A Crash Course in the Texas-Sized Melodic Phrasing of Billy Gibbons

A comprehensive look at the smooth signature fretboard navigation techniques of ZZ Top's guitar great.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A number of things come to mind when you think of Texas – rolling cattle ranches, vast oil fields, and porterhouse steaks the size of a Cadillac. But for many guitarists and music fans, a mention of the Lone Star State recalls another vision that includes seminal classic rock legends ZZ Top.

For over five decades, this easily recognizable trio has left its lasting mark on blues-based rock, led by a bona fide six-string legend, the exceptionally talented and stylish Billy Gibbons, a.k.a. Reverend Willy G.

The bearded guitarist has quite the musical legacy. His earliest influence was watching blues icon B.B. King perform live at ACA Studios (where Billy’s father worked) when Gibbons was eight years old.

From that moment on, he found himself obsessed with King’s music and playing style. But he also harnessed additional inspiration from other blues legends, such as Lightnin’ Hopkins, Jimmy Reed, and Muddy Waters.

As Gibbons began to forge his own guitar style in the late ’60s, he became an avid admirer of Jimi Hendrix’s playing and eventually met the iconic rock legend backstage in 1969, around the time ZZ Top was formed.

Beginning with the band’s inspired 1971 debut album, ZZ Top’s First Album, the power trio blazed a musical trail through the ’70s and ’80s with its signature stripped-down but fat-sounding blues-rock style and have enjoyed continued success and immense popularity ever since.

As a testament to their fame and influence, ZZ Top were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2004 and in 2019 celebrated their 50th anniversary as a band.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Gibbons is a walking blues encyclopedia and has a strong connection to the emotive phrasing characterized by his influences’ playing styles. He also generates plenty of “handling noise” when he plays, such as his trademark use of pinch harmonics – also known as pick harmonics and “squealers” – which gives his licks a strong sense of personality and character.

Another interesting facet of Gibbons’ lead guitar style – which is the primary focus of this lesson – is his smooth and deft use of finger slides to seamlessly shift positions, a technique that enables him to rove and roam over a sprawling expanse of the fretboard and craft flowing phrases up and down the neck.

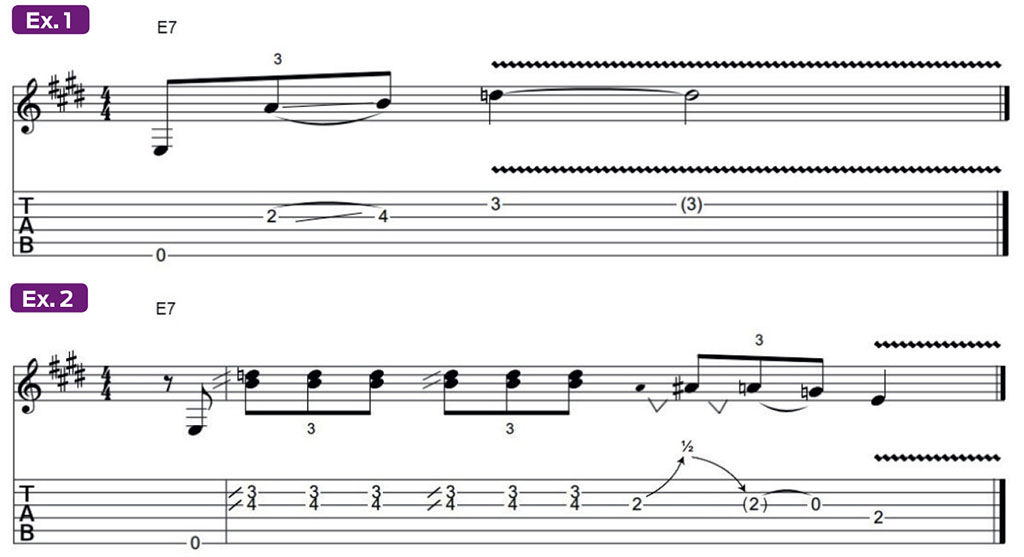

To get things started, Example 1 presents a four-note glissando finger-slide motif heard in plenty of guitar-driven blues songs. This simple E7-based phrase can be found in such classic recordings as “Boom Boom” by John Lee Hooker, and you can also find variations of this slippery-sounding lick lurking in famous rock songs, such as “Young Lust” by Pink Floyd.

