How to Master John Frusciante‘s Irresistible Funk Grooves

Learn Frusciante’s exemplary rhythm-playing approaches on the Red Hot Chili Peppers classic, 'Blood Sugar Sex Magik.'

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

On September 24, 1991, three albums were released that would go on to change my world. Two were from bands out of Seattle, and the third from Los Angeles. Care to guess which albums?

Here are some hints: Both bands from Seattle named their albums with words spliced together to form one perplexing title.

One was a colloquialism that a youthful grunge culture with no spellcheck at the ready blindly accepted, while the other was a snarky play on words meant to scoff at a Montrose song. The L.A.-based band named theirs with not a care in the world for syntax or for spelling all the words properly.

Despite all three bands disregarding the written word, this trifecta would go on to sell in the millions, define a generation, and basically change everything for everyone. Give up? It was Nirvana’s Nevermind, Soundgarden’s Badmotorfinger, and the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ Blood Sugar Sex Magik.

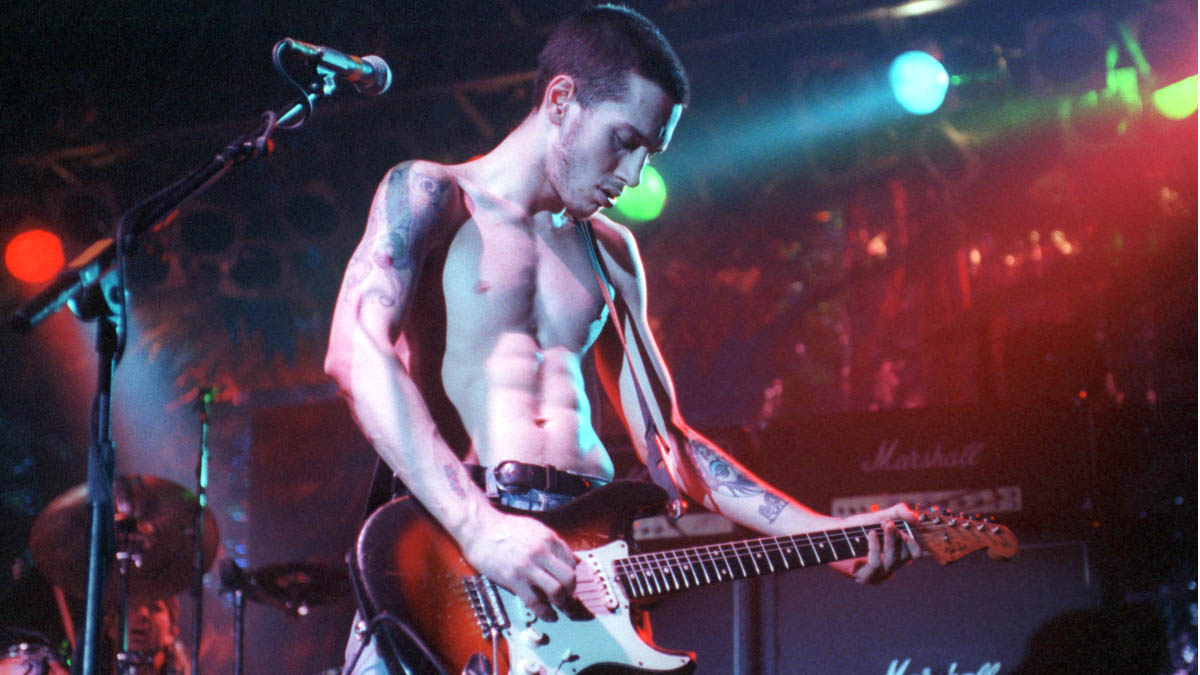

For me, the latter’s impact was so great that it altered my own artistic trajectory almost overnight and set me on a path that I still enthusiastically follow nearly 30 years later. This is due, in large part, to the fearless playing and composing of a then 21-year-old guitarist named John Frusciante in his first tenure with the Peppers.

Together with his bandmates – vocalist Anthony Kiedis, drummer Chad Smith, and bassist Flea – and lauded über-producer Rick Rubin, Frusciante created this seminal suite of well-written songs that featured some of the phattest and funkiest riffs and grooves ever.

Armed with vintage Fender Strats and Jaguars, mythic Marshall amps, such as the 100-watt Super Bass and the beefy 200-watt Major heads, and an array of scrappy pedals, including a Boss DS-1, an Ibanez WH-10 wah, and a pivotal Boss CE-1 analog chorus, Frusciante wrote the manual for ’90s funk guitar that still invaluably informs today’s players.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Blood Sugar Sex Magik is not only the album that made the RHCPs superstars, it’s also the one that made every aspiring rock and pop guitarist (including yours truly) grab a Strat, take an ad out in a local music rag, and start a funk band.

Whether you had an established connection to funk music or you were a clean slate, after hearing Blood Sugar Sex Magik you were hooked and wanted to sound like it. In this lesson, I’m going to show you what I did to do just that.

To wrap my head and hands around any new style, I examine its best practitioners by studying and learning an entire record.

Whatever sticks I then morph, or “recompose,” into my own. The examples throughout this lesson follow that ethos and highlight the essential concepts I gleaned from Frusciante’s stellar work throughout Blood Sugar Sex Magik.

