Translate Pentatonic Blues and Rock Licks into Swinging Jazz Licks

Despite their vastly different musical approaches, rock licks are more similar to jazz licks than you might think.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Most jazz styles revolve around the swing feel - a triplet-based interpretation of eighth-note rhythms. This bouncy feel is contrary to the even-eighth notes of traditional rock.

In swing jazz, though, although a tune’s lead sheet may appear to have a straight eighth-note melody, its upbeats - the “and” of each beat - are actually felt at a slightly later point than those of standard eighths like the first and last notes of triplets (counted “one-uh-let, two-uh-let, three-uh-let, four-uh-let”).

Add an accent on each upbeat and play slightly behind the beat, and you’ll be on your way to swinging.

Turning Pentatonic Rock and Blues Licks Into Jazz Licks

You can translate many pentatonic blues and rock licks into jazz licks simply by changing their feel and adjusting your technique.

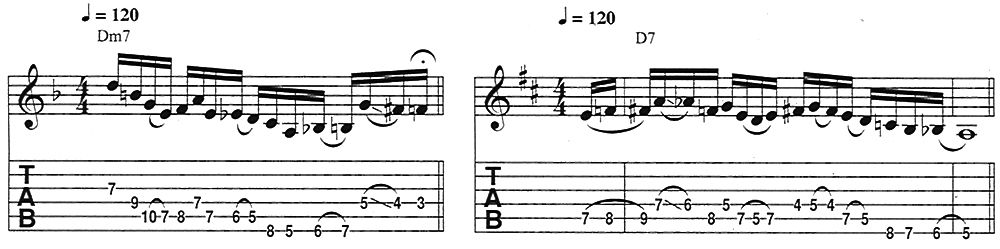

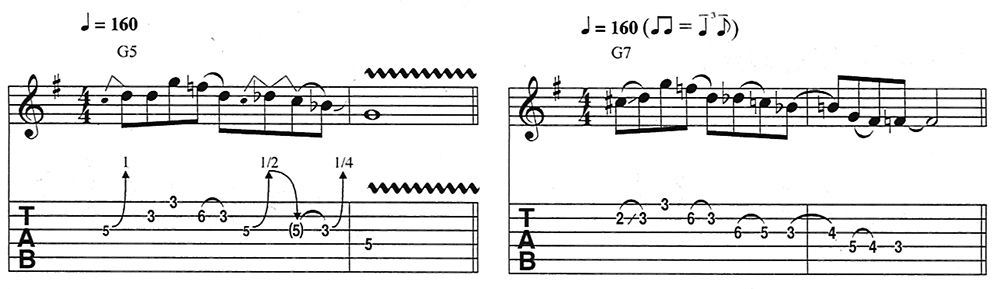

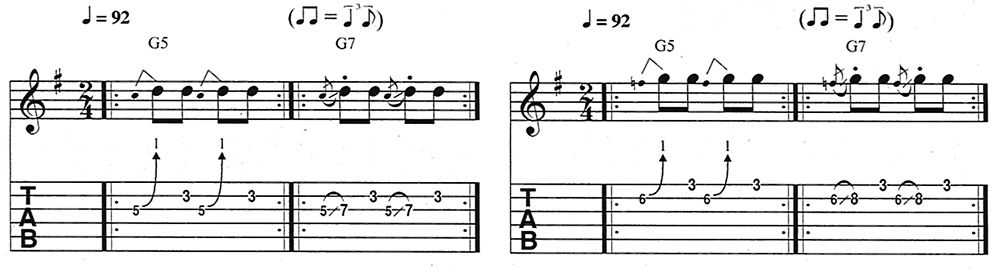

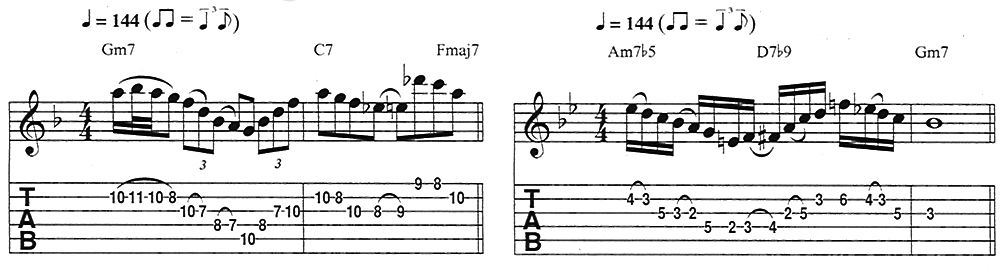

For example, to tweak the G minor pentatonic (G-Bb-C-D-F) rock lick in Figure 1A into a bop line in Figure 1B, play with a jazzy tone, replace bends with slides and add a swing feel.

