Thinking Outside the Blues Box

Learn how to break free from blues clichés.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

One great way to escape the so-called limitations of blues and pentatonic scales is to blend your existing vocabulary of blues clichés with new ideas, derived from melodic substitutions. Take, for example, a 12-bar blues progression in the key of G. You’re probably already aware that its inherent I, IV and V chords (G7, C7 and D7, or G9, C9 and D9 extensions) can be navigated using licks built from combinations of the G minor pentatonic, major pentatonic and blues scales.

Granted, there are countless ways to utilize these scales to produce both clichéd and non-clichéd electric guitar licks. (It’s always interesting when someone claims to be “stuck in a rut” with pentatonic and blues scales!) However, substituting melodic lines drawn from other scales can open up endless new avenues for musical exploration and exploitation. To that end, we’re going to look at how to treat each chord individually by approaching it with a relative minor mode.

Mix in Mixolydian

Here’s the theory behind the concept: Any harmonized major scale produces only one dominant seven chord built from its fifth scale step – G7 in the key of C, C7 in the key of F, D7 in the key of G and so forth – which also provides the root of its corresponding Mixolydian mode (think major scale with a b7).

So, theoretically, a 12-bar blues in G is actually in three different major keys – C for the I chord, F for the IV chord and G for the V chord. Now we could stop here and simply use each chord’s Mixolydian mode as a melodic source – G Mixolydian for G7 or G9, C Mixolydian for C7 or C9 and D Mixolydian for D7 or D9 – but let’s take it a step further and convert each dominant seven chord to its diatonically related IIm7 chord rooted either a fifth above or a fourth below.

The idea is not to substitute the chords themselves – we’ll still be playing over G9, C9 and D9 – but to think Dm7 (the IIm7 chord in the key of C) for G9, Gm7 (the IIm7 chord in F) for C9 and Am7 (the IIm7 chord in G) for D9. It may sound confusing on paper, but the shape-driven architecture of chords and scales on the guitar makes applying these subs to the fingerboard a breeze. You’ll see.

A Dose of Dorian

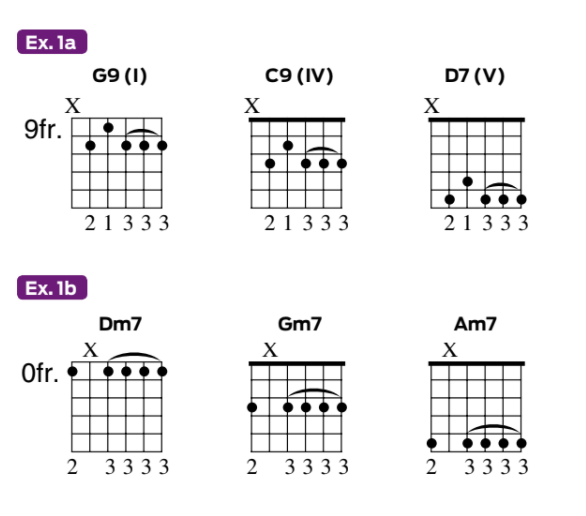

Start by playing a 12-bar blues in G using only the G9 (I), C9 (IV) and D9 (V) chord shapes illustrated in Ex. 1a. Now compare these to their relative IIm7 chord shapes in Ex. 1b. Each pair of relative chords shares several common tones – you can easily spot a first-inversion Dm triad nestled in the top three notes of G9, a Gm triad sitting on top of C9 and an Am triad embedded in D9. (Tip: Omit the root of each ninth chord and you’ve got a relative IIm6 chord.)

