How to Play Like Brian May

Our insider’s guide to emulating the unmistakable style of Queen’s legendary guitarist.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Dave Colquhoun has toured and recorded with a number of diverse artists, but one of the highlights of his career was working with Brian May for the 2018 Freddie Mercury biopic, Bohemian Rhapsody.

Colquhoun was responsible for coaching actors Gwilym Lee and Rami Malek to convincingly mimic May and Mercury’s guitar styles for the hugely successful film. Under the circumstances, it’s possible that, Brian May aside, no one knows the Queen guitarist’s stylistic idiosyncrasies better than Colquhoun. We asked him to share his insider tips to understanding and integrating May’s style into your playing.

Phrasing And Feel

Practice makes perfect in this vital area.

Brian May is a master of injecting his playing with feel, and in this regard at least, he’s up there with just about anyone who’s ever picked up the instrument. Phrasing and feel are fundamental facets of his style that, as Colquhoun stresses, take technique and skill to accommodate.

“The most important thing to do is switch the phrasing around,” Colquhoun explains. “If you take the ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ solo apart, you’ve got what I refer to as an ‘acceleration’ when it runs between 16ths and triplets and then back again [from 2:44–2:47]. It makes you play the same pattern; you just change the note grouping of it.

“It’s actually a simple concept, but it can be tricky, as you’re always looking for the downbeat, so just try repeating the pattern in 16ths and in triplets. It’s challenging to slow down to go out of a triplet back to a 16th note, but just learn to phrase and you can bend and hang onto a note to give yourself time to think.

"I try to imagine it while I perform it, and somehow my hand makes that sound. But as always, it’s all about effective practice.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Best example: “Love of My Life” (A Night at the Opera, 1975) 2:18–3:00

Soloing With Melody

Always apply melody and space to solos.

“May’s solos are among rock’s finest, and he’ll always construct them around a melody so that they properly serve the song. An interesting thing with Queen recordings is that it’s almost as if the solo is a complementary piece within the song,” Colquhoun observes.

“If you look at ‘Somebody to Love,’ the guitar is given a lot of space, and when it’s featured, it becomes the focus of the song. Afterward, it pretty much disappears from the mix altogether. When Brian is given a moment to shine, he’s given the space in which to do it. Yes, it’s a solo, but then it’s also like a separate piece of music sitting within the song.”

Best example: “Somebody to Love” (A Day at the Races, 1976) 2:01–2:22

Finger Vibrato

A fundamental part of any player’s technique.

May’s elegant vibrato is unmistakable, and it’s a cornerstone of his playing that he adjusts to fit the differing styles, tempos, and vibes of the songs and guitar lines with which he’s made his name.

“The main thing is to be able to bend up to a note and vibrato just under the pitch you’ve bent to, then drop down and back up again,” Colquhoun explains. "Try not to ever let it go sharp.

“I think it’s really important to play standing up, as hand position is critical. So my two tips in this area are to practice standing and to tune into the tempo of the vibrato, as it obviously needs to be different for ‘Hammer to Fall’ compared to, say, ‘These Are the Days of Our Lives.’”

Best example: “Killer Queen” (Sheer Heart Attack, 1974) 1:40–2:00

Guitar Vibrato

How to add vibrato to chords to aid the guitar’s musicality.

If you watch May perform, you’ll notice that his right hand rarely strays from the guitar’s vibrato arm. He’ll often have his fingers and palm wrapped around it close to where it meets the bridge and manipulate it to slightly move the tuning when playing chords.

This allows the guitar to fit in more musically with the rest of the band. A light touch is required, and the technique is simple to re-create with versions of Fender’s Synchronized tremolo, a Bigsby or, as long as you’re careful, a double-locking system.

Best example: “One Vision” (Queen – Live at Wembley, 1986)

Picking Dynamics

How using a coin as a pick can add texture and color.

Another intrinsic part of May’s tone is his use of an English sixpence as a pick. He likes the intimate connection its inflexibility gives, and he will either delicately stroke the strings to give a metallic character to the sound or minutely alter the angle of his hand to dig the coin’s serrated edge into the strings, resulting in a more aggressive and gnarly tone.

There’s a great example of the latter technique at 0:42 during the song “Death on Two Legs.” Sixpences aren’t too difficult to find online, but if locating a stash of these old U.K. coins proves difficult, try using the slightly smaller and thinner U.S. dime.