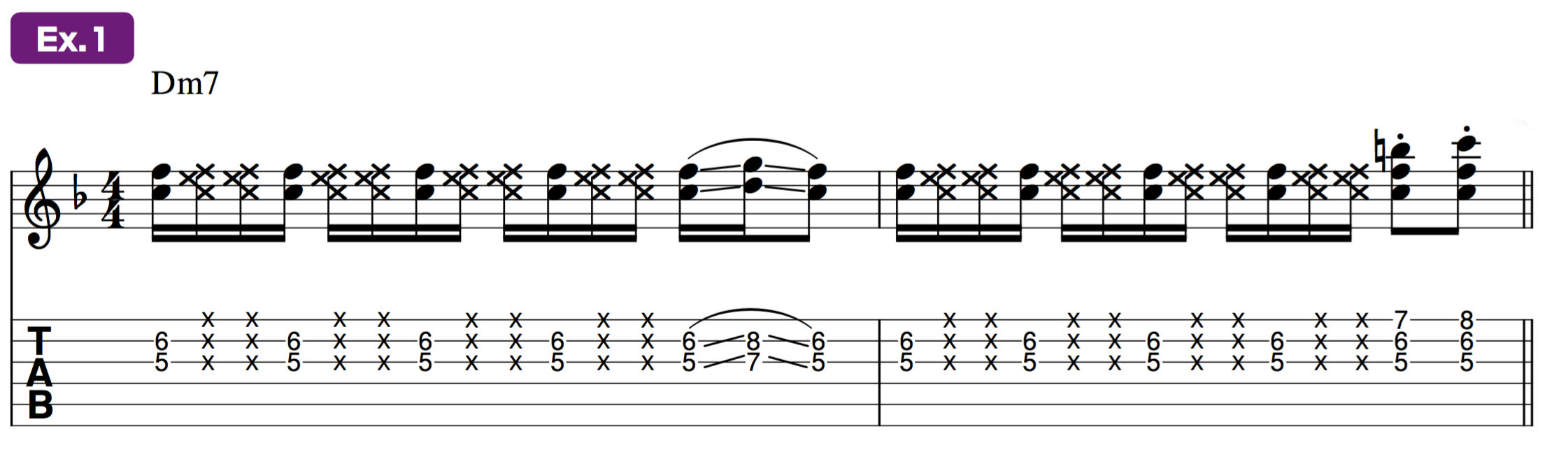

Starting it off is a look at his clever uses of 4th intervals, or 4ths, for short. Example 1 is a riff in D minor not unlike the intro from “If You Have to Ask.”

Making use primarily of a perfect 4th (C-F) on the G and B strings, this two-bar vamp rocks to a foundational 16th-note polyrhythm featuring percussive, fret-hand-muted “scratch” strums. Indicated by Xs in the notation, those pitchless scratches are achieved by loosening your fret-hand’s grips on the strings while still lightly touching them as you strum with the pick.

To play this figure without any unwanted string noise creeping in, try fingering the C-F dyad with the tips of your 2nd and 3rd fingers while your 1st finger lightly lays across the top three strings. For the final two chords in bar 2, shift your hand so that your 1st finger frets the G string at the 5th fret and the rest will fall into place.

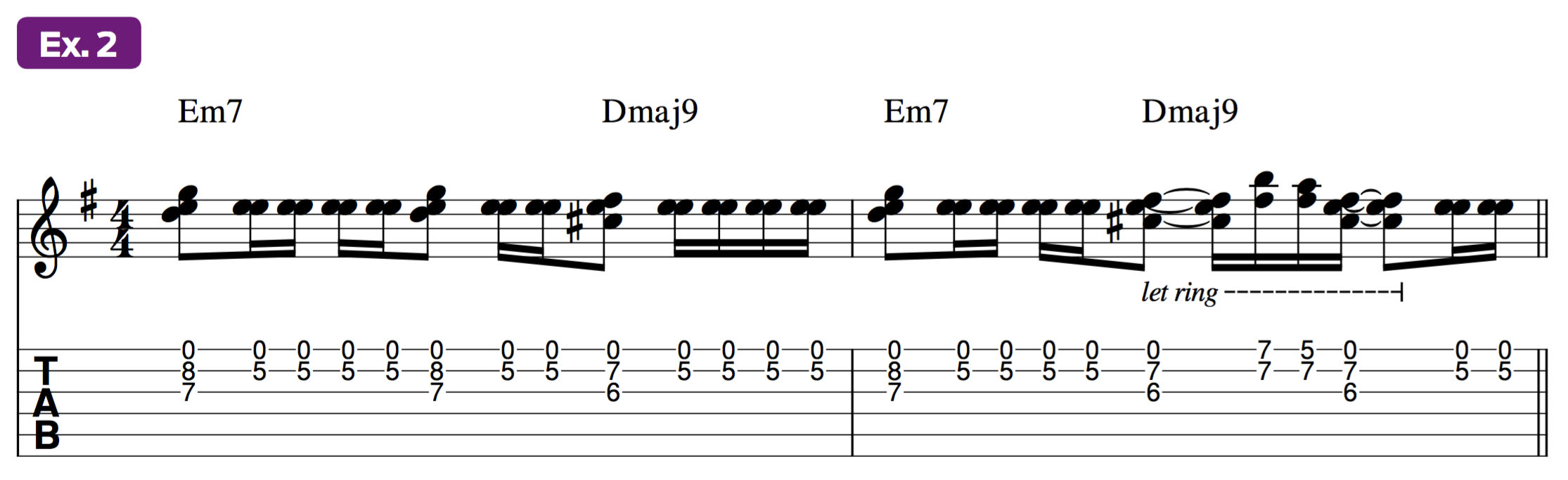

Inspired by the open high-E-string idea that Frusciante employed in the intro and verses of “The Power of Equality,” Example 2 incorporates additional harmony (Dmaj9).

In this example, the initial perfect 4th (D-G) should be fretted with your 3rd and 4th fingers, with the 1st finger then reaching back to grab the 5th-fret E note on the B string. In the Dmaj9 chord, switch to the fingering scheme from Ex. 1 for the fretted C# and F# notes (2nd and 3rd fingers).

This will set you up nicely for the melodic movement on top of the chord during beat 3 of bar 2. At all times, be careful not to arch your 1st finger so that you don’t inadvertently dampen the open high-E string.

