Are You Missing Out On These Vital Techniques? Learn How Guitar Playing Evolved in the ‘90s in this Free Lesson

Embracing the ethos of blues-rock, early metal, ’70s soul and punk these tricks of the trade reinvigorated rock and could do the same for your own playing.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Musical evolution is complex and hardly linear, but it’s still remarkable to marvel at how decade-centric stylistic trends in popular music seemed to be in the 20th century.

Rock guitar in the ’80s was an arms race of flash and speedy, alternate-picked scalar runs. Digit-distending, fretboard-tapped arpeggios were de rigueur for any aspiring, high-coiffed six-string hero.

But as the ’90s got under way, a new aesthetic – one more tied to the ethos of blues-rock, early metal, ’70s soul and punk – began to emerge. Suddenly, fluorescent-pink Strat-bodied electric guitars with hot-rodded pickups and locking-nut tremolos were being traded in for Fender Jaguars, while digital rack-mount processors got swapped for Big Muff overdrives and wah-wahs.

Before you knew it, traditional tube amps, headstocks and a DIY anti-hero ethos were back in fashion.

Aside from being a mere retro nostalgia trip, ’90s guitar saw the emergence of several stylistic trends that have since become regular staples of the rock guitar lexicon.

For this lesson, let’s put on our favorite cargo shorts, flannel shirts and bucket hats and explore some of the playing techniques and musical approaches that characterized and defined the magic era that also gave the world Seinfeld, dial-up internet and reality TV.

NON-TERTIAN HARMONY

Essentially a fancy way of saying “chords not based on thirds,” non-tertian harmony became commonplace with ’90s strummers, whether they understood the theory behind them intellectually or instinctually.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

One especially popular harmonic move was to keep at least one common tone ringing among all the chords in a progression, resulting in the addition of exotic-sounding 9ths and 11ths to otherwise pedestrian open-chord grips.

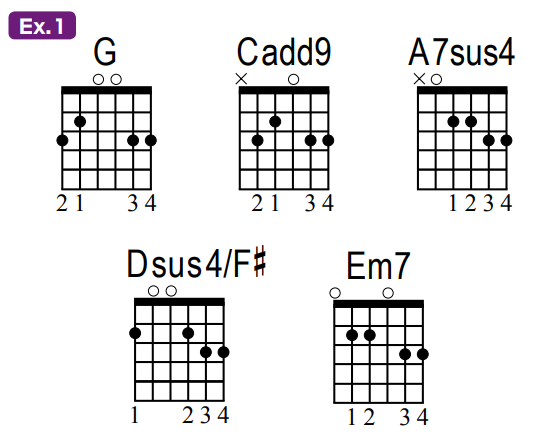

Play through the voicings illustrated in Ex. 1 and you’ll see that they are essentially your standard-issue coffee-house open fingerings but with the third and fourth fingers anchored at the third fret on the two highest strings, allowing the D and G notes to ring throughout.

