Amazing Phrasing: 10 Ways to Improve Your Solos

Put these techniques to work in your solos, and see—and hear—the difference they make.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

We all know a killer phrase when we hear one, but exactly how do you define what makes one phrase so much better than another? And how do you improve your own phrasing?

It’s not as hard as you might think. In this lesson, we’ll unlock the mysteries of phrasing by focusing on the three key aspects of a phrase: rhythm, harmony and melody. We’ll explore ways to diversify your rhythms, expand your harmonic vocabulary, and approach scales and patterns more melodically.

This three-pronged attack will help you develop your unique voice as a guitarist. The great players are all masters of the phrase, and there’s no reason you can’t master this elusive art too.

1. RHYTHMIC DISPLACEMENT AND SUPERIMPOSITION

Many players naturally start a phrase on a downbeat, often the first beat of a measure. But by simply taking that same figure and displacing it—shifting it so that it starts either before or after the beat—you can break up the rhythm of a phrase that, if not displaced, might sound a bit stiff.

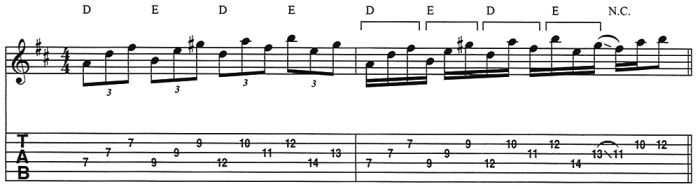

FIGURE 1 shows a pattern based on four 16h notes.

FIGURE 1

While the groups under brackets 1 and 2 begin on the beat, those under 3 and 4 are displaced by beginning the pattern on the second 16th note of the beat. This displacement causes the group in bracket 4 to go over the bar line, an effect that gives the phrase some forward momentum. Notice also that the notes under brackets 6 and 7 are displaced, but this time the pattern starts one 16th before the beat. Try these ideas with longer phrases and licks that you know, and practice them with a metronome or a drum pattern so that you can really feel the displacement.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

A related idea is rhythmic superimposition. For example, take a three-beat rhythmic phrase and play it in 4/4 time. If you repeat this phrase in 3/4, it will always begin on the first beat of every bar. But when played in 4/4, it starts earlier in each successive measure: the fourth beat of measure 1, the third beat of measure 3, and the second beat of measure 3. This type of three-beat pattern also goes over the bar line, but in order to hear the effect, you need to play it along with a 4/4 rhythm pattern. Otherwise it will likely sound as if it’s just a straightforward 3/4 lick.

2. RHYTHMIC GROUPINGS

When working with three-note groups, it’s easy for us to play them as triplets. And it’s equally easy to play four-note patterns, like the one in FIGURE 1, as 16th notes. Yet you can create interesting rhythmic feels by putting an odd-numbered note pattern into an even-numbered rhythm, or vice versa.

In the first bar of FIGURE 2, for example, triad arpeggios are played as triplets. But in the second bar, the same arpeggios are played as 16th notes. In the first bar, each three-note group starts on the beat, but when played as 16th notes, each group (indicated by brackets) begins on a different beat: the first 16th, the fourth 16th, the third, and the second, respectively. You can draw attention to the new grouping by accenting the first note of each group. And because each pattern begins on a different beat, the accent keeps shifting.

FIGURE 2

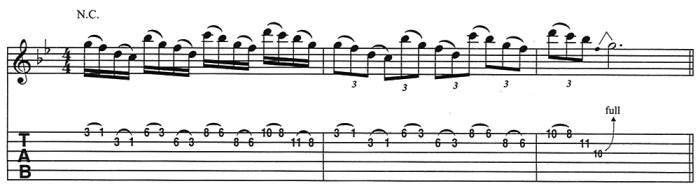

You can apply the same idea to four-note groups as well. In FIGURE 3, the pattern is first played as 16th notes and then as triplets. Experiment with other combinations, such as two- and five-note patterns played as triplets, five- and seven-note patterns played as 16th notes, or even five-note groups played in a rhythmic pattern, such as: 16th note, 16th note, 16th-note rest, 16th note—rests can be as important a part of any phrase as the notes. And, as always, you should develop these patterns into longer phrases by displacing some of the note groups and inserting rests and/or pitches with longer durations.