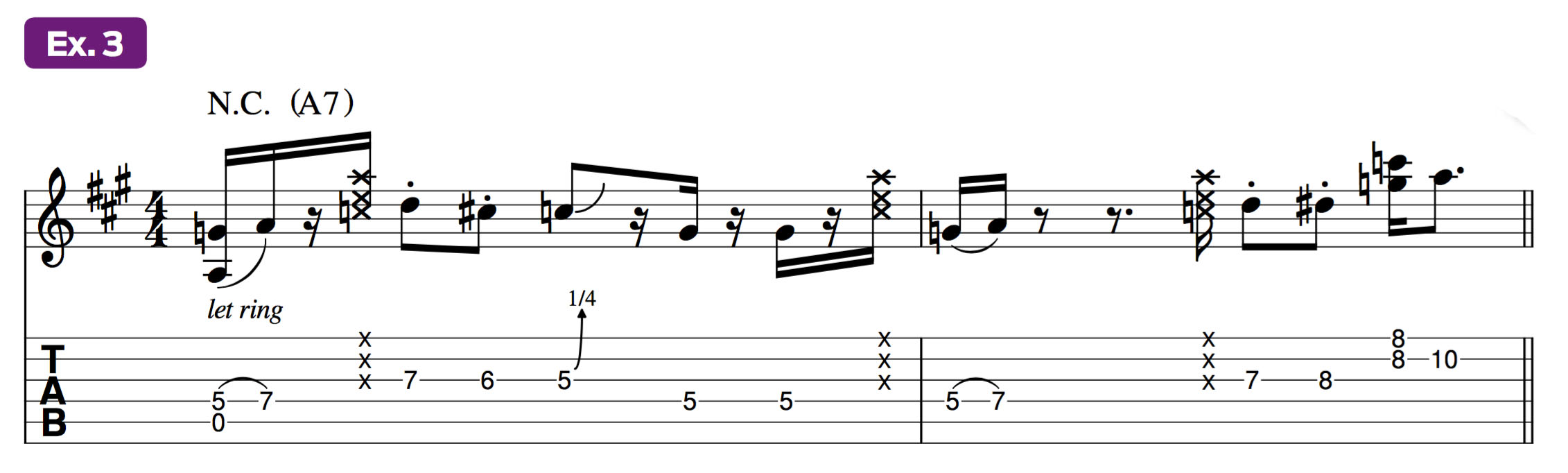

Frusciante is a master of crafting irresistibly catchy single-note melodic verse riffs that sit perfectly behind vocals, as epitomized by the chart-topping single “Give It Away.”

Example 3 similarly travels from 5th to 8th positions as it juxtaposes major and minor tonalities. Like Frusciante, use an aggressive pick attack to coax the most tone from each note, and don’t overlook the quarter-step pull-bend inflection applied to the 5th-fret C note on beat 3 in bar 1.

Using these subtle bends, also known as “curls,” is a staple phrasing technique that Frusciante liberally employs in his playing.

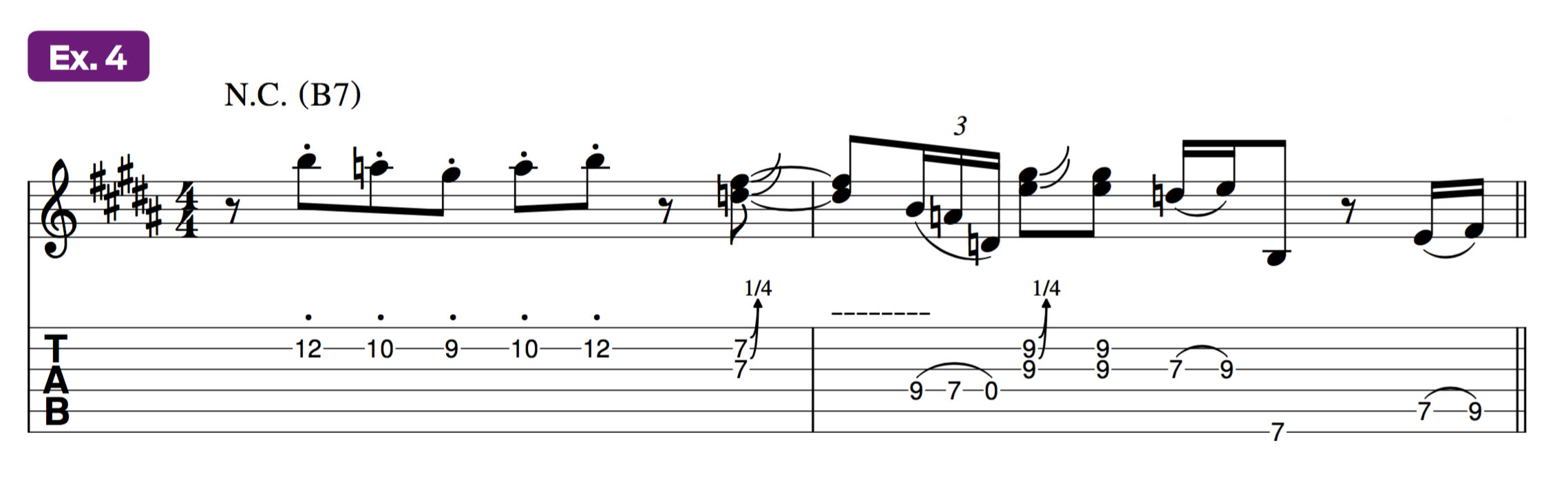

Example 4 offers more single notes and curls with our first mash-up, which is inspired by elements from the verse riff to “Mellowship Slinky in B Major” and the intro to “Funky Monks.”

Our original offering starts with a staccato lick on the upbeat of beat 1. To get more snap in your pick attack, try pinching the B string between your pick and whichever finger you use to hold it against your thumb.

Be mindful not to overbend the double-stops at the 7th and 9th frets beyond a half step; keep them closer to a quarter-step curl. It takes only a slight pull-down to get the intended effect.