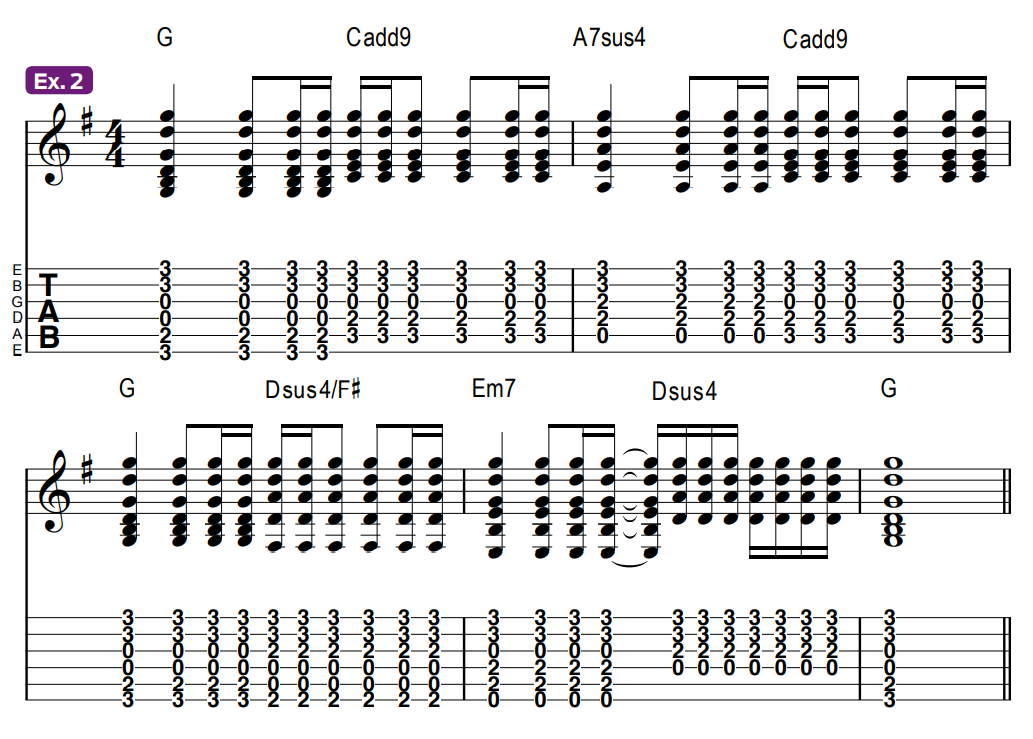

Strummed fervidly, as shown in Ex. 2, these voicings recall the jangly vibe of Oasis’s “Wonderwall,” and they also bring to mind Extreme’s “More Than Words” and “Closer to Fine” by the Indigo Girls.

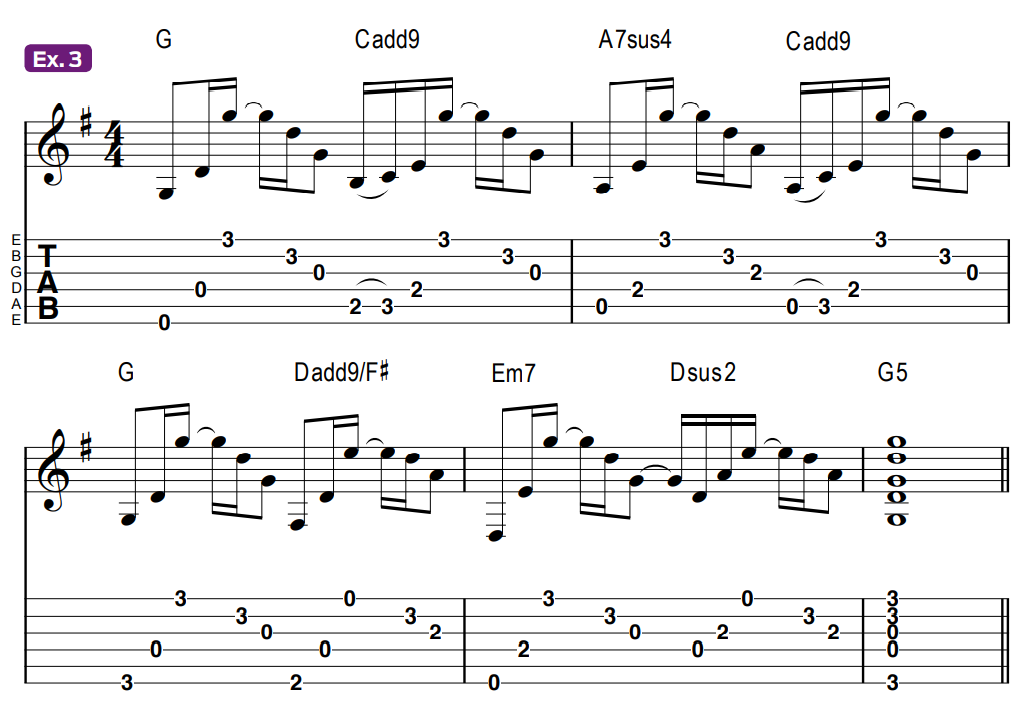

Try adding a spritely arpeggio pattern to the same chords, as in Ex. 3, to conjure the six-stringed mojo behind Green Day’s “Good Riddance (Time of Your Life)” and “Slide” by the Goo Goo Dolls.