FIGURE 3

3. RHYTHMIC DIVERSITY

Two important and related aspects of sophisticated phrasing are the ability to move effortlessly between different rhythms and the ability to be free from basing all your solo rhythms on the underlying rhythmic unit of the song, be it an eighth-note, a 16th note or a shuffle groove (swung eighth notes). In other words, even if the song is a shuffle, you might want to switch back and forth between typical shuffle rhythms, such as triplets, and less-common ones, like straight eighth notes or 16th notes.

The exercise in FIGURE 4 can help you develop these abilities. In he first measure, you play two beats of eighth notes, followed by two beats of eighth-note triplets. In measure 2, you move from 16th notes to sextuplets and quintuplets. So the number of notes per beat per measure in the figure moves from two to three to four, and then from six to five.

FIGURE 4

Another and perhaps stranger way to come up with new rhythms might seem a little like math homework. Take a measure comprised entirely of eighth-note triplets and randomly remove some of the beats. Written out, a measure might first be counted like this: “one-and-a, two-and-a, three-and-a. four-and-a.” But after you take out some beats so that every quarter note has a different rhythmic unit, one possible result would be: “one-rest-a, rest-and-a, three-and-rest, four-and-a.” Do the same for a second measure, and you could end up with “rest-and-a, two-and-a, rest-and-rest, rest-and-a” [FIGURE 5]. Try this technique with other rhythms, such as quarter-note triplets or 16th notes. Although this might seem like an artificial way to create a phrase, you will definitely come up with some cool rhythms that you wouldn’t normally play. After working with these ideas, begin to add them into your solos. Eventually they’ll become a natural part of your playing.

FIGURE 5

4. CHROMATICISM

A chromatic note is simply any note that isn’t part of the key you’re playing in. On the guitar, these notes fall on the fret or frets between two consecutive notes in the scale. And because chromatic notes are outside the harmony, you can use them as a way to add some color and harmonic tension to your phrases.

The only thing to be careful of is emphasis. Skilled players tend to avoid staying on them for too long. Instead, they often use chromatic notes as passing notes—notes in between two consecutive scale tones—or as approach notes—notes a half step below or above a chord or scale tone.

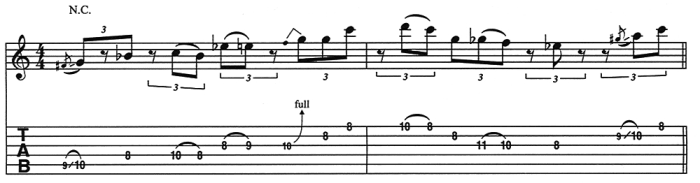

FIGURE 6 uses the A Dorian scale (A B C D E F# G), and the notes with an asterisk are chromatic notes. Notice how some of them are used as passing notes and others as approach notes. These notes represent only a few of the many possible chromatic notes around the Dorian scale in this position.

FIGURE 6

Another way to incorporate chromaticism into your playing is by using a note pattern based on the key you are soloing in and then repeating this pattern at a location where some or all of the notes are not in the key. This idea is the basis for the second measure in FIGURE 7. The notes under bracket 1 form a pattern that you move to two other frets (brackets 2 and 3) in the lick. The key to successfully employing this kind of chromaticism is resolution. As in FIGURE 7, you can start “inside” (on notes in the key or the scale), move “outside” (to notes not part of the harmony), and finally resolve back to either a chord- or scale-tone.

FIGURE 7

5. HYBRID SCALES

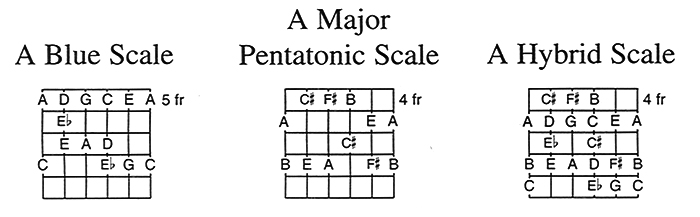

You can create a unique harmony source for phrases by combining notes from two different types of scales. When you do this, the result often doesn’t have an official name, but players call this kind of scale “hybrid.” Although you could form any two scales into a hybrid, the one we will focus on combines notes from the blues scale and the major pentatonic scale.