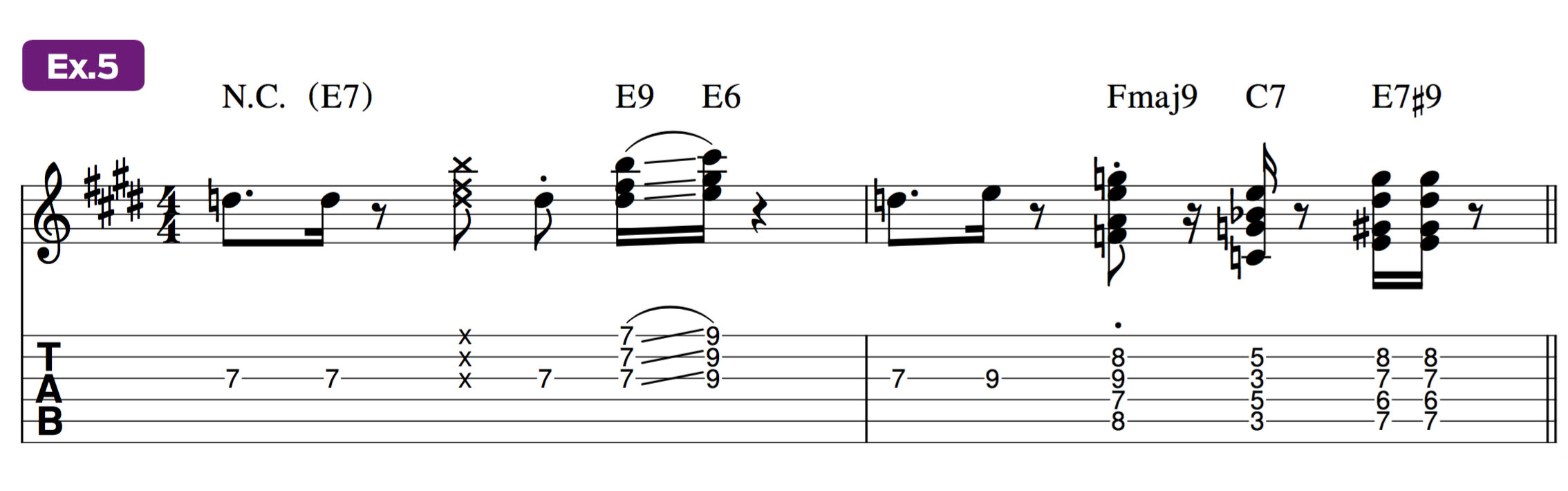

Shifting gears to a harmonic approach, Example 5 mashes together ideas inspired by the intro to “Apache Rose Peacock” and the chord interlude in “If You Have to Ask.”

As you play through bar 1, use only your 1st finger to fret both the single notes and to perform the sliding three-string barre across the top three strings, which, by the way, creates an upper-structure harmony move that’s sometimes referred to as the “6-9 slide,” even though you’re moving from a dominant 9th chord to a major 6th. (“6-9” just rolls off the tongue better than “9-6.”)

For the more robust middle-string voicings of Fmaj9, C7, and E7#9 in bar 2, you’ll need to employ a few more digits. A tone as exposed and up-front as Frusciante’s leaves no room to hide, so for the best chance at clean chord changes, try forming their shapes, or grips, in the air before clamping the fingers down onto the strings.

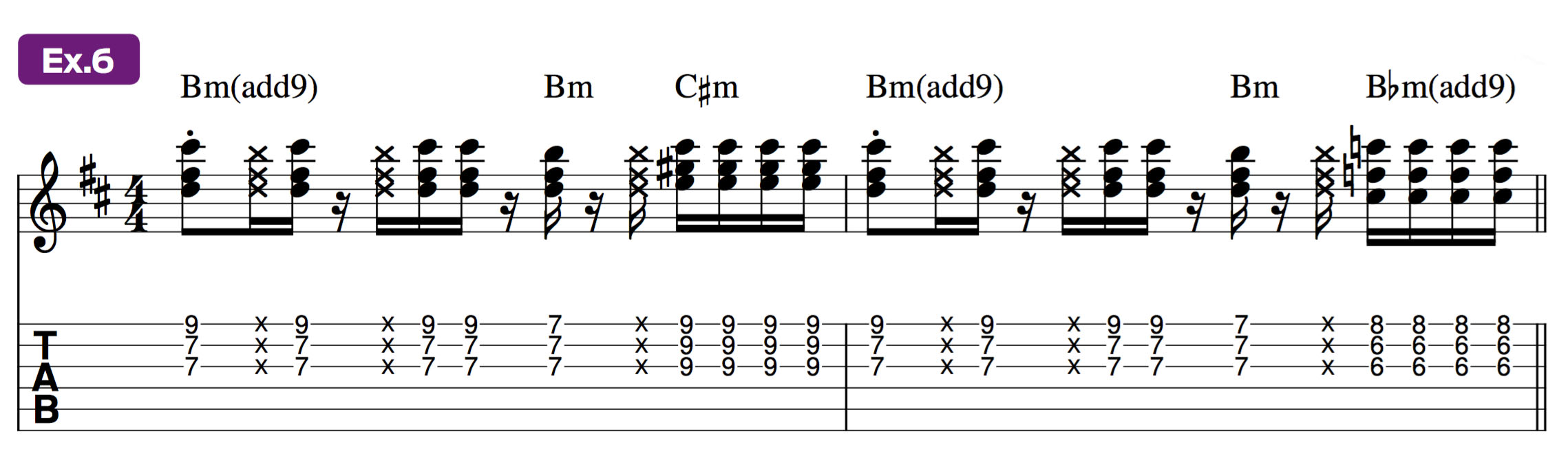

Examples 6 and 7 demonstrate Frusciante's penchant for using barred double- and triple-stops on the treble strings.

Example 6 is informed by the “Mellowship” chorus groove while at times incorporating a minor add9 sound by raising the note on the 1st string a whole step (two frets) above the barre. You can hear these same kinds of voicings in the intro riff and chorus sections in “Naked in the Rain.”

While this two-bar groove doesn’t have you playing consistent 16th notes like Ex. 1, it’s still to your advantage to have your strumming strokes follow a constant 16th-note motion, which some call 16th-note pendulum strumming, and apply the downstroke or upstroke attacks to the strings when needed.