As you play through the phrase, notice the slide up to the fifth of E (B) before targeting the minor, or “flatted,” seventh (D), on the B string, which is held and shaken with some hearty finger vibrato.

This basic arrangement of notes is begging to be played over an E7 chord, so practice it a few times to get a feel for this simple yet effective and authentic blues lick, then start putting it to use in your own soloing endeavors.

Example 2 includes a variation on the previous phrase and is inspired by Gibbons’ playing in the intro to “Bedroom Thang." The key technique here is to pluck the double-stop notes on the G and B strings at the same time, either fingerstyle or with the pick and your middle finger, before ending the phrase with the open-position bend and pull-off lick.

You can trace this type of aggressive double-stop playing to blues legends such as Elmore James, along with a rock version of the phrase featured in the classic Creedence Clearwater Revival song “Green River."

Once you’re comfortable playing this double-stop based phrase, you can recycle and repurpose the fingering scheme and shift the shape up and down the fretboard. Relocating the fingering will expand what we’ve targeted on the neck to other musical applications and produce a number of locations that you can explore using the same shape.

Example 3 showcases a number of different areas where you can deploy this fingering, and as you ascend the B string, notice that you’re eventually targeting four of the five notes of the E minor pentatonic scale (E, G, A, B, D).

Also notice the range of parallel tonalities (based on the same root note) that are unlocked by moving the shape up the neck. The first shift produces an E7 sound (E, G#, B, D), while the second implies the E major pentatonic scale (E, F#, G#, B, C#) and an E6 chord (E, G#, B, C#), both of which were among B.B. King’s favorite musical flavors.

The third phrase creates a distinct Em7 tonality (E, G, B, D), while the final idea outlines an E major triad (E, G#, B). The assortment of implied tonalities offered by this movable shape can help you craft a variety of cool licks and phrases all over the neck.

To help you visualize the areas of the fretboard that we’re touching upon here, check out Figure 1, which presents a birds-eye view of the shapes that we’re traversing and targeting.