DRONE STRINGS AND SLIDING OCTAVES

Thanks to a renewed reverence for the 1960s counterculture, a quasi-Middle Eastern influence started to creep back into rock music in the ’90s.

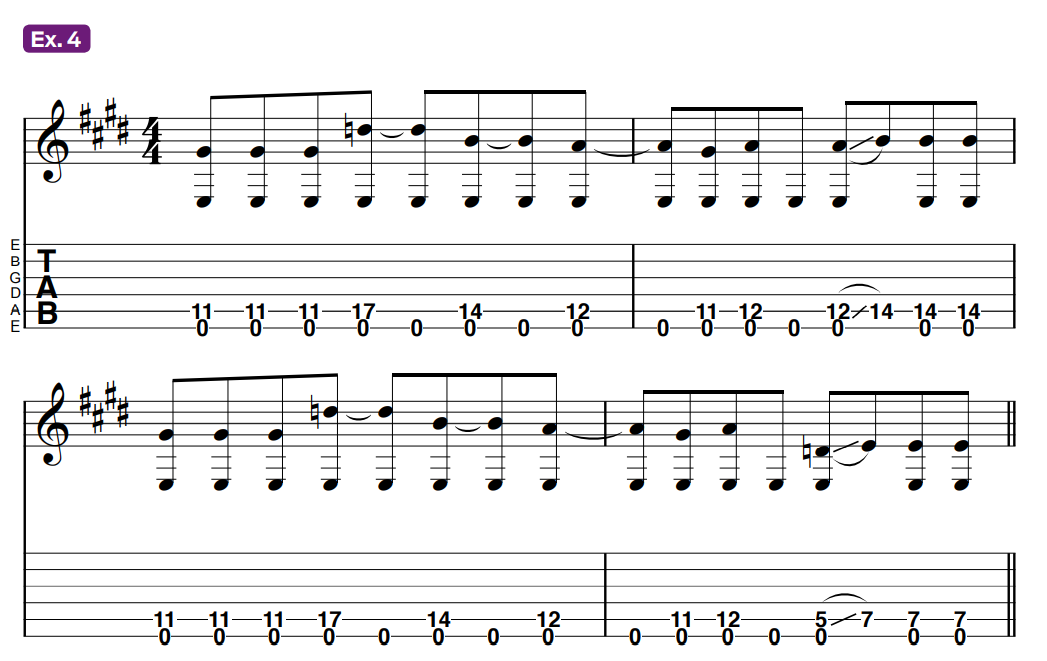

Raga-inspired, single-note modal melody lines played against open drone strings, as in Ex. 4, were employed to sculpt many a majestic riff, including Nirvana’s “All Apologies,” “Starla” by the Smashing Pumpkins and “Villains” by the Verve Pipe.