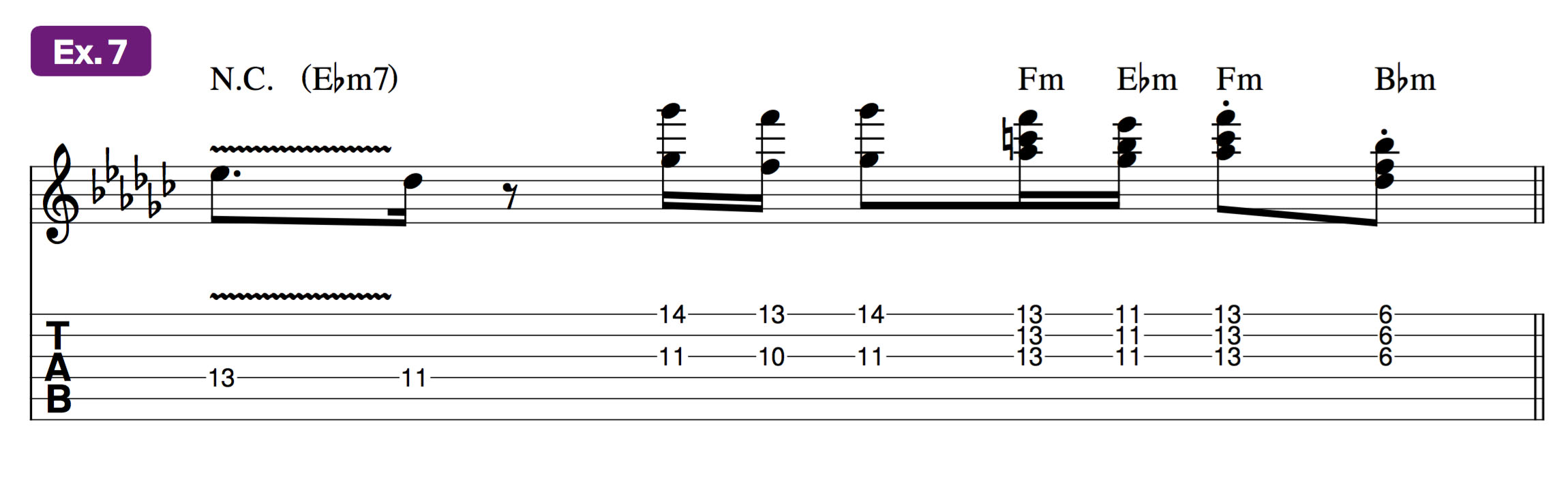

Example 7 takes inspiration from the interlude in “The Power of Equality.” For the ricochet action between the 13th- and 11th-fret barres, use your fret hand’s 3rd and 1st fingers, respectively.

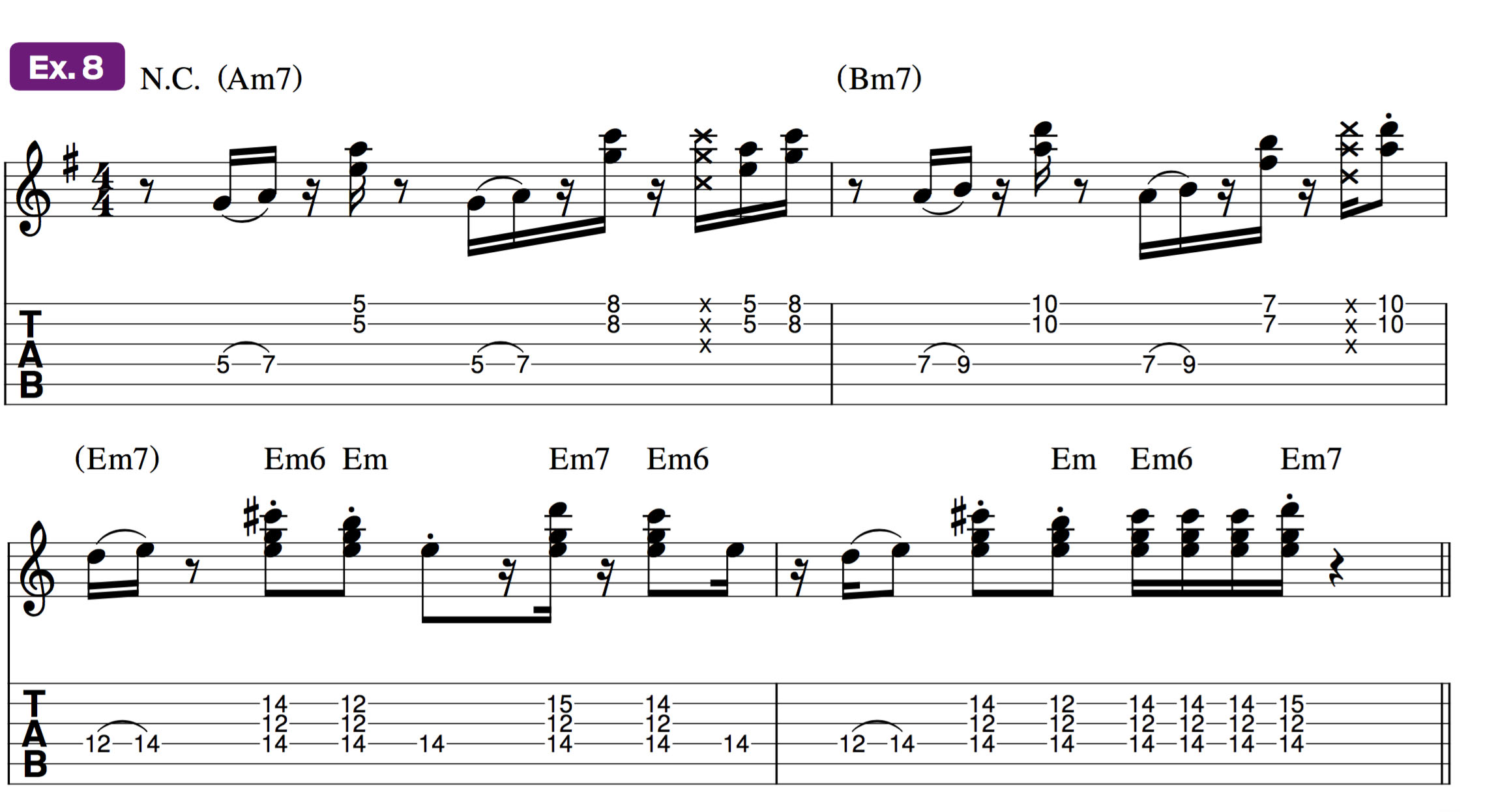

Frusciante’s chorus riff writing is another brilliant aspect of his musicality. My personal favorite is the deep pocket heard in “My Lovely Man,” an homage to fallen founding RHCP guitarist Hillel Slovak, whom Frusciante credits as his main source of inspiration and guidance when he was first getting his own funk chops together.