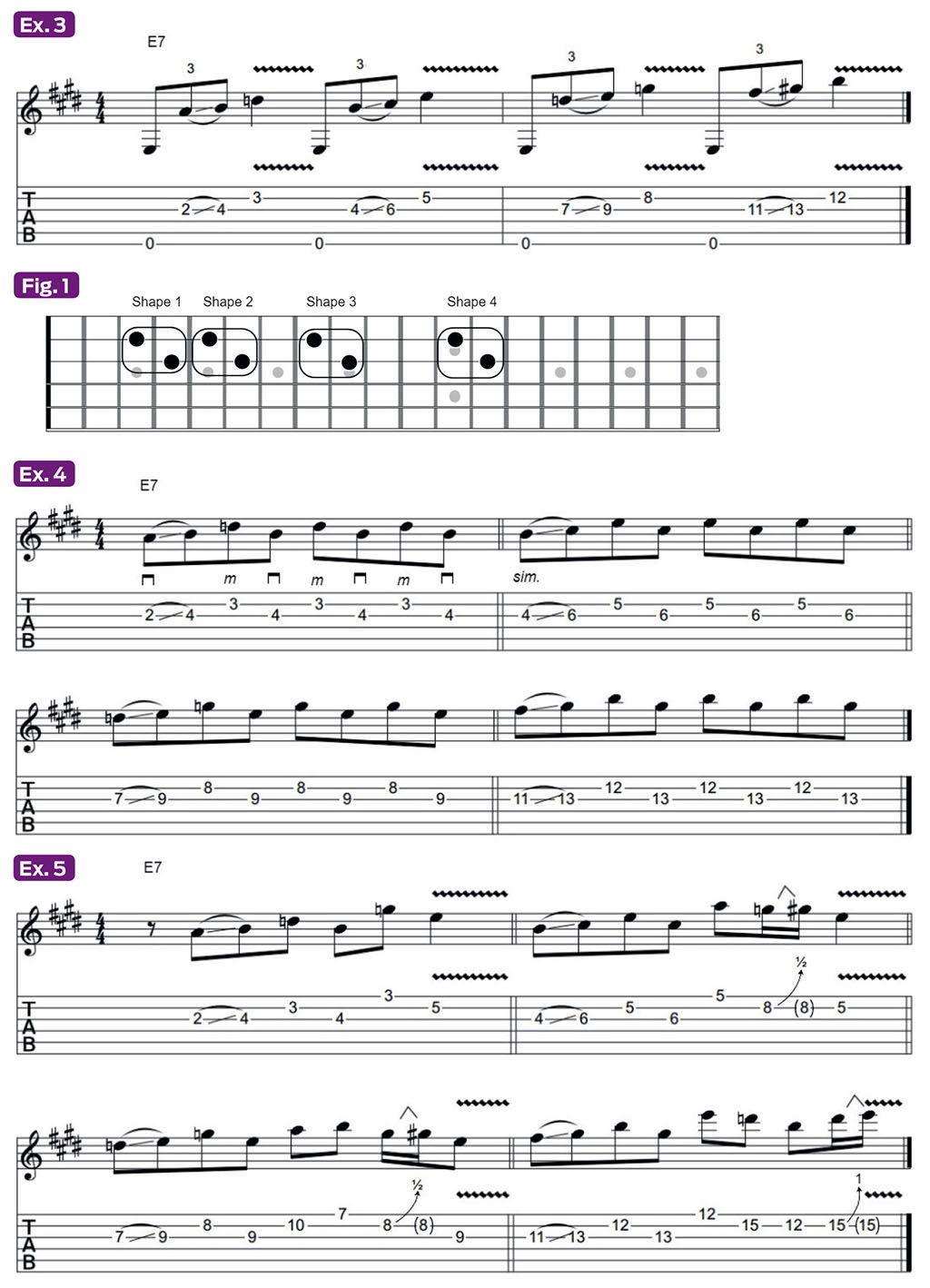

Example 4 demonstrates a signature element of Gibbons’ lead playing, the accented application of hybrid picking (pick-and-fingers technique), and features a series of phrases that outline the four fretboard positions we targeted in the previous example.

As you play through these four bars, notice how much easier it is to quickly toggle back and forth between the G and B strings by plucking the B-string notes with your pick hand’s middle finger, as opposed to trying to sound all the notes with just the pick alone, which would require a lot more movement and effort.

The musical effect created here by the rapid alternation between the two notes played a minor third apart on adjacent strings is akin to licks one would typically hear a blues harp (harmonica) player or organist play.

You can distinctly hear Gibbons employing hybrid picking in this manner in several ZZ Top classics, such as “La Grange," “Brown Sugar,” and “Sharp Dressed Man."

Example 5 expands upon this concept with an assortment of bluesy licks that use this fretboard shape as a movable template, in each case with the E root note falling under a different fingertip.

This approach of targeting a specific area on the fretboard and building licks around a repurposed movable shape is common in blues guitar playing, and it is also employed widely in rock, jazz, metal, country, and bluegrass.

The next section of our lesson takes this fretboard shifting concept and applies it to the E minor pentatonic scale (E, G, A, B, D), which is a staple in Gibbons’ musical vocabulary and blues-rock in general.

Example 6 illustrates three interconnected one-octave E minor pentatonic shapes that move diagonally up and across the fretboard, via finger slides and position shifts.

Gibbons often employs this extended diagonal fretboard “path” to traverse the neck and visit different positions when soloing, and learning it will provide you with a highly useful tool for navigating the neck and breaking out of a single “box” pattern and position.

To help you memorize this three-octave shape, study the illustration in Figure 2, which will give you a visual image and “road map” of it.

Once you’ve familiarized yourself with these three interconnected, overlapping shapes, experiment with shifting and sliding your way through them, as demonstrated in Example 7.

