"I'm gonna live this for the next year, and then maybe I’ll go torch some guitars." Jerry Cantrell on the future of Alice in Chains and his heavy new solo album

Cantrell, who teamed up with Duff McKagan and other pals for his new record, tells Guitar Player, "It’s no secret where my loyalty lies"

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

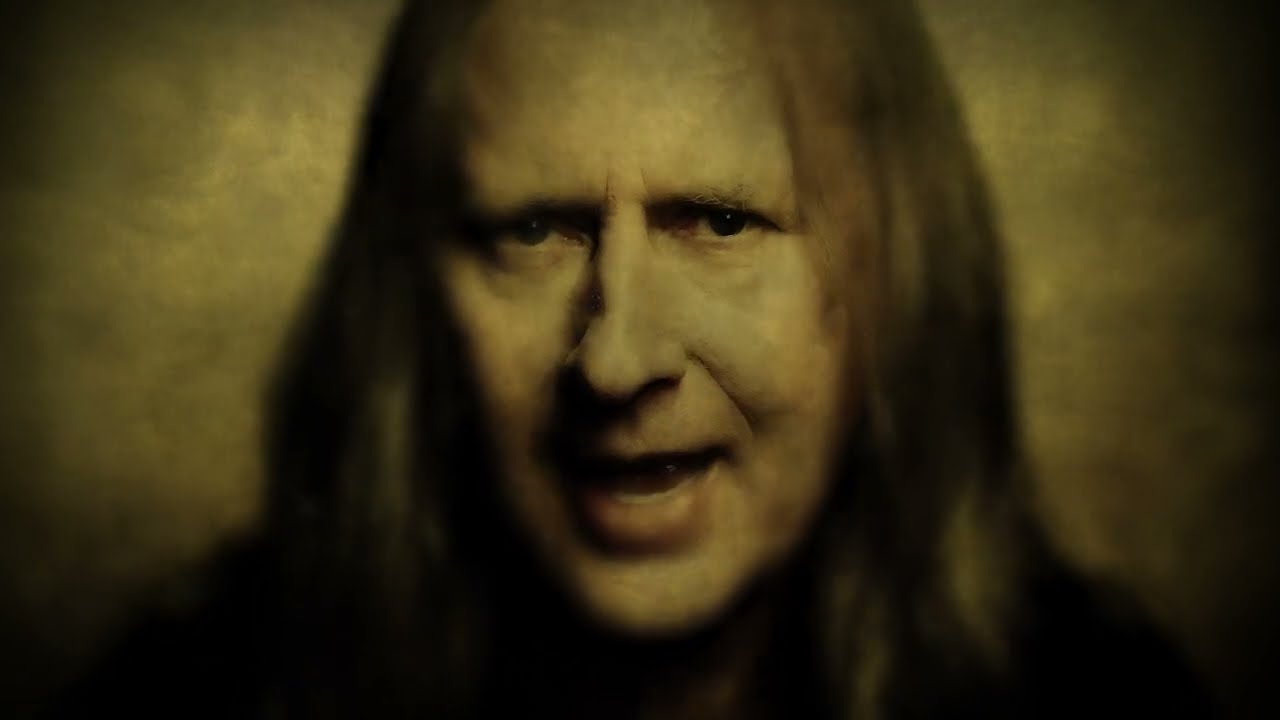

Is Jerry Cantrell still committed to Alice in Chains? You might well wonder. It's been six years since Alice in Chains released 2018’s Rainier Fog. In the interim, Cantrell has issued two solo albums: 2021's Brighten and, his new album, I Want Blood, released October 18.

As the grunge icon tells Guitar Player, he was “fired up” by the success of Brighten — his first solo effort since 2002's Degradation Trip — and was eager to follow it up.

“I went through making Brighten and then touring it, and I hadn't gotten to do that in almost 20 years,” he explains. “That's a good chunk of time in a life, you know? So I was really fired up about the experience, and once it was over, I still felt inspired, and that I hadn't completed the creative cycle that I was in. So that's why we now have I Want Blood.”

Despite that, the grunge icon tells Guitar Player his commitment to Alice In Chains remains strong. The group broke up in 2002, following singer Layne Staley's death from a drug overdose, but Cantrell reformed the band for 2009’s Black Gives Way to Blue.

"Obviously, it’s no secret where my loyalty lies, and that’s with the band," he says. "I started Alice in Chains in Seattle in ‘87, and I remain committed to it.

“But I did have a period where we weren't doing a whole lot, and I was able to make [his 1998 solo debut] Boggy Depot and Degradation Trip. I kind of did those back-to-back over a period of a couple of years.”

As for I Want Blood, Cantrell acknowledges it’s “a hard title, a punch,” but says the meaning behind the phrase is not as violent as it sounds.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“The title track is a celebration of your life and your time here,” he explains. “It’s written as if you were facing off in a boxing ring with time, and time is basically saying to you, ‘Come on, what d’ya got? I want blood. I want your best.’ ”

It's an apt metaphor for how Cantrell approached the making of the album. A solid three-decades-plus into his recording career, the singer and guitarist has amassed an imposing and influential body of work, both with Alice in Chains and on his own. Now 58, Cantrell is hardly resting on his laurels. He has described himself as operating at the “top of his capacity” during the writing and recording of I Want Blood, and it’s evident in the final product. From the pile-driving pull-off riff that kicks off opener and first single “Vilified,” to the psych-tinged, harmony-laden “Afterglow,” the storming, punky title track to the Sabbathy “Throw Me a Line,” and the grungy “Echoes of Laughter," I Want Blood is a diverse and dynamic collection.