FIGURE 8 has three fingerings: the first is an A blues scale, the second is an A major pentatonic, and the third is the hybrid that results when these two are combined. This new scale has nine notes, which at first can make it seem a bit unwieldy. But remember when you improvise with this or any scale, there is no need to use all the notes. Targeting chord tones is a common improvisational tool to help lock in the harmony during your solo.

FIGURE 8

Look at the lick in FIGURE 9 for an example of how to interweave chord tones and other notes from a hybrid scale.

FIGURE 9

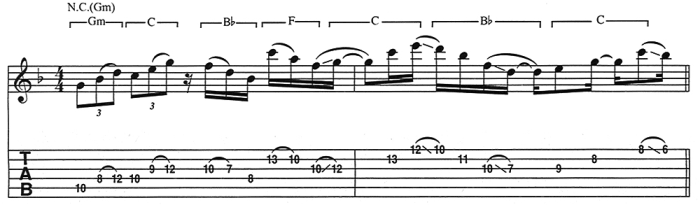

6. SUPERIMPOSED TRIADS

Another way to add harmonic interest to your solos is by building phases in which you superimpose multiple chords over a single chord. FIGURE 10 is a series of triad arpeggios based on the notes in a G Dorian scale (G A Bb C D F). The arpeggios—G minor, C major, Bb major and F major—are all played over one chord, Gm. The names in brackets identify the chords that are being superimposed. This same licks could be played over other chords from the key (F) as well. For instance, the lick would fit over a C7 or even a Dm chord. While it often works well to play three-note triads as triplets, it’s also good idea to break up the rhythm, as the lick in FIGURE 10 does.

FIGURE 10

FIGURE 11 employs a series of three- and four-note arpeggios of triads from the key of G: C, Bm, Am, G, F#˚, Em and D. You can play this lick over any of the chords it contains, but it works especially well over Em or Am. To add some rhythmic variety to this lick, practice it with a rhythmic exercise like the one in FIGURE 4.

FIGURE 11

7. MELODIC INTERVALS

Our phrasing can sound predictable when we solo with a limited number of intervals (the distance between two notes). When moving from note to note within a scale, we often play the note immediately above or below the one we just played. In most instances, this means that we end up using small intervals. This can make our solos sound like we’re just running up and down the scales.

An easy way to give your solos some interval variety is by using string skipping. With this technique, you skip over an adjacent string to get to a note on a nonadjacent sting.

In the first measure of FIGURE 12, the third note is played on the 5th string, while the fourth note is played on the 2nd string. Skipping the 4th string gives you an interval of a minor 6th. This lick uses a standard minor pentatonic fingering, but the technique works with any scale.

FIGURE 12

In FIGURE 13, we create larger intervals by shifting positions. The first measure of the phrase is partially based on the interval of a perfect 5th. The distance between the first and second notes (D and A) as well as between the second and third (A and E) is a perfect 5th. And the measure ends with another 5th, an A to E played one octave higher than the first A to E. The long slide at the end of the lick also gives you an atypical interval.

FIGURE 13

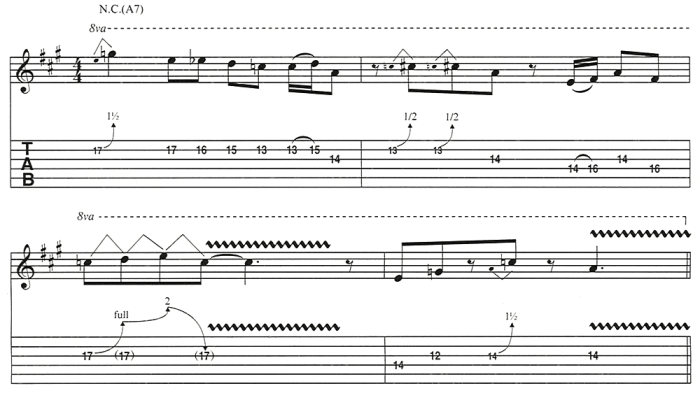

8. MELODIC BENDS

Players often bend only a few notes in a scale, and usually just a whole or half step, which can lead to unimaginative playing. Using bends of different distances will add fluidity and unpredictability to your phrases.