Notice how much expression and soulfulness the legato finger slides add to the phrasing here. Gibbons has made this technique a key factor in his playing for decades, and you can hear similar slides in such ZZ Top classics as “Cheap Sunglasses” and “I’m Bad, I’m Nationwide," to name a couple.

Example 8 presents this same interconnected E minor pentatonic path, or “superhighway,” as a continuous ascending run.

As you practice these extended-range sliding and shifting movements, notice the milestone octave connections occurring on the fretboard as we’re combining the three individual one-octave shapes into a single, seamless three-octave pattern. Be sure to practice descending through the pattern as well.

Once you’ve become familiar with the overall shape in this key – which, by the way, can be either E minor or G major, as E minor pentatonic and G major pentatonic share all of the same notes – try transposing the entire template to other keys and fretboard positions by moving every note up by the same number of frets.

For additional reference and direction using this pentatonic superhighway concept, you can hear other guitar legends navigating it in their music, such as Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, Eddie Van Halen, and Stevie Ray Vaughan, to name a few.

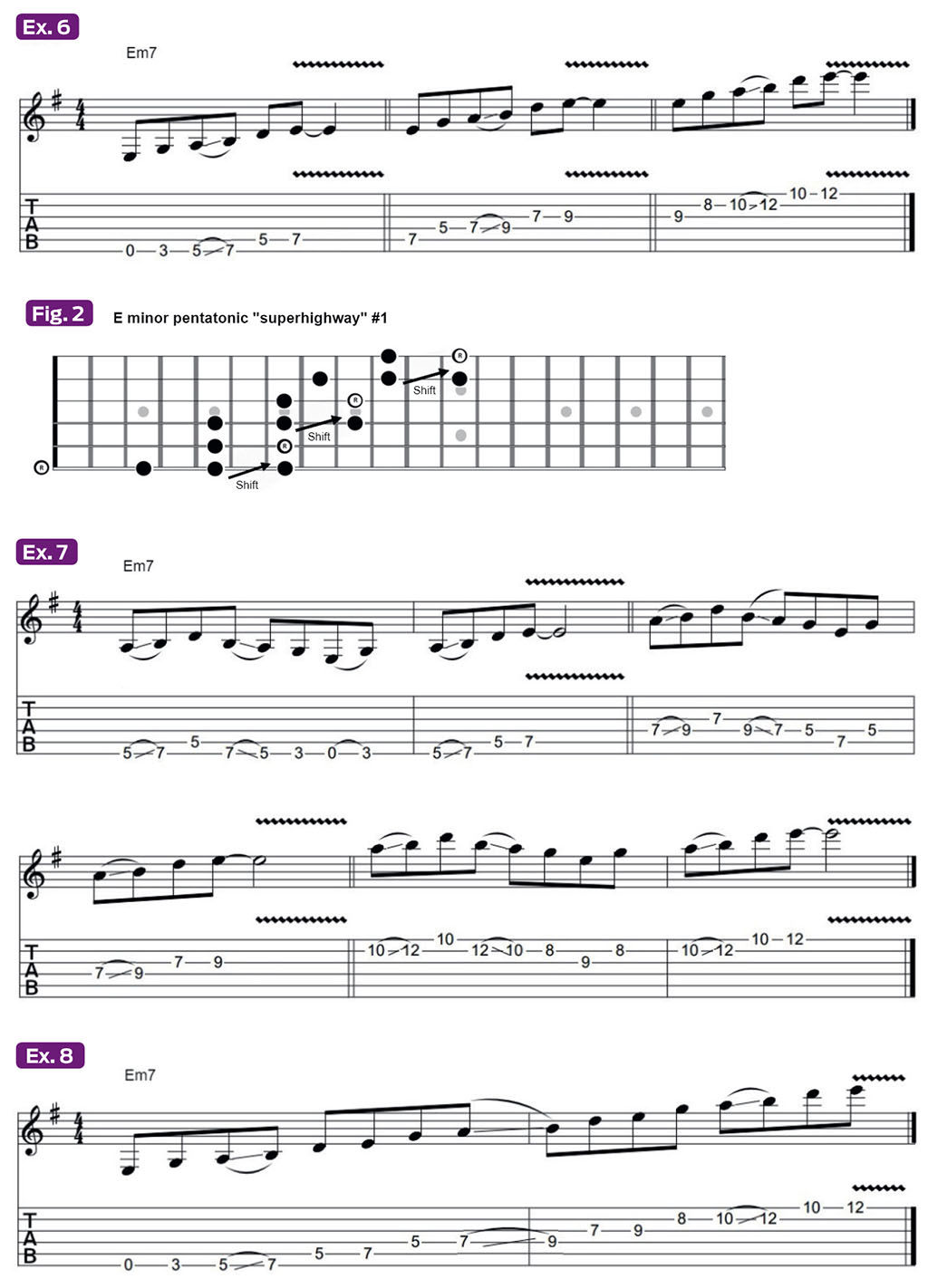

Our next example, Example 9, presents a descending run that visually and melodically cascades “down the mountain” and our E minor pentatonic superhighway, from the 12th-fret “peak” on the high E spring to the open low E.

This example should serve as a good template for helping you create your own original extended-range licks and navigate the fretboard effectively, by combining neighboring shapes and positions and making seamless octave connections.

Example 10 and Figure 3 present another very important and useful three-octave pentatonic pattern, located further up the fretboard and in a higher register.

Like the previous extended pattern, this one, which we’ll call “E minor pentatonic superhighway #2,” works equally well for G major pentatonic, connects segments of neighboring pentatonic box shapes, and allows you to access additional positions with ease, utilizing finger slides.

Gibbons has employed this pattern in various keys in his licks and improvisations, great examples being in his solos in “La Grange” and “Cheap Sunglasses,” both in the key of C minor, for which he employs this same visual pattern shifted down four frets, to C minor pentatonic (C, Eb, F, G, Bb).

Practice ascending and descending this fretboard path repeatedly. Once you have it visualized and under your fingers, check out the descending run shown in Example 11, which incorporates pull-offs and downward finger slides, techniques that will enable you to smoothly zigzag through this arrangement of notes.

This type of phrasing and articulation will also help you become more adept at inter-positional navigation.