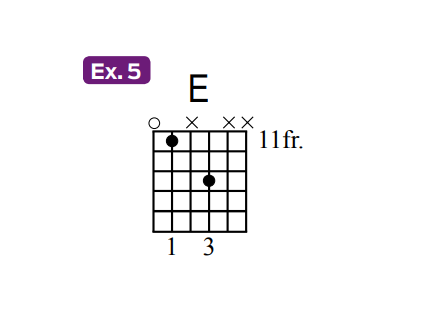

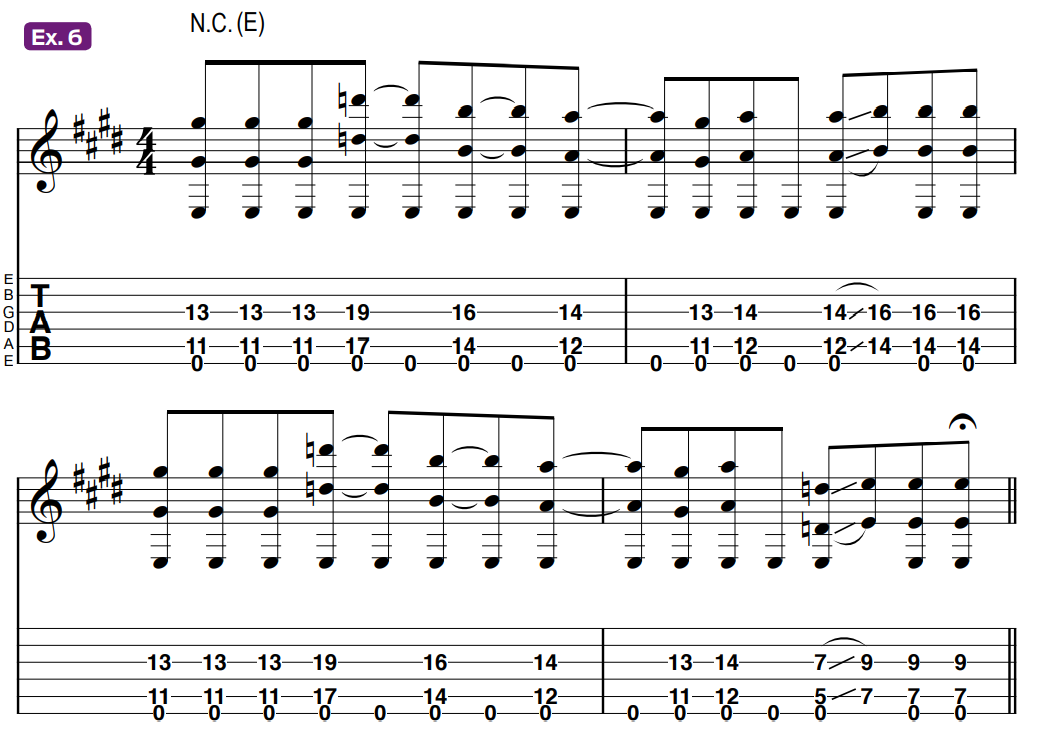

An expansion on this exotic technique often involved employing the sliding strummed octave shape illustrated in Ex. 5. Although originally adopted by jazz guitarists, most notably Wes Montgomery, as a way to thicken melodies, rock players began working the strummed octave shape into their riffs since it provided an expansive orchestral sound that also allowed for more melodic freedom than a basic root-fifth-octave power-chord voicing.

When forming this grip, lightly mute the unused D string with your first finger and the B and high E strings with your third or fourth fingers to prevent any unwanted open notes from ringing out, then try playing Ex. 6, an octave-against-drone-string melody not unlike those heard in the anthemic songs “Cherub Rock” by the Smashing Pumpkins and “My Hero” by the Foo Fighters.