Example 8 captures the spirit of the iv-v-i changes (Am7 - Bm7 - Em7) in the chorus. Note the use of eighth and 16th rests on several of the downbeats in bars 1 and 2, as well as the jumps from the whole-step hammer-ons on the 4th string to the perfect-4th dyads on the top two strings.

Although in this song Frusciante played his finishing touches in Em in 7th position, I shifted the idea up to 12th position and added an additional lower E root note on the D string’s 14th fret, much like “Catfish” Collins did on funk standards such as “Soul Power” and “Flashlight.”

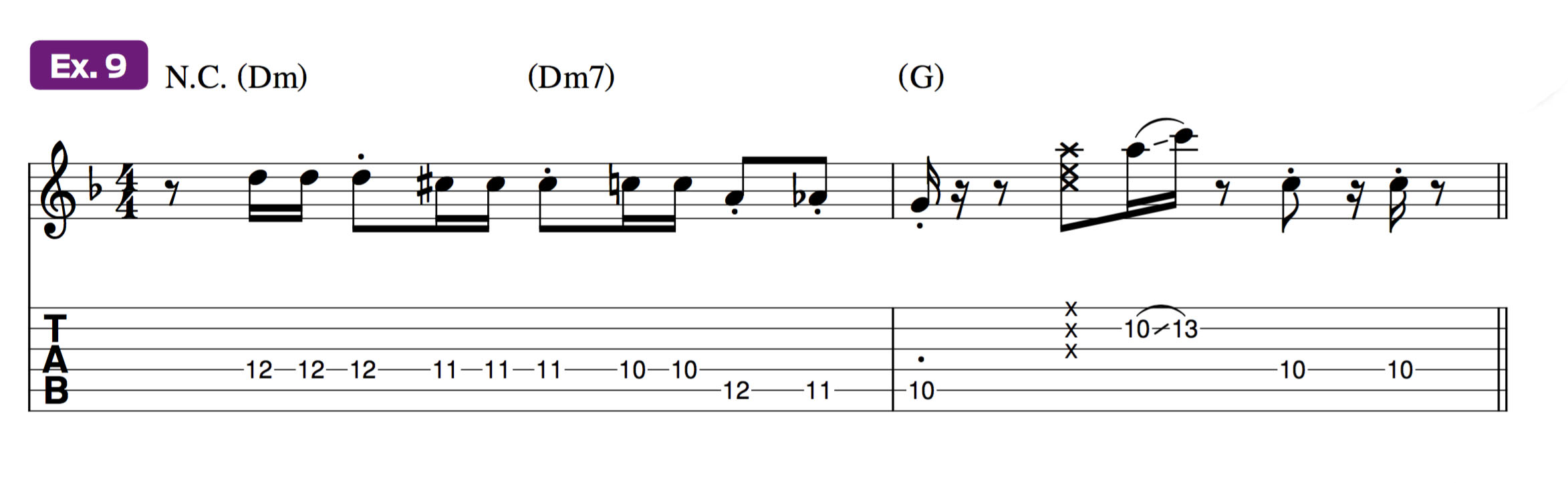

Once more resting on the downbeat, Example 9 chromatically descends a Dm riff starting on the root, much like Frusciante does in the chorus riff in “Power of Equality,” before it switches to a more minimalist approach in bar 2, reminiscent of “If You Have to Ask.”

For extra “stink,” be sure to nail the staccato phrasing throughout bar 1 and keep it clean as you play the syncopated 10th-fret C notes (the b7) in bar 2 following the slinky three-fret slide from A (the 5th) to C.

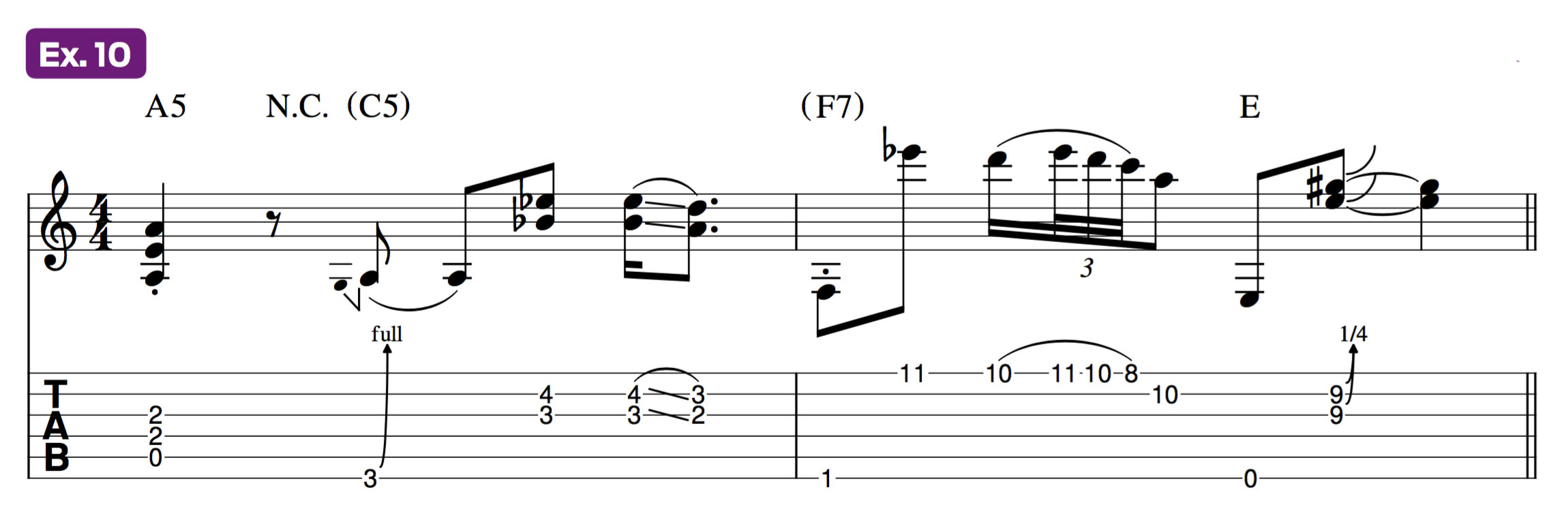

Example 10 offers another example of Frusciante's super-catchy and grooving chorus riff-writing style, with a concentrated approach inspired by his phrasing in “Funky Monks.”