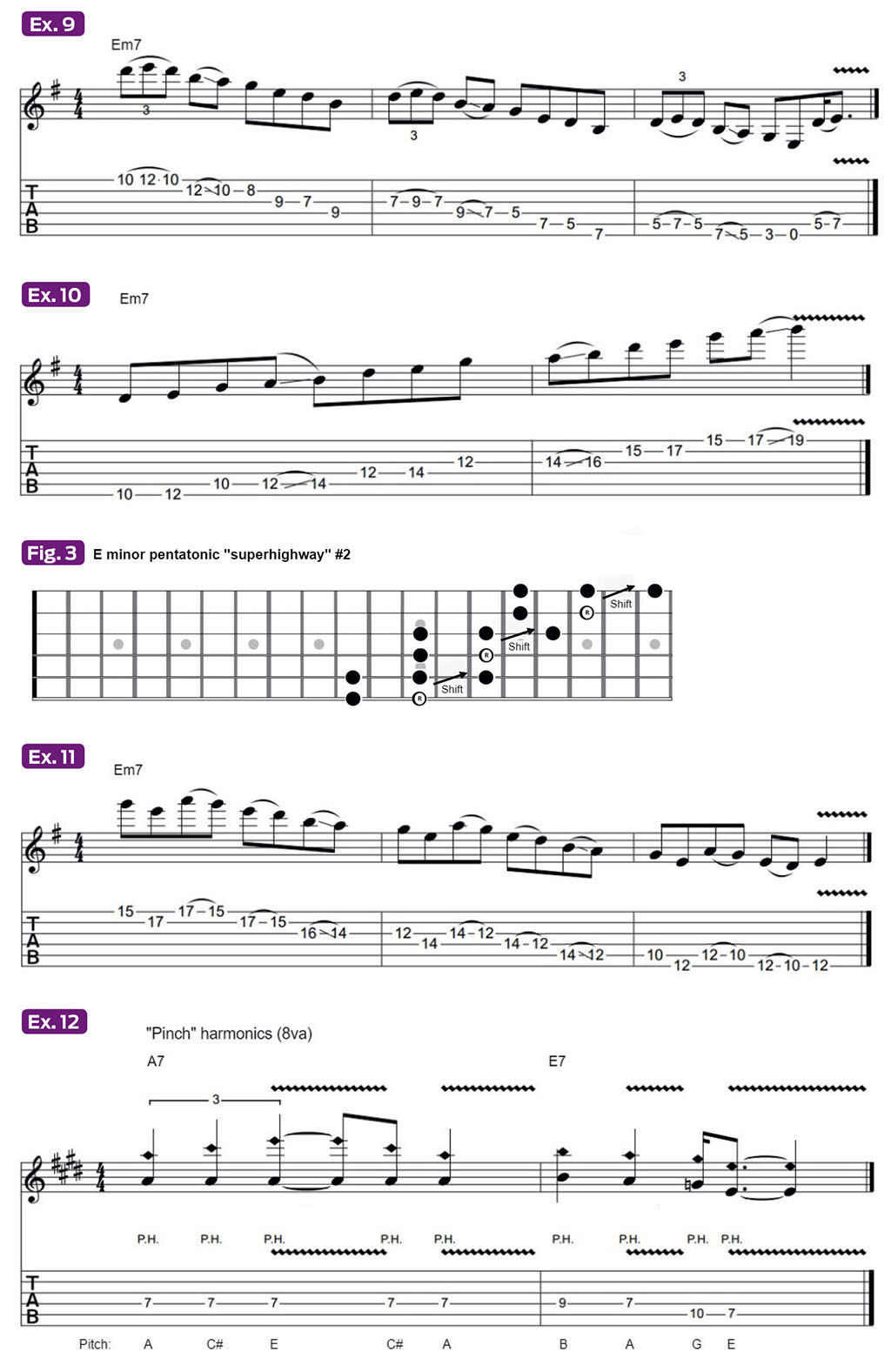

Of course, no lesson on Billy Gibbon’s guitar style would be complete without a look at his celebrated use of pinch harmonics.

Indicated by the abbreviation “P.H.” in sheet music and tablature, a pinch harmonic is produced by down-picking either an open or fretted note (the latter is more common) while simultaneously touching, or grazing, the string with the side of your pick-hand thumb.

But in order for a harmonic to sound, the thumb needs to touch the string precisely at one of several specific points along its length, which are called nodes, several of which are located in the area over an electric guitar’s pickups.

The harmonics produced with this technique are typically one or two octaves higher than the fundamental (the open or fretted note) and sometimes an additional major third or perfect fifth (comparable to natural harmonics).

Inspired by Gibbons’ soulful, tone-driven soloing style, Example 12 offers a demonstration of pinch harmonics with a short, E minor-pentatonic-based phrase played in the middle area of the fretboard over the chords A7 and E7 (the IV and I chords in the key of E).

Notice that the first five notes are a succession of different harmonics, all generated from the same fretted A note at the D string’s 7th fret.

The variety of harmonic pitches are achieved by “pinching” the string at different node points, the locations of which differ for each fretted note on a given string, so you’ll need to find those “sweet spots” by hunting and pecking in the area over the pickups.

As is always the case with harmonics, using your guitar’s bridge pickup and a good amount of overdrive/distortion will help bring out the sound of pinch harmonics. Standout examples of Gibbons using this technique to great effect in his solos can be found “La Grange,” “Cheap Sunglasses,” “Legs,” and “Rough Boy."

Gibbons learned his way around the fretboard and developed his style by borrowing and emulating playing ideas and concepts gleaned from his musical influences and peers, and by following his own creativity and imagination. Don’t be afraid to break out of the box and try blazing new fretboard paths. You never know what kinds of cool sounds you can tap into by moving sideways.