POWER CHORDS WITH THE FIFTH IN THE BASS

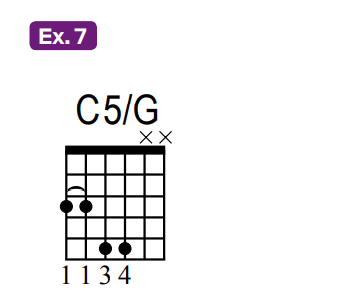

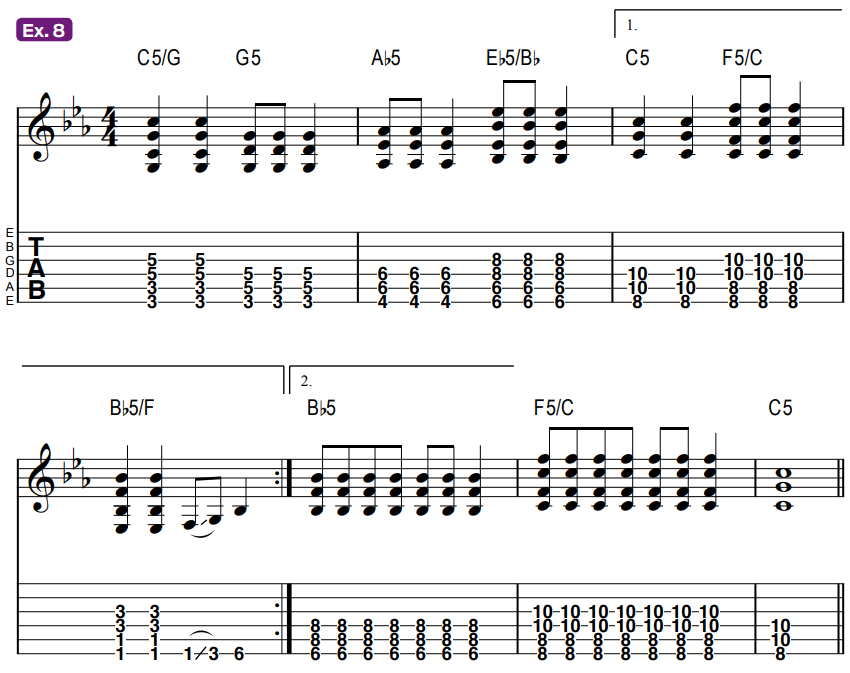

The Seattle grunge guitar sound often highlighted a fuzzy and deep low-end, and one way to achieve this low-register girth was to “over-barre” with the first finger when playing fifth-string-root power chords, essentially adding an extra fifth in the bass below the root, as illustrated with the C5/G chord grip in Ex.7.

Dropped into chord progressions where there would normally be a fifth-string-based root-position power chord, this second-inversion (fifth in the bass) voicing can add depth and resonance to a riff and produce a jarring yet desirable dissonance while staying completely diatonic to the song’s key.

Play through Ex. 8 then listen to the intro to Semisonic’s “Closing Time” or the chorus to “Buddy Holly” by Weezer to hear some fine fifth-in-the-bass fortitude.

DROP-D TUNING

Of all the go-to ’90s guitar techniques, perhaps none has been so widely appropriated as drop-D tuning – tuning the low-E string down a whole step to D.

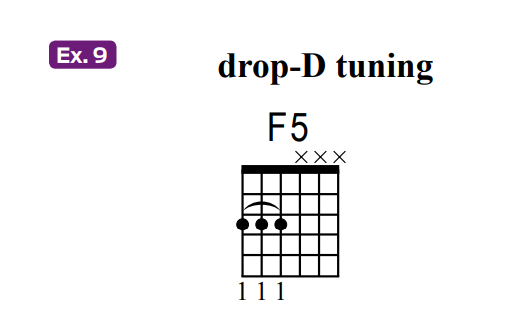

Guitarists have been employing this tuning for decades, most often in an acoustic fingerstyle context. It was Ty Tabor of King’s X who first began experimenting with it in a heavy-rock context and exploiting the fact that, by barring the bottom three strings, you could conveniently grab a one-finger root-fifth-octave barre chord, such as the F5 shown in Ex. 9, and, just as importantly, move it around quickly.

Aside from sounding massively deep and heavy, drop-D tuning allows guitarists to craft and perform rapid-fire chromatic powerchord riffs with the ease and facility of single-note riffs, and it was Tabor who first introduced this new vocabulary on King’s X’s 1988 debut album, Out of the Silent Planet.

Although King’s X remained largely a cult band, they were a direct influence on more mainstream acts like Soundgarden, Pearl Jam, Alice in Chains and Pantera, all of whom would adopt this tuning and its variants into their repertoire.

By the decade’s end, drop-D (and its downtuned variants drop-Db and drop-C) would arguably be as commonplace in hard rock and heavy metal as standard tuning.