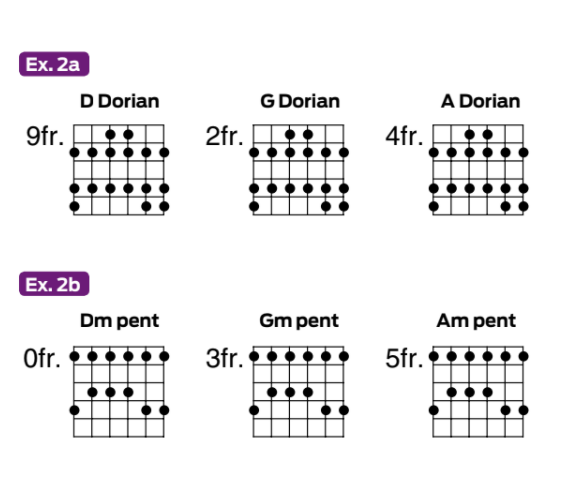

Next, we build three Dorian scales/modes (root, 2, b3, 4, 5, 6, b7) from the root of each minorseven chord, as shown in Ex. 2a. Play each ninth chord followed by its corresponding scale pattern – G9 for D Dorian, C9 for G Dorian and D9 for A Dorian – descending from its highest to lowest note (and vice versa) and dig the enhanced blues tonality. You can also reduce each Dorian pattern to a very familiar minor pentatonic “blues box” rooted a fifth above each ninth chord by omitting its 2 and 6, as shown in Ex. 2b.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

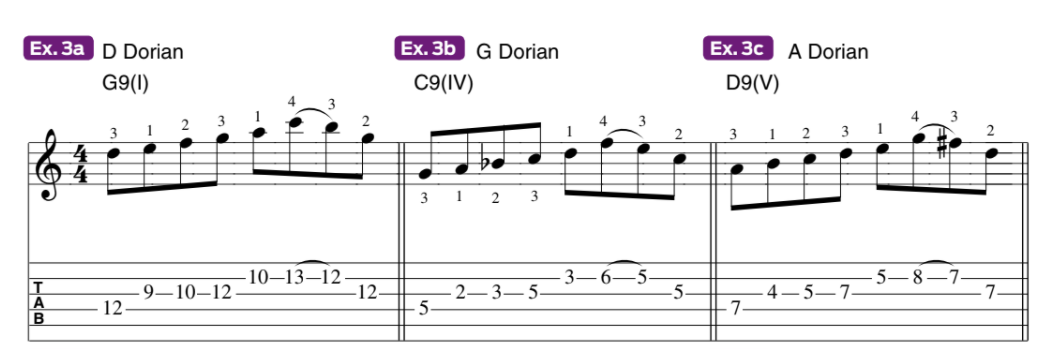

Examples 3a–c feature a short D Dorian melodic motif applied first to G9, then transposed to G Dorian and A Dorian to cover C9 and D9, respectively. Notice how each line starts on the 5 and ends on the root of each chord. Try dropping these into select measures of a 12-bar G blues while filling in around them with your existing vocabulary of blues licks.