The A7 phrase in FIGURE 14 is based on a major pentatonic/blues hybrid scale and uses many different bends. In the first measure, the bend is one and half steps. In the second, it’s a half step, and in the third the C is bent two consecutive whole steps and then released the same distance. The fourth measure has another one-and-a-half-step bend.

FIGURE 14

Remember, too, that while many guitarists tend to bend on the highest, thinnest strings, bending on the lower strings can be an invaluable way to add variety.

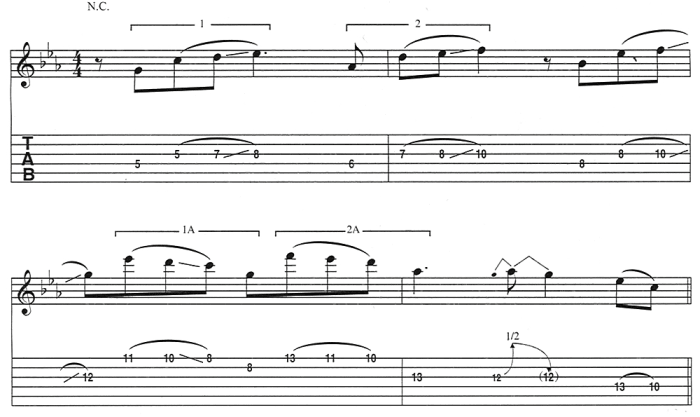

9. MELODIC SEQUENCES

Many great phrase are memorable because they’re built on a melodic sequence, an interval pattern that’s repeated at least once, usually on multiple pitch levels. Because these sequences involve repetition and variation, they can seem as if they’re carefully composed, like the melody of a song, and not just improvised.

FIGURE 15 contains two sequences and their inversions—notes played in the reverse order. Inverting a pattern you’ve already played is another way to give your lines a composed feel. The note group in bracket 1 (G C D Eb) reappears one octave higher in bracket 1A, but this time the order of the notes is inverted. The note in bracket 2A invert the nets in bracket 2 as well.

FIGURE 15

This figure features a linear scale pattern—a pattern that moves up or down, rather than across, the fingerboard and is played on a limited number of strings. Because it’s easy to use slides when you move these fingerings through each position, these kinds of scale patterns can give your playing a legato—that is, smooth and connected—feel.

10. MELODIC LINES OVER CHORD CHANGES

Playing one scale over a chord progression often works well, but learning to follow the progressions—to outline the chord changes with your solo lines—will bring an added level of melodic sophistication to your phrase.

One way you can start creating such line is by determining the half-step connections between the chords in a progression.

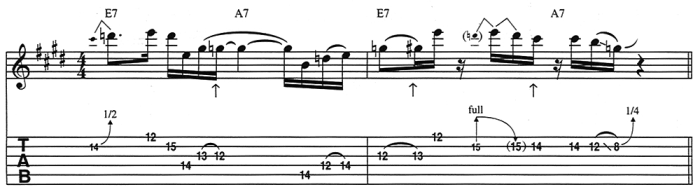

In FIGURE 16, we move between E7 (E G# B D) and A7 (A C# E G). These chords have two half-step connections: G# to G and D to C#. Often guitarists will play the second note of the connection on the downbeat. In this example, however, we either rhythmically anticipate or delay the chord change in our solo by playing the note before or after the hang actually occurs (the arrows indicate the anticipated or delayed chord notes).

FIGURE 16

Put these techniques to work in your solos, and see—and hear—the difference they make.

Guitar Player is the world’s most comprehensive, trusted and insightful guitar publication for passionate guitarists and active musicians of all ages. Guitar Player magazine is published 13 times a year in print and digital formats. The magazine was established in 1967 and is the world's oldest guitar magazine. When "Guitar Player Staff" is credited as the author, it's usually because more than one author on the team has created the story.