It’s also exceedingly heavy, even for Cantrell. Especially in the wake of the uncharacteristically sunny Brighten. “I like to think I've written some music in the past that has some weight to it, but this one has some real fire,” he says.

To help stoke that fire, Cantrell was joined on the record by a host of friends and past collaborators, including bassists Duff McKagan (Guns N’ Roses) and Robert Trujillo (Metallica), drummers Gil Sharone (Marilyn Manson) and Mike Bordin (Faith No More, Ozzy Osbourne), background vocalist Greg Puciato (ex-Dillinger Escape Plan), composer Tyler Bates, producer Joe Barresi (Tool, Melvins) and others. “They’re my extended family,” Cantrell says. “And on top of being people that I care about deeply on a personal level, they're inspiring fucking musicians who have been in and worked with some of my favorite bands in the world.”

Which, in his opinion, are the only people sort of people he’d want to work with outside of Alice in Chains. “If I’m going to do something like this, I’m going to call on the musicians I admire and that I respect,” he says. “Because making a record is a long commitment of time and energy. But when you come out the other side with a record like I Want Blood, it's worth every second.”

Cantrell laughs. “There’s an old joke of, ‘I became a guitar player so I could play in a rock band and not have to have a job.’ And this has turned out to be, like, the hardest-working job I ever could have taken. But knowing that you created your own lane, and that you followed your dream and that it worked? That's a fucking beautiful thing.”

A real standout moment on the new record is the title track, which is a more uptempo, hard-driving type of rock song than we tend to hear from you.

It has a little bit of a punk kind of edge to it, a little kind of’ 80s new-wave vibe to it, especially in the chorus. Maybe even Cure-ish. And it was one of the earlier ones that came into being. The main figure is actually something I've had kicking around for a couple of years, but just never found a place for it to exist. When I dug it up during the writing process and tried it out, I was able to come up with a middle section and then find a good chorus for it. And I just really liked where it was going. So then I start thinking about, Who's gonna play on it? And it was a no-brainer to ask Mike Bordin and Duff. Because Duff's got that hard punk-rock flavor. Mike does, too, and also with a weirdo flavor mixed in there, which was perfect for the song. So the three of us together made the sound.

On the other end of the spectrum, the closing song, “It Comes,” encapsulates something that is both characteristic and unique to your songwriting, which is the ability to craft these incredibly slow, heavy tracks that move at a glacial pace, and yet are completely engrossing and enveloping. It’s not an easy thing to do.

Well, thank you for saying that. And I agree, it's not easy to keep people engaged and enthralled in a slower-paced, brooding kind of thing. But that's the challenge. As for what draws me to that sort of song? I don't know, really. There's so many elements that make up me, musically. I hear a lot of Floyd in that song. Sabbath. Zeppelin could be in there, too. There's a lot of those elements. And actually, if you at my discography both with Alice and on my own, the last song on a record often takes that sort of a shape of being a big, epic tune, you know? Elton John used to do that with his ending tracks, too, where they made a statement. I think it's important to have a good closing chapter to the book, so to speak.