Of key importance to this transformation is the replacement of the rock lick’s 1/4-step bend from Bb (3rd fret, 3rd string) with a legato slide to B (4th fret, 3rd string), the 3rd of the accompanying G7.

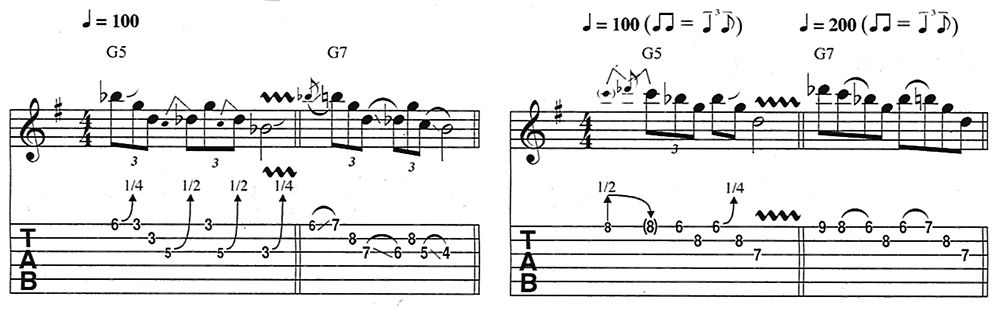

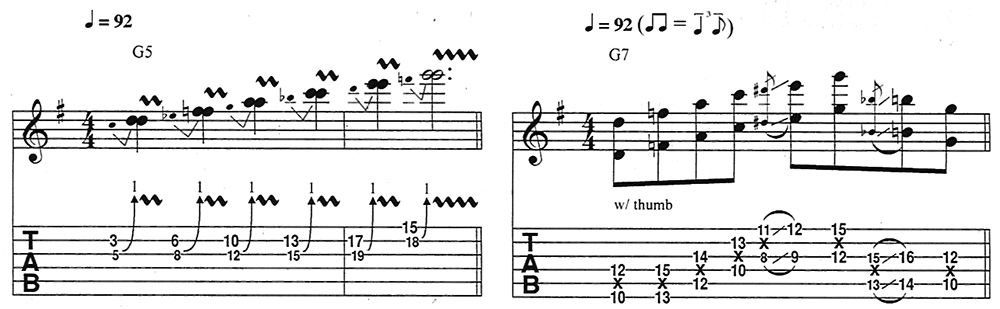

Figures 2A–D illustrate additional rock licks and their jazzy counterparts.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Technique Dos and Don'ts

As an addendum to the previous section, here’s an overview of the dos and don’ts of straight-ahead jazz playing.