Best example: “It’s Late” (News of the World, 1977) 0:00–0:15

Cleaning Up

Every guitar has a volume control. Use it.

When a clean tone is required, May will reach for the guitar’s volume knob. His amps are always run flat out, and he’s never used any type of channel switching, so it’s up to him to manipulate the pot to quickly go from full-throated overdrive to lilting clean.

“It’s just the way that it goes from distorted to totally clean, and it sounds like he’s changed the amp,” Colquhoun says.

“The volume Brian plays at is pretty intimidating, and just touching the guitar like he does, stroking the strings and coaxing sounds out of it, makes you realize how good he is at being so sensitive with it. Practice with some amount of volume if you can, although I’m sure your neighbors won’t love me for saying that.”

Best example: “Spread Your Wings” (Live Killers, 1979) 0:53–1:07

Bending

Practice bends to add some vital emotion.

May uses light strings and a very low action, so he needs to be in full control when bending up to a note.

“If you’re practicing bends, you need to consider which string it is that you’re bending and where on that string you are,” Colquhoun advises. “I’d suggest that the easiest place to practice and learn control is on the G, somewhere from the middle of the string length to about the 12th fret.

“Of course, as you get closer to the bridge or the nut, the tension changes significantly, so although you’re trying to reach the same pitch, you’re going to have to apply a different amount of pressure to get the same result, depending on where you’re bending from.

"With the high E, you need an awful lot of pressure. You’re trying to achieve the same sound across all the strings, wherever you are on the neck.

“For practice, play over a drone of whatever note you choose and then try to get the pitch exactly the same as you bend up from different parts of the string. You’re trying to make musical dissonance between where you’re bending from and how long it takes that bend to get up to the note.

"Another great way to practice is to bend to the note as a pre-bend and then listen to where your pitch is when you get to it. That will teach you about the pressure required.”

Best example: “We Are the Champions” (News of the World, 1977) 2:40–2:58

Use Your Index Finger

A signature pick-hand technique to add expression.

When May needs a softer sound, he’ll sometimes palm the sixpence and use his index finger to entice notes from the string. It’s a subtle, yet very effective way of adding dynamics and expression for heartbreaking emotion.

“I asked Brian about this,” Colquhoun says. “He explained that he does it to get direct contact with the string. He said he was picking along the length of the string, so it’s almost like he was stroking it.

"What I took from that was, when you normally pick a note, it will initially go sharp until it starts to settle again, but if you pick it more gently and along the length of the string it will stay at pitch. So if you pick it really gently, you’re almost fine tuning it, and it’ll be very sweet sounding.”

Best example: “Bohemian Rhapsody” (A Night at the Opera, 1975) 5:33–end

Know Your Legato

A well-used part of the tonal arsenal.

Legato is an essential technique for smooth and swift lead work, and Brian has often used it combined with alternate picking and a hybrid of tapping and string bending.

“Brian is predominantly a legato player, so any hammering-on needs to be smooth,” Colquhoun explains. “Use the weight of your hand rather than thinking of it as being just your finger that’s hitting the string. Use it for a musical reason, and think about where the accent is within the beat, too.

“I’ll play the same patterns and look for the offbeat or downbeat. Then the battle is to make the hammered-on notes as loud as the picked notes. You’ve got to increase the intensity of the hammer-on, then lower the volume of the picked notes. Again, it’s about control.”

Best example: “It’s Late” (News of the World, 1977) 3:33–3:49

Taming Feedback

How to make your feedback sound musical.

The Red Special’s semi-acoustic construction and colossal neck, not to mention the sheer volume at which Brian runs his amps, means that he has a surprisingly musical feedback on tap.

“It’s about proximity, but it’s not easy at domestic volumes,” Colquhoun observes. “As a place to start, if you point the guitar at the amp, there will be a spot where it takes off somewhere, but you’ve got to walk around the room until you get it to feed back.

"It’s so much a part of Brian’s sound, but it’s not a distortion sustain; it’s more like a feedback that’s always there. With Brian’s style, it’s more about stopping the feedback than trying to get it when you want it.”

Best example: “We Will Rock You” (News of the World, 1977) 1:21–1:32

Finding Harmony

Wonderful harmonies are a Queen signature.