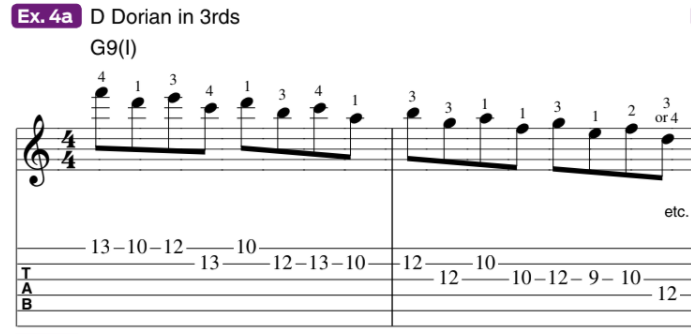

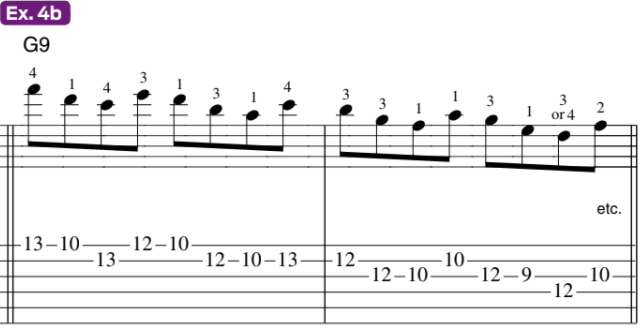

Applying intervallic and melodic sequences to each substituted Dorian pattern immediately transports you out of cliché-ville. Ex. 4a reorganizes the D Dorian pattern from Ex. 2a into descending diatonic third intervals, while Ex. 4b reverses the direction of every other pair of eighth notes on beats two and four. Play both sequences over G9. (Tip: Try reversing the order of eighth notes on beats one and three in either example.)