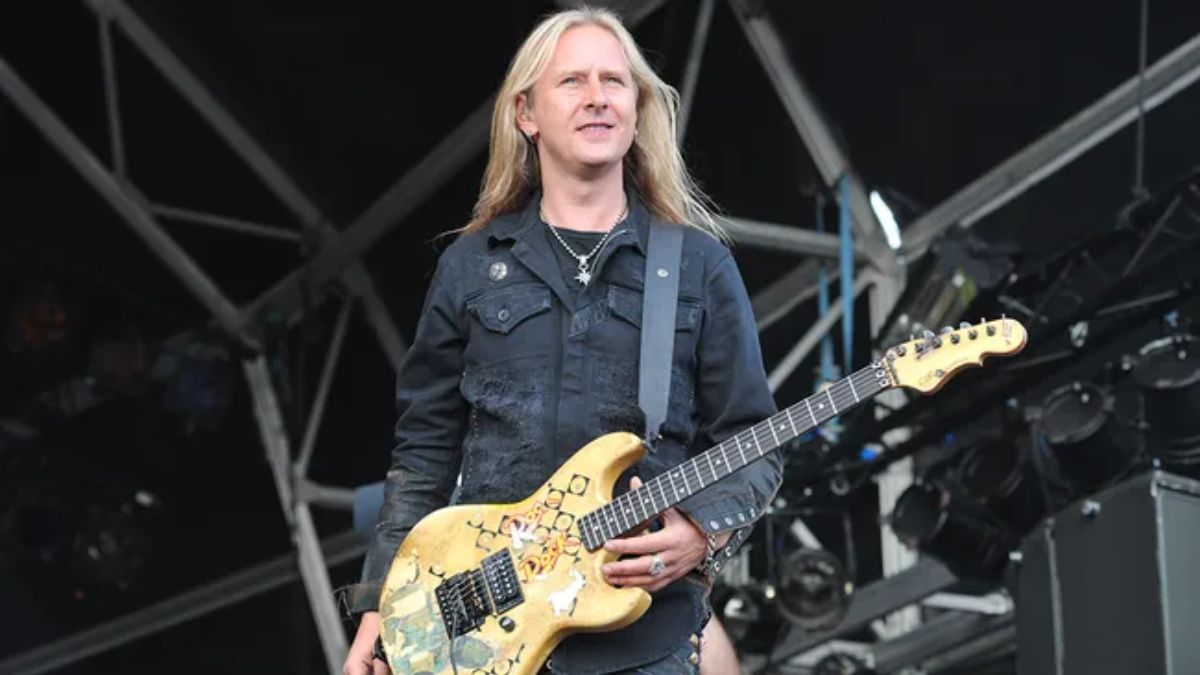

Gear-wise, what were your main guitars in the studio this time?

Pretty similar to what I always use. The core is always the two OG G&Ls – “Blue Dress” and “No War.” And then the “D Trip” Les Paul. That’s the cornerstone of my sound – the G&Ls blended with a Les Paul, and that Les Paul in particular. And you know, I've got a bunch of different G&Ls too, but they just don't sound as good as the two old ones, the ’84 Rampages.

And then, of course, there's a bunch of other stuff peppered in there – Vs and SG’s and Juniors… I think we even used an Ibanez Iceman on a track. And there was also a lot of baritone. Cesar [Gueikian, CEO and president] from Gibson made me a really great one before I jumped onboard with those guys [in 2021, Cantrell collaborated with Gibson on the Jerry Cantrell “Wino” Les Paul Custom]. He gave me this cool, kind of flat-black Explorer baritone that's just a monster. So that’s on there, too.

How about amps and pedals?

Well of course I’m using the Friedman double J’s [Cantrell’s signature Friedman JJ amp model]. But we also leaned heavily on some of my old gear. We went back to the Bogner Fish, which, Reinhold [Bogner, founder] got in there and took a look at my head because I wanted him to make sure it was ready to go. And he was like, “I don't wanna mess with this amp because it sounds better than mine!” So we used that Bogner Fish a ton for the main sound on the record. We also used a [Bogner] Snorkler, and a little bit of the Rockman blended in, too, with all of it. That's kind of similar to the Jerden setup, like when we did Facelift and Dirt [Cantrell is referring to producer Dave Jerden, who helmed both Alice in Chains records]. And again, with a whole bunch of other stuff peppered in there for flavor.

As for pedals, we used a ton of effects. We really leaned on the Cry Baby and the talk boxes quite a bit. And there's all sorts of fun old pedals and stuff – Rotovibes and phasers and delays… you name it. But one of the things that I'd never played before, and you can hear it on “Vilified” and a few other things, is the Jeff Beck talk box. [Cantrell is referencing the Kustom “The Bag”-style talk box that Beck used in the '70s.] I'd never really messed around with one of those before – I've just used the old box-on-the-floor-with-a-tube-coming-up-the-mic kind of talk box. But this one was interesting, because it's got a strap, and it kind of hangs under your arm like a bag. And the tube is much smaller, with a little tip on it for you to kind of put between your teeth. And it's just really expressive. I call it the bodabag, because when we were kids, we had these things that were like a skin, and you’d put some real shitty liquor and some Hawaiian Punch and whatever else in, mix it up, and then you'd sneak it into concerts. We called them bodabags. [laughs] This talk box looks like that.

You mentioned your “D Trip” Les Paul earlier, which is famous for having a really cool custom burn pattern on the body. How did you create that?

With a torch. That guitar, I think it's like a ‘94 or ‘95 Les Paul that was basically a reissue of an Eighties model. I don't know what the lacquer was that they used on it, but there was a show when I was a kid called Bonanza, and the show started with a map, and the map lights on fire in the middle and it starts burning fast out to the edges. The particular lacquer that Gibson used on this guitar is super-flammable, and it ran like that. When I lit it, I had to blow it out instantly to get that perfect burn. And there's a couple spots on the back, where I was trying to burn in the phrase “D Trip” [in reference to Cantrell’s solo album, Degradation Trip] where it got a little out of control. [laughs] It was really labor-intensive, but it came out great. That Les Paul is the one that’s the most well-known, and it’s the one I play the most. It's on every record since I got it.

Any idea what comes next?

[laughs] I do not. I'm just busy living and breathing this one. I'm gonna live this for the next year, and then I'll probably go home and crash for about a month, and then I'll see what's up next. Maybe I’ll go torch some guitars. Who knows?

Rich is the co-author of the best-selling Nöthin' But a Good Time: The Uncensored History of the '80s Hard Rock Explosion. He is also a recording and performing musician, and a former editor of Guitar World magazine and executive editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine. He has authored several additional books, among them Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, the companion to the documentary of the same name.