A Crash Course in Slash Chords

The Beatles, Led Zeppelin, Fleetwood Mac, Kansas and more have utilized slash chords to great effect - so why shouldn't you?

Back in the '80s, when I was a teenager struggling to master the endless enigma that is the guitar, I always looked forward to reading Rik Emmett’s “Back to Basics” column in these pages.

In addition to being the virtuoso singer and lead guitarist of the highly successful rock band Triumph, Emmett is also a great teacher who has a knack for explaining seemingly complex musical concepts in terms that are easy to grasp.

In an effort to emulate Emmett’s clarity, I try to present my own written and in-person guitar lessons in a way that removes any mystery or confusion.

One such topic that often seems to vex many of my beginner guitar students is the use of so-called slash chords, which are simply chords that have an alternate bass note or lowest note that is not the chord’s “normal” root note.

In the spirit of professor Emmett, I will attempt to demystify this topic here and offer examples of effective and highly appealing applications of slash chords in various musical contexts and styles.

Upping Your Game

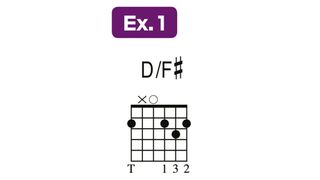

A slash chord is written with the chord followed by its accompanying bass note, with the two separated by a slash. For example, the D/F# chord shown in Ex. 1 is a D chord with an F# note on the bottom of the voicing, or “in the bass.” The standard way to refer to this chord verbally is “D over F#.”

Played by itself, D/F# sounds like a slightly less stable D chord, but when used as a passing chord in a progression, sandwiched between G and Em, it makes for a warm-sounding transition and a melodic bass line that moves in a smoothly linear, or step-wise, manner, as opposed to jumping up a 5th or down a 4th when changing from a G chord to D.

Play through Ex. 2 and notice how the low F# note makes for a bass line that “walks” down the G major scale (G, A, B, C, D, E, F#) from G to E then back up.

This smooth-moving “bass trick” has been employed in countless songs, such as Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Free Bird,” “Landslide” by Fleetwood Mac (with a capo at the 3rd fret) and, more recently, “Shallow,” as recorded by Lady Gaga and Bradley Cooper.

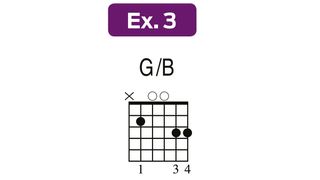

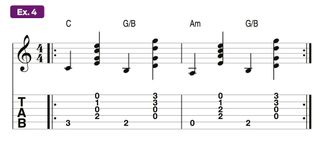

A similar step-wise bass line can be achieved by connecting the open chords C and Am with the transitional slash chord G/B (“G over B”).

Ex. 3 illustrates the G/B voicing, and Ex. 4 demonstrates this cool three-chord move, which Jimmy Page famously employed in Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven,” using flatpicked arpeggios, as did Lindsey Buckingham in the aforementioned “Landslide,” in this case with fingerpicking.

“Dust in the Wind” by Kansas offers another great example of this same C - G/B - Am move.

Now try plugging both the D/F# and G/B chords into the longer arpeggiated progression shown in Ex. 5.

Notice how, by strategically deploying both D and D/F#, as well as G and G/B, we are able to create a smooth, step-wise bass line that walks up the E natural minor scale (E, F#, G, A, B, C, D), which is made up of the same notes as the G major scale.

Slash and Burn

What do David Bowie’s “Space Oddity,” the Beatles’ “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” Led Zeppelin’s “Babe I’m Gonna Leave You” and Rooney’s “Blueside” have in common?

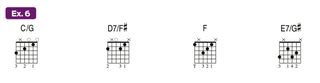

In addition to being classic songs, they all include a slash-chord-laced progression that starts on a minor chord and “drops” with a stepwise bass line that walks down to the “five” chord of the key.

Familiarize yourself with the chord grips illustrated in Ex. 6, and keep your 1st finger anchored on the C note on the B string’s 1st fret for the first four chords. To form the F grip, hook your thumb over the top side of the fretboard to grab the F bass note at the 1st fret.

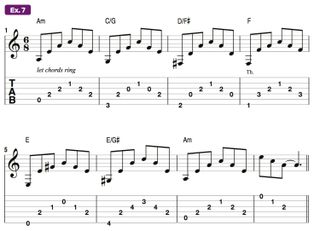

Then play through Ex. 7, which is my take on a fairly common but still eternally cool-sounding minor key progression that features arpeggiated chord voicings and an interesting, chromatically flavored bass “walk-down.”

R&D for Some R&B

In all the examples shown thus far, the alternate bass note in each slash chord was another chord tone besides the root - either its 3rd or 5th. In music theory, these are known as inversions, but that’s a discussion for another time.

Suffice to say here that, in addition to using these two alternate bass-note options, you can also use a non-chord tone in the bass, which can produce some magical sounds.

This “anything goes” slash chord approach is commonly found in jazz and R&B tunes. Ex. 8 lays out some lush-sounding, pianistic slash-chord voicings that are exploited for their sophisticated-sounding harmony in Ex. 9, especially when performed fingerstyle, with the thumb picking the bass notes and the index, middle and ring fingers plucking the chords.

The F#7sus4/C# and F#7/C can also be thought of as C#m7(add11) and C7(#11), but either way, they facilitate smooth chromatic downward movement in the bass. The A/B chord is essentially the IV (“four”) chord in the key of E major, A, with the 5th scale tone, B, in the bass.

A similar-sounding harmony can be heard in such songs as Stevie Wonder’s “Isn’t She Lovely?” and Justin Timberlake’s “Can’t Stop the Feeling.”

For a jazz-flavored resolution, I’ve lowered the top two voices of this chord a half-step each in bar 8, creating a B7b9 grip that elegantly and poignantly resolves to E6 in the final bar.

Pedal to the Metal

Flipping the previous idea of a smoothly walking bass line on its axis, Ex. 10 serves up moving triads (three-note chord voicings) played over a static (unchanging) bass note, which in this example is the open A string.

This kind of constant note played against a series of changing chords is known as a pedal tone, and its use offers a guaranteed way to build both musical tension and cohesion in a progression.

Play through Ex. 11 and notice the similarity to songs like “If” by Bread, “Ten Years Gone” by Led Zeppelin and the closing section of “Under the Bridge” by the Red Hot Chili Peppers.

It’s interesting to observe here that even though the pedal tone (the low A note) is not a chord tone in the Eadd9/A or G6/A chords, they don’t sound wrong or out of place in the context of the overall progression.

For our final example, kick on some metal-approved gain, add an alternate-picked palm-mute pattern to the open A-string pedal tone and punctuate it with the pared-down two-note chord voicings shown in Ex. 12.

This cool metal move brings to mind the driving riffs in songs like Ozzy Osbourne’s “Crazy Train” and “Bark at the Moon.” Whether you’re scaling up or down stepwise or just holding down the pedal, when it comes to slash chords, it’s “all about that bass,” as the song says. Now go put slash chords to work for you.

Get The Pick Newsletter

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!