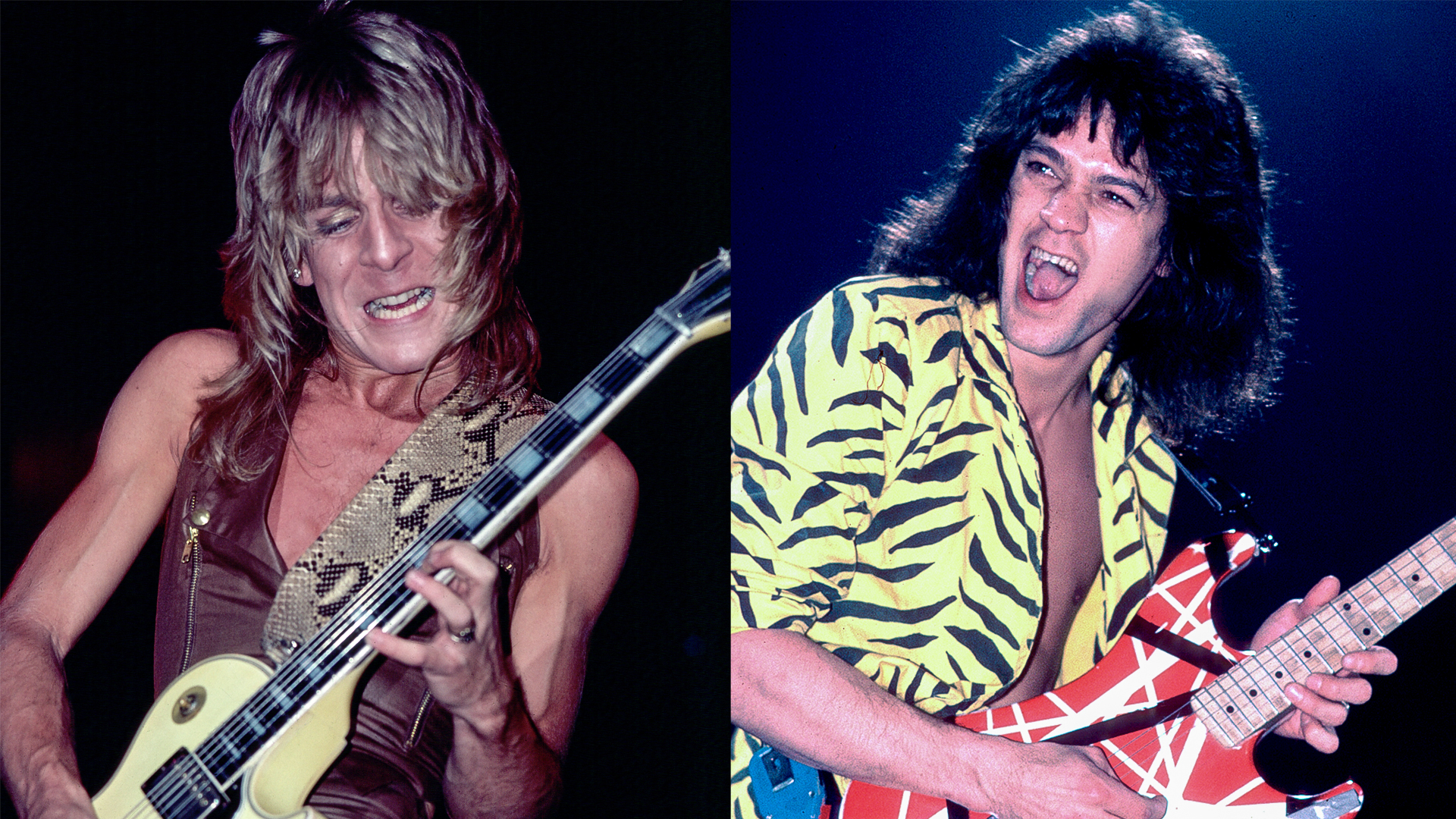

Typically, jazz guitarists don’t bend their strings much. Don’t be afraid to do it, but note that in the work of top-notch stylists like Charlie Christian, Wes Montgomery and Joe Pass, bends are rare; slides are used in their place.

In Figures 3A–D, time-honored blues and rock bends have been replaced with slides. Vibrato-inflected single notes are also uncommon in jazz guitar. If you hear this technique, it’s usually subtle, with the pitch wavering no more than a half the result of side-to-side “violin-style” vibrato.

On the contrary, other rock techniques translate to jazz quite nicely. Octaves can effectively thicken up a single-note line.

Figures 4A–B compare a rock-flavored unison-bend line with a jazzy, octave-fueled variation. Try playing octaves by brushing your strings with the fleshy part of your pick hand’s thumb.

Chords, too, are often strummed in this fashion, or plucked fingerstyle. Using economy or sweep picking for your arpeggios also gets a thumbs-up in jazz.

Signature Licks Of Jazz Guitar Greats For Further Study

By studying the lines of jazz guitar greats, you’ll get an appreciation for the diversity of melodies that exist in ii–V territory. In addition, your vocabulary will grow by leaps and bounds.

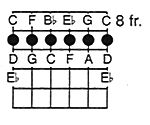

Charlie Christian, who rose to fame as a member of Benny Goodman’s band, was among the first jazz cats to cop horn lines on guitar. The “box” shape in Figure 5A is home for many of Christian’s dominant licks, such as the one in Figure 5B.

Wes Montgomery, who got his professional start playing Christian’s solos note for note, used his thumb instead of a pick, as in Figure 6A.

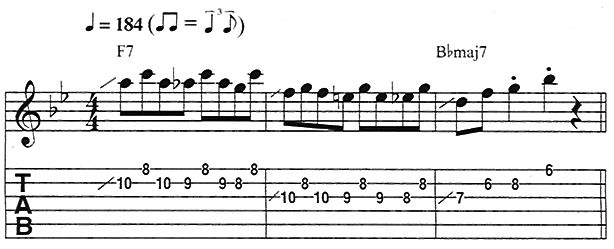

Joe Pass upped the bar for technique with double-time lines (playing steady 16ths over a swing-8ths groove) like the ii–V7–i in Figure 6B.

Pat Martino specializes in chromatic approaches within the realm of Dorian [Figure 7A], and Pat Metheny possesses a unique legato touch [Figure 7B].