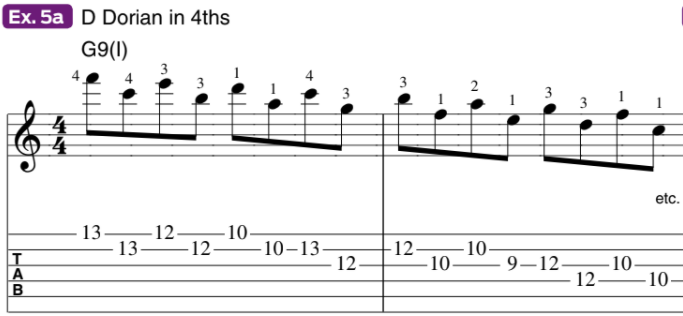

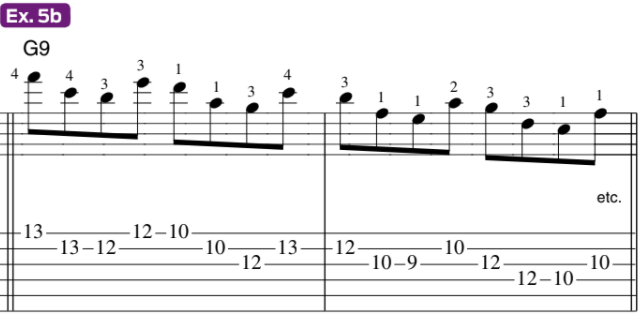

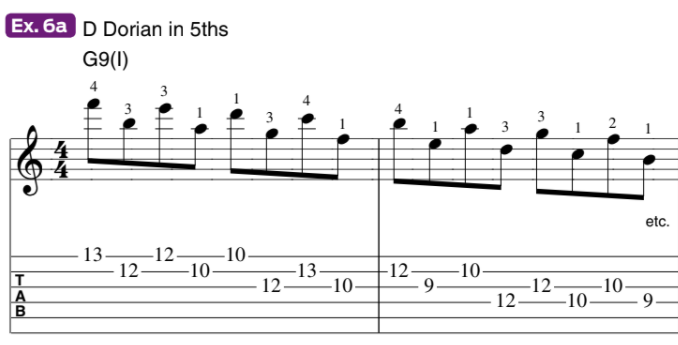

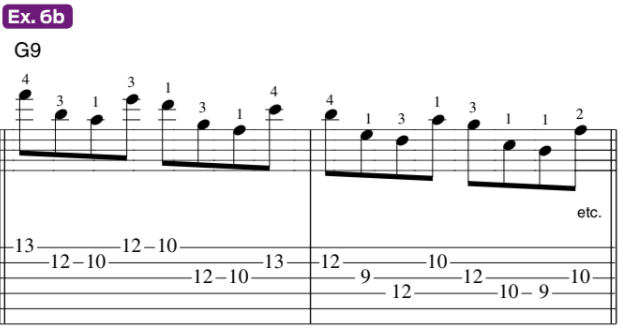

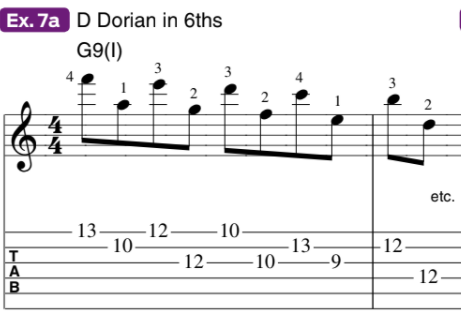

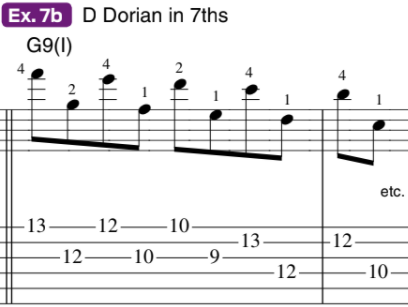

These and all other intervallic sequences can be transposed to G Dorian and A Dorian to cover the IV and V chords (C9 and D9). We continue with similar D Dorian sequences descending first in fourths (Examples 5a and 5b) and then in fifths (Examples 6a and 6b). After that, it’s onward to Ex. 7a’s descending sixths, Ex. 7b’s sevenths and Ex. 7c’s octaves, all of which require some additional assembly to complete.

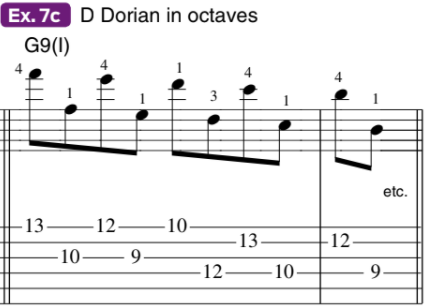

Though we won’t delve into rhythmic variations in much detail (that’s another lesson), Examples 8a–c present a few common rhythmic motifs as options. Applying each one to the previous intervallic sequences breaks you out of the straight-eighths mold and into less clichéd territory. Ex. 8d employs a 3/8 hemiola, via eighth-plus-quarter-note groupings that take three bars to recycle, while Ex. 8e utilizes 12/8 meter for a one-bar motif gleaned from Frank Zappa’s “King Kong.”

Combining Chromatic

It turns out you can add a chromatic passing tone to the Dorian and relative Mixolydian modes – a major 3 (F#) sandwiched between the 4 (G) and b3 (F) for D Dorian, which also functions as a 7 between the root and b7 for G Mixolydian – game on!