Bar 1 is close to the original idea, with an added pull-down bend on the low-E string borrowed from “The Greeting Song.” Bar 2, however, takes John’s riff and displaces it up an octave while maintaining the pitch range of the low-F and low-E root notes.

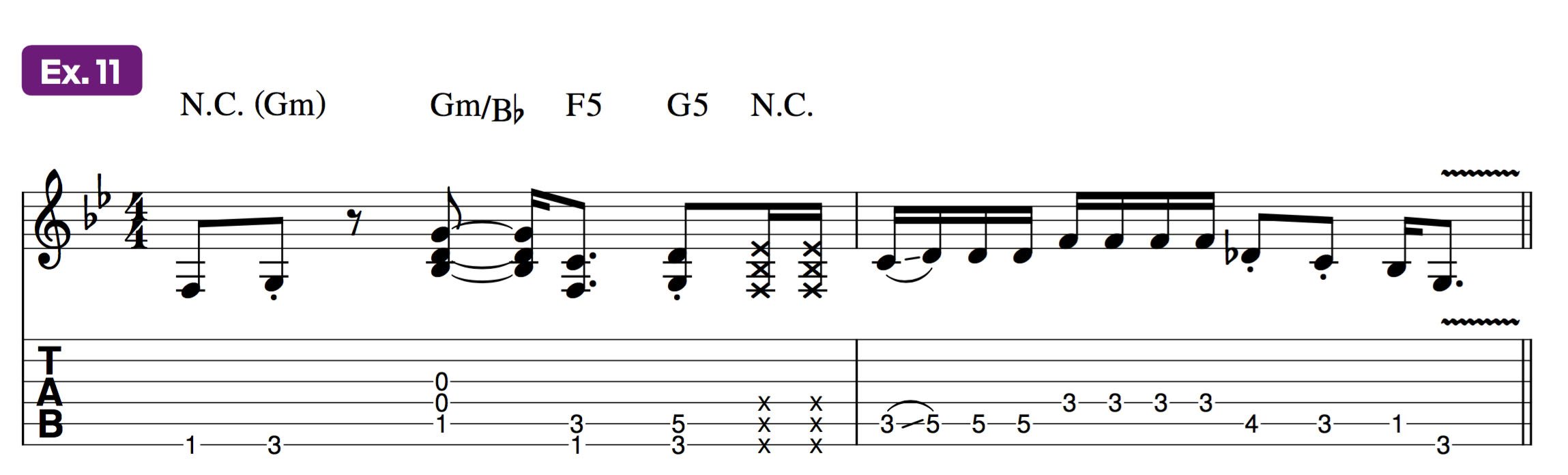

Stepping away from riffs that serve verse and chorus sections, Example 11 offers up a brawny mash-up riff in G minor that’s a condensed amalgamation of the “Suck My Kiss” and “Funky Monks” intro figures.

As you’ve come to know, a consistent ingredient in Frusciante’s secret musical sauce is the use of staccato (short and crisp) articulations and phrasing throughout.

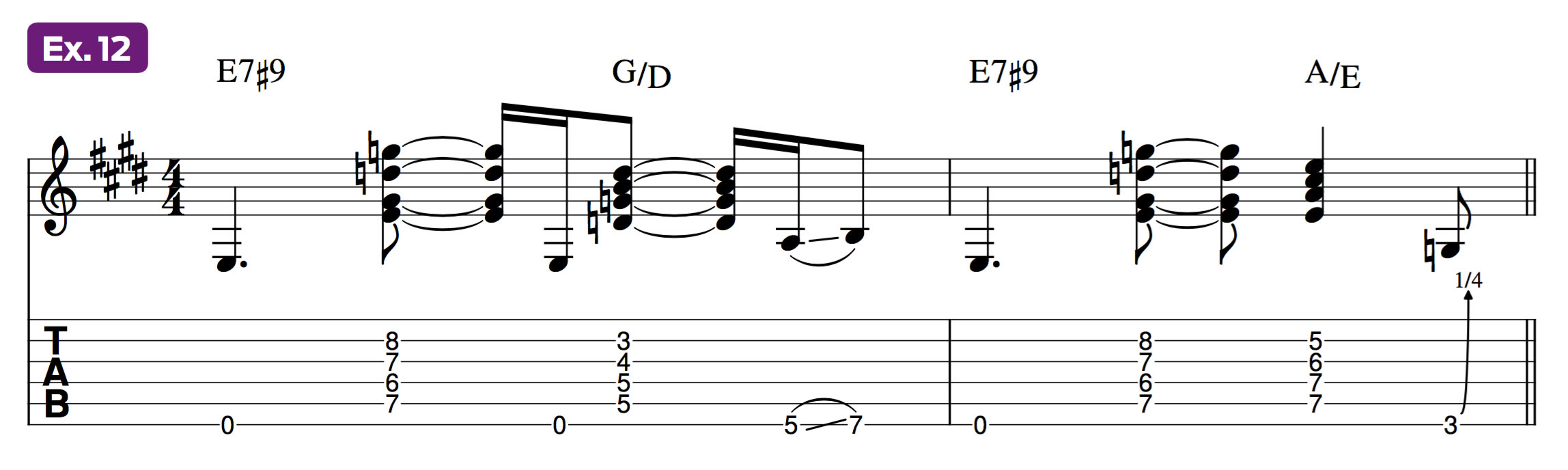

Taking a cue from the mammoth, yet carefully spaced outro riff from “Apache Rose Peacock,” Example 12 strategically applies a couple of Frusciante’s go-to chord voicings on the middle four strings for E7#9 and the 2nd-inversion major chords G/D and A/E.