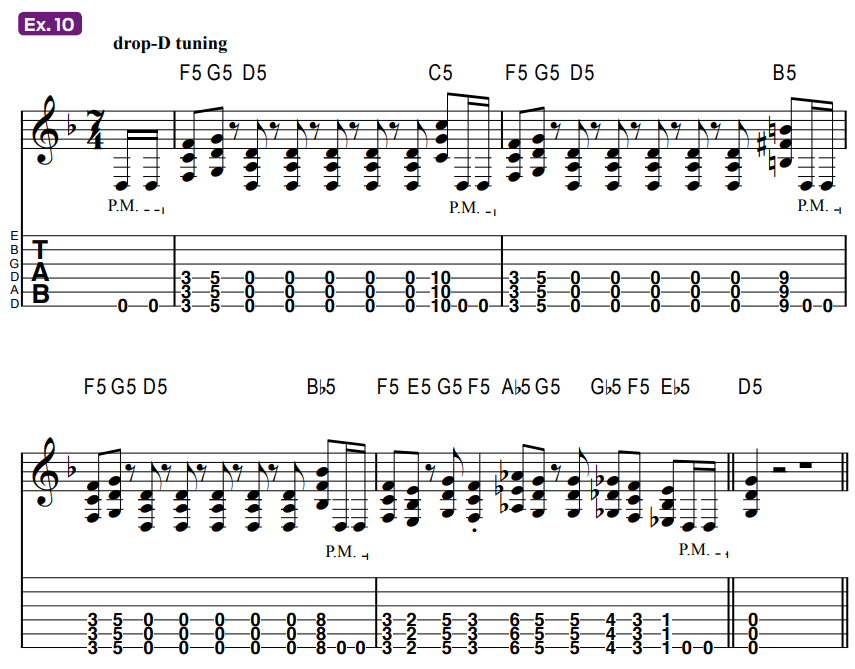

Ex. 10 is an example of the kind of syncopated and metrically sophisticated odd-metered drop-D grooves Soundgarden were known for, such as on their 1991 breakthrough hit “Outshined.”

For maximum jack-hammer effect, be sure to silence the open D5 chords on the upbeat of beats two through six, by quickly deadening the strings with a light touch of your fretting hand.

THE RISE OF FUNK METAL

Thanks to the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ and Living Colour’s reverence for all things George Clinton, combined with Rage Against the Machine’s and Faith No More’s experimentation with rap and hip-hop, the definition of what could be classified under the rubric of rock and metal greatly expanded during the ’90s.

Although some have eschewed the “funk-metal” moniker as a trend, suffice to say it was a daring and artistically fruitful cross-pollination of funk’s dense, syncopated rhythms and metal’s raw power.

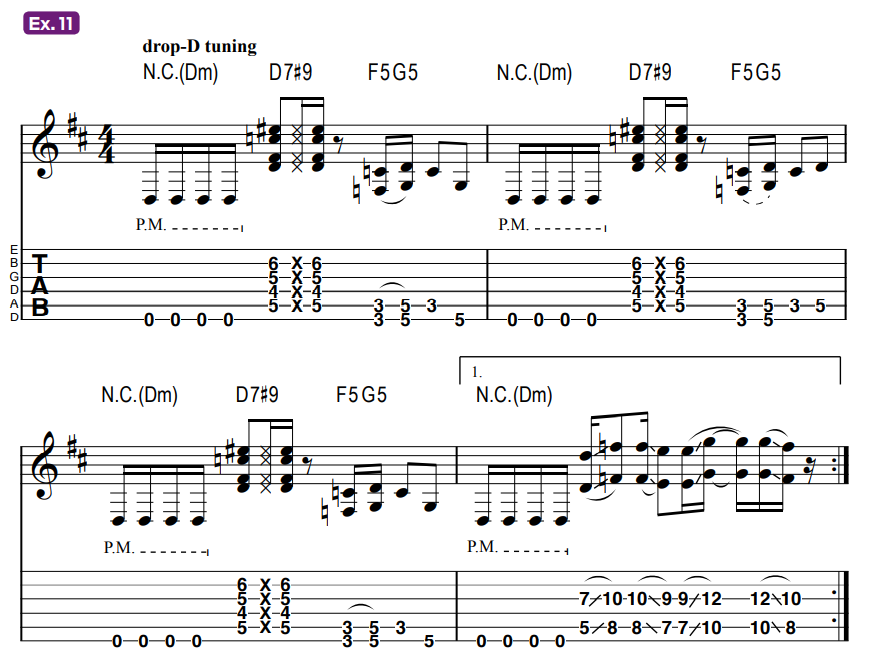

Ex. 11 brings to mind such RATM classics as “Wake Up” and “Freedom,” by combining drop-D power chord riff age, syncopated Hendrix-approved D7#9 chord stabs, a sliding octaves melody and a rapid 16th-note chromatic turnaround in the second ending.