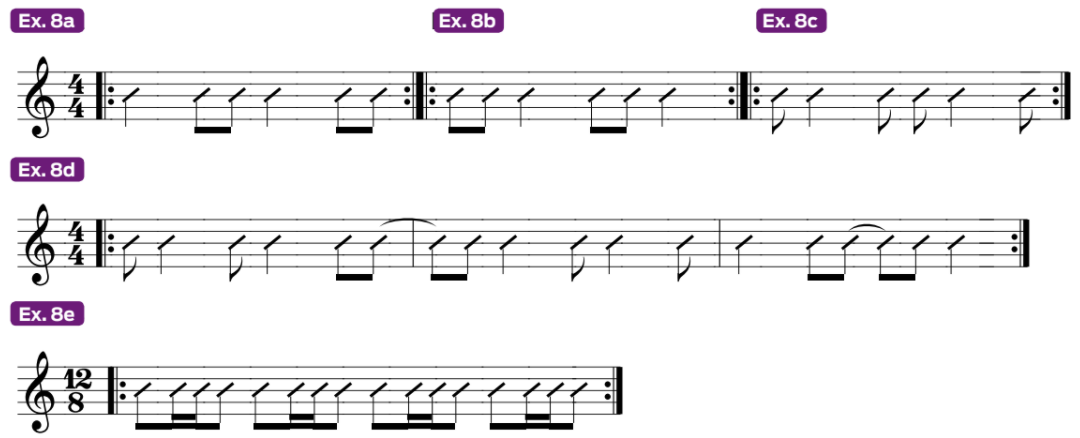

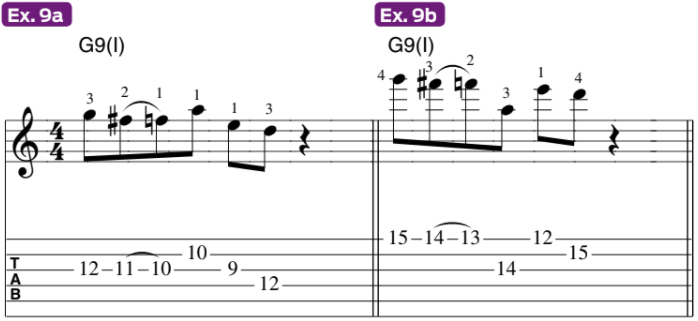

The pair of life-changing (for me) I-chord licks in Examples 9a and 9b demonstrates usage of what is sometimes called the D “Dorian+3,” or the G “jazz-blues scale.” It’s the same lick played in two different octaves, but Ex. 9b features an additional demonstration of octave displacement on the A note. Ex. 10a shows the pattern from which Ex. 9 originated.

