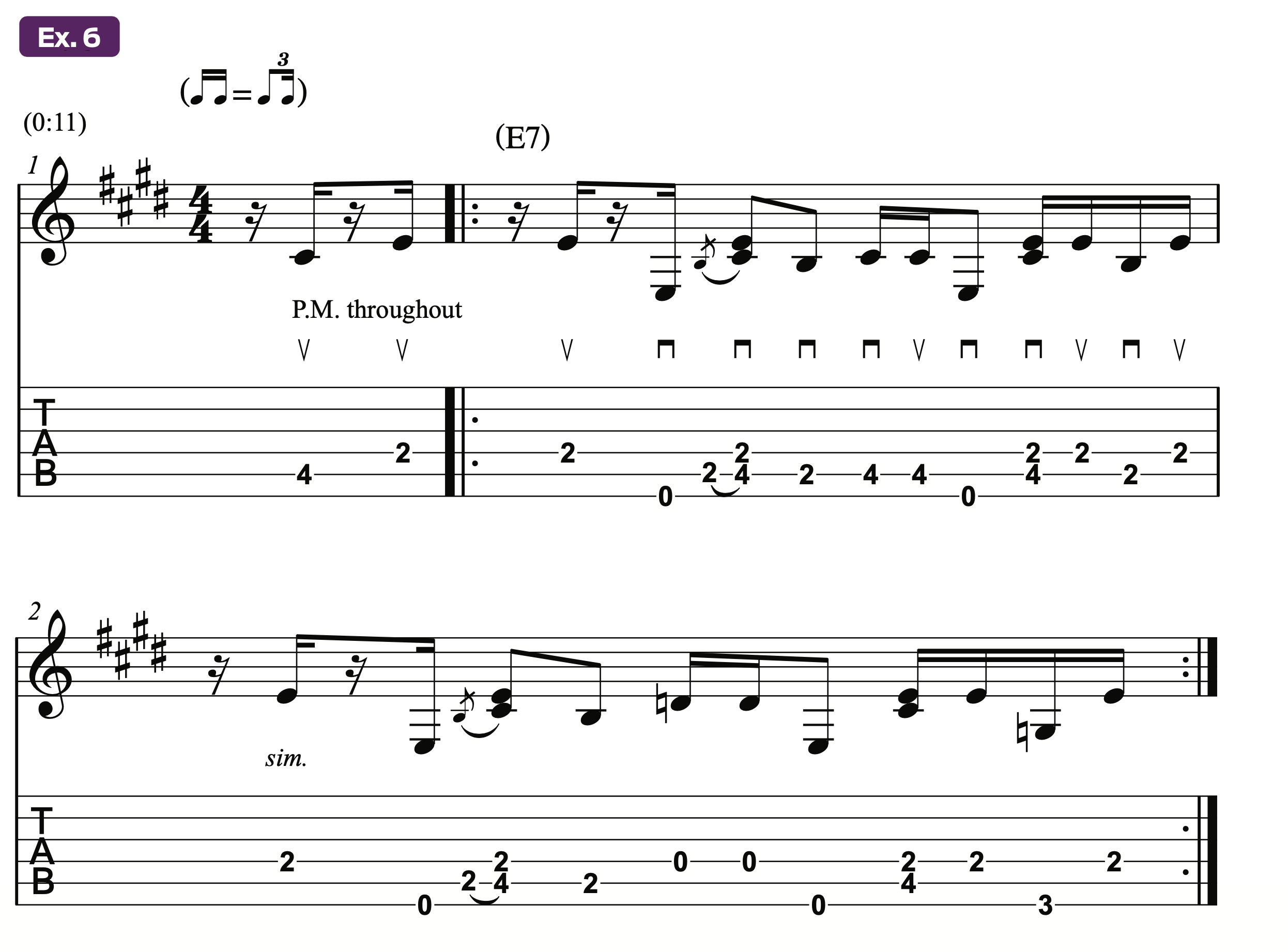

Ex. 6 is a nifty single-note riff Feingold uses to concretely convey how to lock into playing a classic J Dilla–style groove, here over D’Angelo’s Feel Like Makin’ Love. Using the accompanying video, play along with her, feeling the time as she does. As the guitarist explains in the on-screen text, she plays the strong beats (1 and 3, where the kick drum hits) directly on the beat and everything in between a bit behind, which you can also think of as “late” or “lazy.”

As Feingold’s personal life flourished, her playing career was also rekindled. Using her arsenal of vintage gear, the guitarist has since performed with a host of major artists, including Alicia Keys, Jay-Z, Common, and the Roots. She is currently working on separate records with Charlie Hunter and Bootsy Collins, while also being known online as a respected teacher, with more than 30,000 followers.

Like another of her heroes, Fred Rogers, creator of the classic children’s TV series Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood, Feingold strives to create an environment (via her Instagram and Patreon) where everyone can come and feel comfortable learning – in her case, how to funk things up.

Jeff Jacobson is a guitarist, songwriter and veteran music transcriber, with hundreds of published credits. For information on virtual guitar and songwriting lessons or custom transcriptions, reach out to Jeff on Twitter @jeffjacobsonmusic or visit jeffjacobson.net.