MELODIC GUITAR SOLOS

When Robert “Waddy” Wachtel tracked the austere unison-bend guitar break to Steve Perry’s hit “Oh Sherrie” in 1984, there were some musicians who derided it for its simplicity. But think about it; The solo was effective and memorable. We bet you can sing it off the top of your head.

Fast-forward seven years to when Kurt Cobain cut the straightforward but powerful melodic solo on Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” and you’ll see how the taboo against restraint had been permanently smashed.

In fact, some of the decade’s most stellar lead guitar moments were steeped in the “less is more” ethos. John Frusciante’s break on the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ “Californication” and Dan Vickrey’s solo on Counting Crows’ “Goodnight Elisabeth” are two prime examples of effective melodicism.

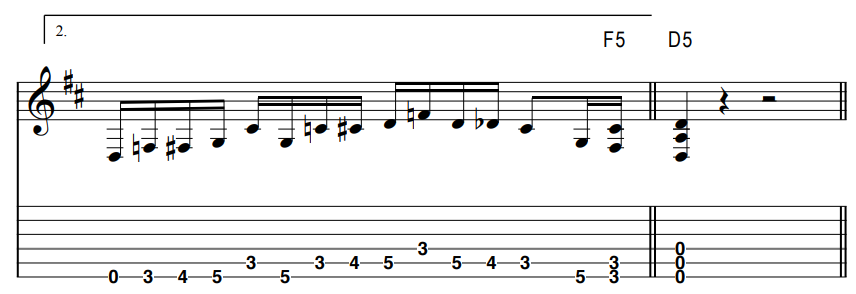

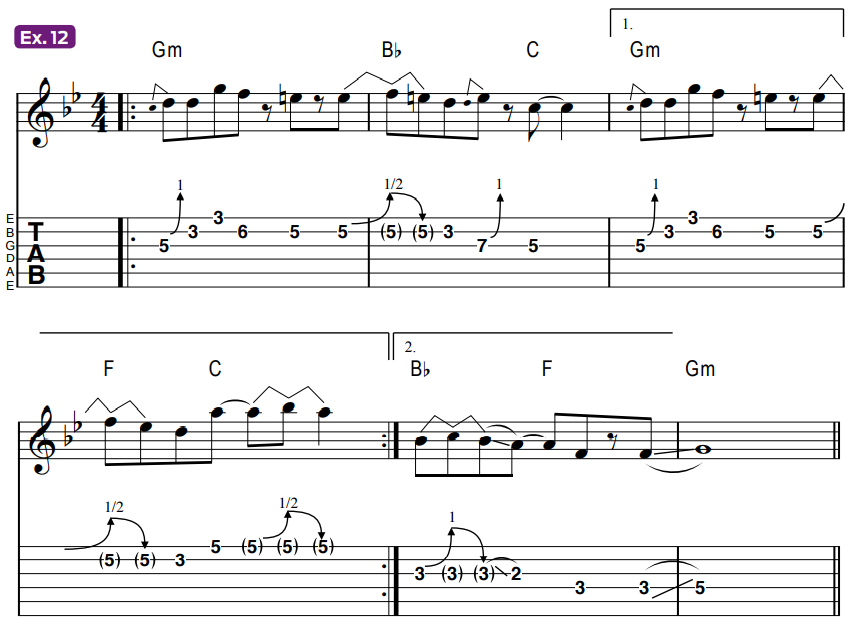

For Ex. 12, our final example, we’ve taken a chord progression loosely based on “Smells Like Teen Spirit” and added a melodic solo around a G Dorian (G A Bb C D E F) tonality. It’s very motif-based and relies on phrasing – particularly slides and bends – more than flash to get its point across.

Trends in music may come and go, but these popular ’90s guitar techniques remain a valuable part of rock’s language. Why not put them to work in your playing?