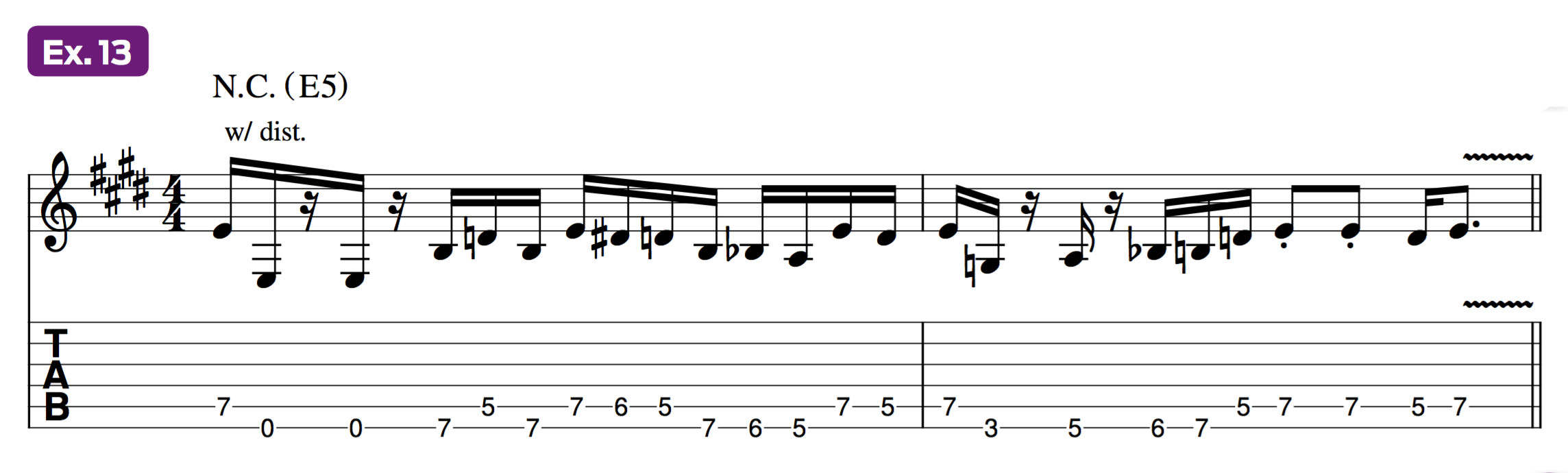

Applying Frusciante-style tight 16th-note syncopations to a single-note line, Example 13 twists the intro riff to “Mellowship” into a Hendrix-like vibe on the bottom two strings. The influence of both Hendrix and Curtis Mayfield is undoubtedly heard in John’s rhythm work. Consider his playing throughout the breakout single “Under the Bridge.”

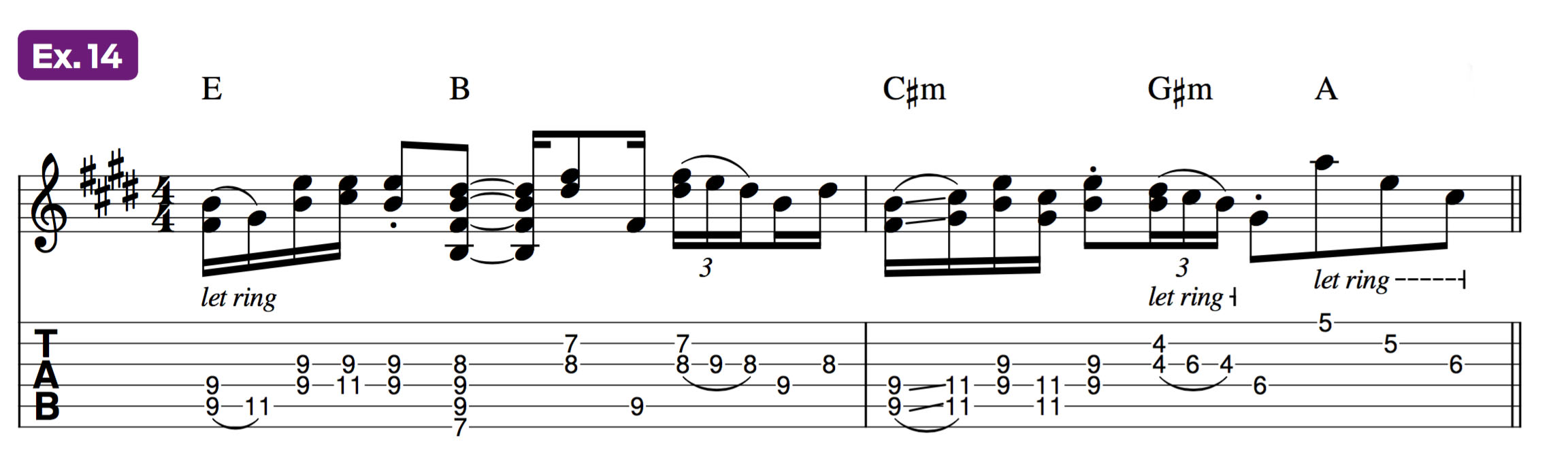

In Example 14, a similarly styled approach is shown, demonstrating that time-tested style of clean-electric chordal embellishment, with tastefully soulful, decorative hammer-ons and pull-offs to “chordal extensions” nested within larger common barre chord shapes.

Example 15 takes you on an eight-bar journey reminiscent of the outro section of “Sir Psycho Sexy.” Throughout this jam, you’ll find defining Hendrix-style elements, such as the clearly stated major or minor chord or root of the implied chord at the start of bars 1–7.

In addition to the nested, ringing legato embellishments throughout, oblique, pedal steel–style bends are featured in bars 1–4, which bring to mind Hendrix's classic riffing in his solo in “Little Wing.” Finally, regarding the mash-up elements, look for added expanded motives from Frusciante’s own trick bag that we’ve presented in this lesson.

Hopefully, playing these recomposed renditions of John Frusciante’s rhythm guitar creations featured on Blood Sugar Sex Magik will inspire you to do the same on your own. While it’s a challenging journey, it’s also one that’s fun and potentially very rewarding. Keep the funk alive!

Chris Buono is a top-selling TrueFire Artist with nearly 50 instructional videos, and a featured instructor on guitarinstructor.com. Bookending his years as a Berklee professor, he authored eight books, including the popular Guitarist’s Guide to Music Reading and his most recent publication, How to Play Outside Guitar Licks.