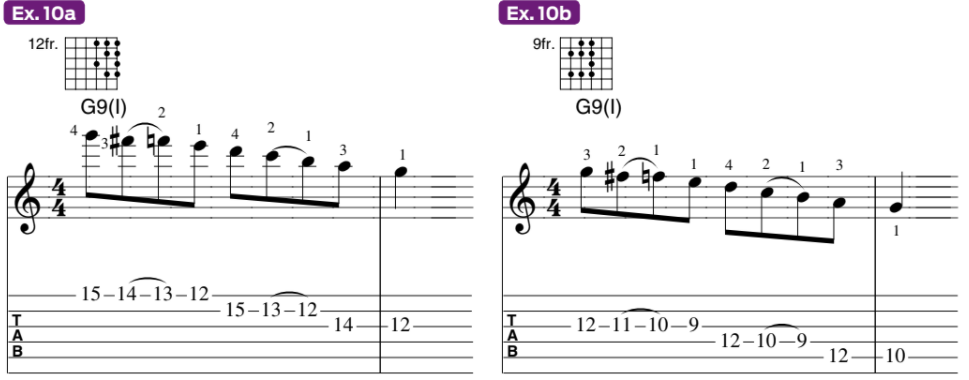

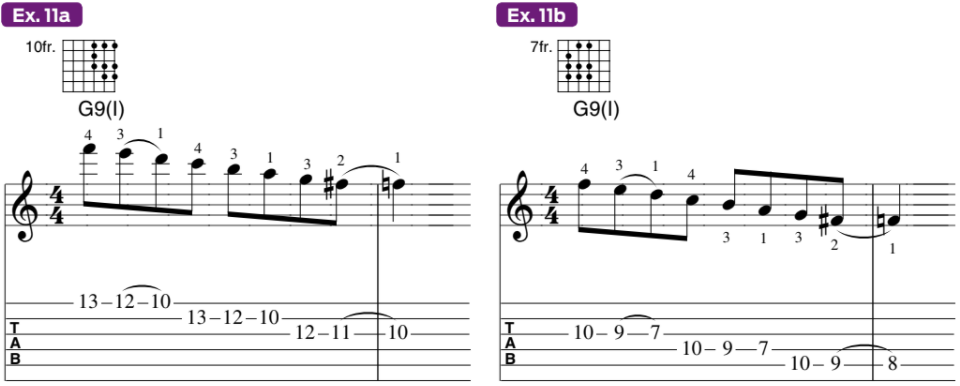

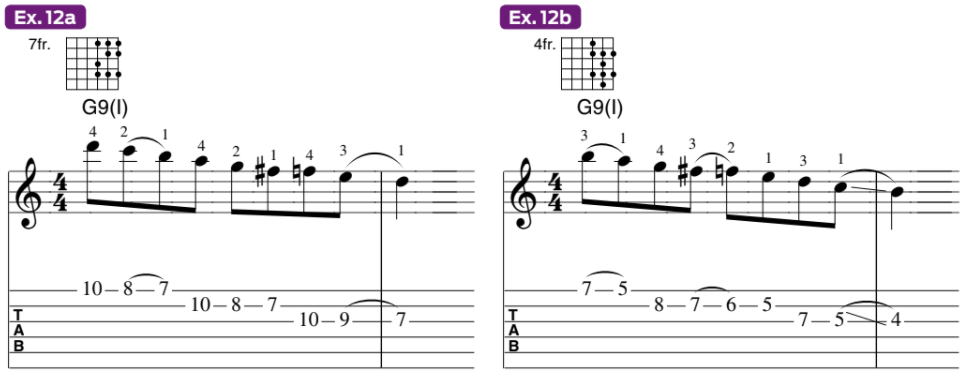

While the notes may be analyzed relative to Dm7, against G9 we’ve got, in descending order, the root, 7, b7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2 and root. Ex. 10b illustrates the same scale played one octave lower, where it can easily be connected to Ex. 10a. Ex. 11a and its octave-lower counterpart in Ex. 11b invert the same scale to start and end on F, the b7 of G9, and Examples 12a and 12b follow suit, starting and ending on G9’s 5 (D) and 3 (B), respectively.

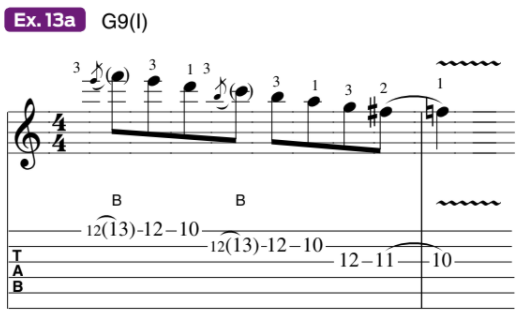

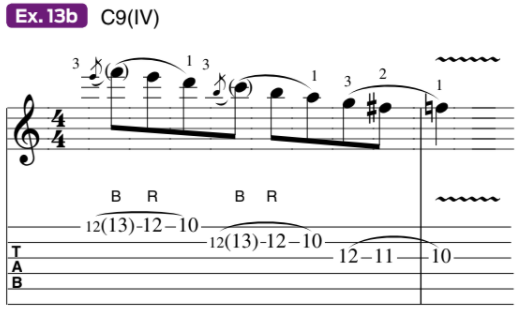

Remember that all four of these inverted scales can be transposed for application to C9 and D9. And don’t neglect your favorite blues phrasing techniques. String bends, hammer-ons, pull-offs and finger slides are applicable to all of the previous examples. The embellished scale runs in Examples 13a and 13b will get you on the right track.

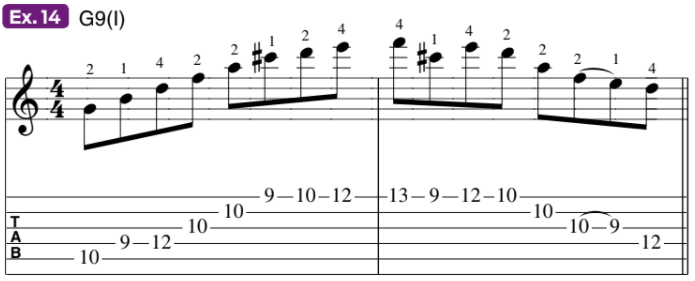

Finally, Ex. 14 reveals one of my all-time favorite altered-dominant licks pilfered long ago from a Ted Greene book. Though all of its notes except C# belong to D Dorian, I tend to think of this run as an ascending G9 arpeggio (G-B-D-F-A), followed by a G-based #4-5-6-b7-#4-6 motif (C#-D-E-F-C#-E), ending with a descending, D Dorian-based root-5-b3-2-root move (D-A-F-E-D). Transpose it to cover the IV and V chords, and watch the sparks fly!