“Bohemian Rhapsody” is of course the ultimate illustration of how Queen skillfully multitracked vocals to stunning effect, and Brian always applied many of the same recording techniques for his unique and staggeringly inventive guitar orchestrations.

When tackling the daunting task of re-creating such musical confections, consider the full chords that underpin the core melody you’ve come up with, and then experiment with inversions and finger positions to identify effective harmonies.

Build the chords with one note per track and try to ensure that the harmonies entwine rather than simply follow each other up and down in step. Be warned: This is a highly technical and laborious process that will make you wonder how Queen managed to do any of it in the pre-digital era.

Best example: “All Dead, All Dead” (News of the World, 1977) 1:42–2:13

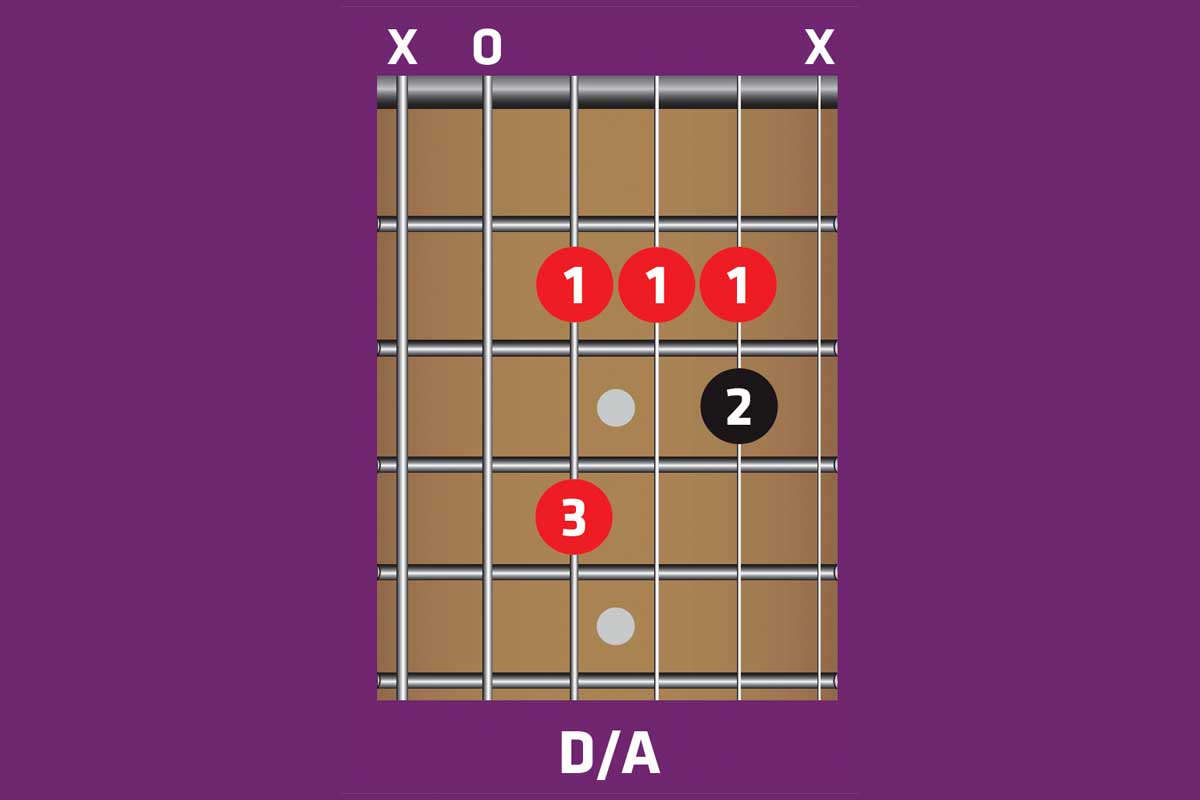

Learn The D/A Chord

Simple, but effective.

One of May’s anchors is D/A, where he plays the notes of a D chord over the open A string. He’s used it on countless occasions in both solo passages (“We Will Rock You” and “A Kind of Magic”) and rhythm sections (“Put Out the Fire” and “One Vision”).

“Hammer to Fall,” a true go-ahead rocker, is built upon D/A, and it’s a chord that’s essential to nailing May’s playing style.

Best example: “Hammer to Fall” (The Works, 1984) 0:00–0:07 and throughout